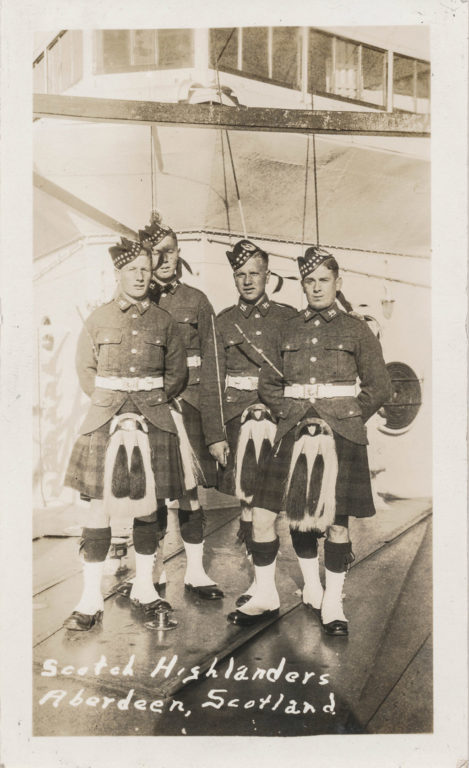

An unknown vintage photograph of highland soldiers.

Do you have a plaid coat?

What about a plaid shirt? Plaid dress? Plaid skirt?

If you do, you share something in common with both Madonna and a man living three thousand years ago in western China. You might also be arrested for wearing it, should you find yourself in the wrong place and wrong time in history.

Plaid (or tartan) is one of the most widespread and popular fabrics of all time, arguably because of its simplicity of production and ease in which meaning can be applied to its design. With the basic change of a few thread colors, a nearly infinite number of patterns are possible. Think for a moment about all the associations you have with plaid. It can represent both a preppy jock and a salt-of-the-earth working man. It can mean private school, and it can mean underground punk. It can mean Burberry, and it can mean Pendleton.

Like one of its colored threads, we can trace the story of tartan with remarkable constancy from before the dawn of modern times, following it as it weaves a path through human history. It is a manifestation of the stubborn human desire to create beauty where none is required; for the maker to leave his or her mark; and, from a Scottish warrior to an Iron Age farmer to an angry teen in 1970s New York City, to be able to say, “I belong.”

What is plaid, and what is tartan?

Tartan is defined as a pattern created by crisscrossing horizontal and vertical colored bands, achieved by weaving pre-dyed threads of varying colors in specific repetitive sequences. The sequence of threads is called a sett; setts either reverse and repeat (symmetrical) or just repeat (asymmetrical). Plaid actually comes from the Gaelic word “plaide,” meaning blanket, and originally referred to a garment.

This garment was made for the highlands, and the Scottish highlands are a harsh place. The air is damp and heavy with bone-chilling humidity, born on the relentless fogs that roll in from the North Sea. It takes sturdy people to thrive in such a place. It also takes wool.

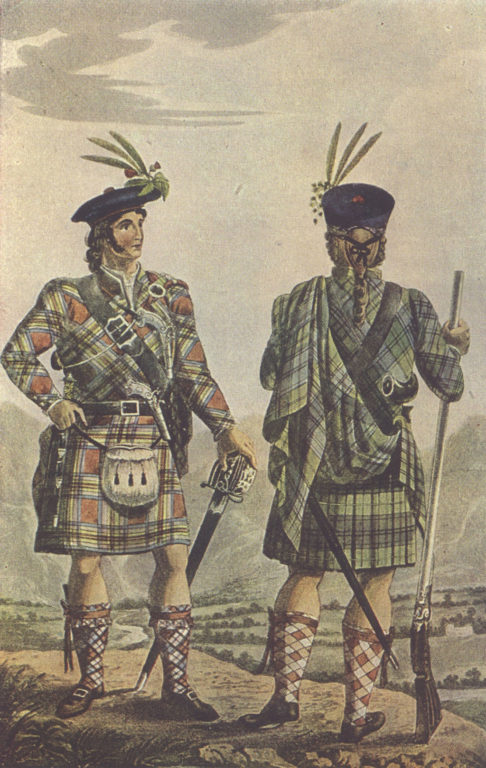

A depiction of Scottish soldiers from 1630.

Stretching back into the dim light of the Middle Ages, nearly every Scotsman wore a wool plaid. A plaid was essentially a large blanket—usually patterned with a tartan design—belted around the waist. The wearer would spread the plaid on the ground, fold it into pleats, then lay down and roll himself up in it. The extra was tossed over the shoulder, often pinned in place with a brooch. The plaid is not like the small kilts we are familiar with today (by comparison, those are practically miniskirts) but was instead a piece of fabric large enough to use as blanket, shelter, or whatever else necessary when the situation called for it.

Over time and across different regions, the word plaid eventually came to mean not only the garment, but its pattern as well. That is why those words today can be synonymous. But despite being heavily associated with Scotland in both pop culture and pop history, tartan actually has a much more distant and ancient origin than the kilted men of the Highlands.

Ancient Origins

The Tarim Basin in far western China is a remote, inhospitable environment of shifting sand and arid scrubland. It is still only mainly accessible via death-defying transport in small aircraft. The Silk Road is used to brave these stretches of desert, crisscrossing carefully from oasis to oasis to traverse its expanses, but not much else has thrived.

Its conditions may have made the Tarim Basin a hostile place for life, but they are ideal for one thing: the preservation of death. In the last century or so, hundreds of incredibly well-preserved mummies known as the Ürümchi mummies have been found in the Tarim basin. Some of them are thousands of years old, and they have provided an unexpected twist in the history of ancient China. Many are tall, with Caucasoid features and red hair. And one of the many strange things about the mummies is the fabric and clothing accompanying them.

Fabric, in general, is extremely perishable. Its fragile natural fibers mean it is one of the first things to rot, disintegrate, or at the very least lose most of its color. Very few ancient textiles have survived to modern day, making the study and documentation of fabric history quite difficult.

A Chërchën man’s rainbow boots.

But the clothing and fabrics found with many of the Ürümchi mummies are vibrant shades of ochre, scarlet, cerulean. Garments are almost fully intact. Somehow, in the arid conditions of the desert, they have remained unfaded and pristine. They almost look like they could have been buried yesterday.

One of these mummies has been named the Chërchën man, dated to be about three thousand years old. As he slept and ate, worked and laughed, Rome had not yet been founded. He has a full beard, striking purple and yellow tattoos on his temples, and is wearing rainbow-colored wool boots. He is also wearing tartan leggings.

Many other fabrics found at these sites are also tartan. Notably, some of them use as many as four thread colors in their design, a feature previously associated with later times and western European regions. In fact, many of the earlier textiles and artifacts are very Celtic in nature. This raises many questions for historians. Who were these people? Were they Celts? Why were they so far east?

It is important to take pause and note that the term for ancient “Celts” paints quite a broad stroke. It is a catch-all term for people who covered thousands of years and thousands of miles, and counted themselves members of innumerable separate tribes. These Celts have no written record, so we must depend on contemporary sources like the Greeks and Romans, who were notorious for seeing little importance in distinguishing with much specificity the differences between one “barbarian” group and another. In fact, the word “Celt” comes from a single tribe that the Greeks called the Keltoi.

Interestingly, there is a famous passage about the Celts from a Greek historian in the first century BC, in which he seems to be describing tartan:

“…The way they dress is astonishing: they wear brightly colored and embroidered shirts…and cloaks fastened at the shoulder with a brooch, heavy in winter, light in summer. These cloaks are striped or checkered in design, with the separate checks close together and in various color.” –Diodorus Siculus

It is probably safe to assume that none of the Celts actually self-identified as Celts. But it can be said that these peoples were at least united by a common heritage, common ancestral language, and similar cultural traditions. And one of those traditions seems to be tartan.

Tartan Clad Mummies

The small alpine town of Hallstatt in present-day Austria is perched on an impossibly tiny bit of land between a glass-surfaced lake and seemingly vertical mountain faces. Despite its precarious position and less-than-ideal location (before 1895 it was not accessible even by road) Hallstatt has been inhabited for millennia. This is because it has a very precious resource to offer: salt. The Hallstatt salt mines have been in operation since antiquity, and with the onset of modern archaeology, they have proved to be a veritable time capsule of artifacts.

Hallstatt, Austria in 1900.

The Hallstatt culture, as it has been coined, was a Celtic culture that flourished between the eighth and sixth centuries BC. At its height, it covered vast expanses in Western Europe, but unfortunately, since it had no written language and existed before the time of the Romans, we can only learn about its people from the clues they have left behind.

Over the last century and a half, over a thousand burial sites have been excavated at Hallstatt. The incredibly saline air and soil inside the salt mines is a perfect preservative, and many things survive there that in other places would have decomposed. In 2004, an incredible discovery was made: several intact pieces of cloth, some of them tartan.

Many of them are remarkably modern looking – one could easily imagine seeing a wool coat out of similar fabrics at many stores today. They’ve been dated to around the tenth century BC, about the same time that the Chërchën man lived.

While we don’t have many surviving artifacts of ancient tartan, the ones we do have are evidence that by at least the early Iron Age, weavers were already quite practiced at creating tartan patterns. It is not outlandish to then assume that the craft had been invented and honed for several thousand years before.

Scottish Uprising

The Hallstatt people eventually died out, but the Celts did not, eventually migrating to the British Isles and bringing their language, culture and tartan with them. By the end of the seventeenth century where our story begins again, the tartan plaid was an irrevocable piece of Highland garb, on its way to becoming permanently attached to the Scottish identity.

As often seems to be the case throughout history, things were uneasy in Scotland at the end of the seventeenth century. In 1688, James VII, the last Catholic English monarch, was deposed and forced to flee into exile. In 1706, the English Parliament passed the Union with Scotland Act, uniting both countries under British rule. Neither event was very popular with the Scots, and various uprisings threatened stability in the northern lands.

One of the most significant rebellious groups was known as the Jacobites. The Jacobites sought to restore James VII—and later his descendant, Charles Stuart—to the English throne. After a failed uprising in 1715, another began fomenting in the early 1740s. Bonnie Prince Charlie, the grandson of James VII, procured French money and support and went to Scotland to gather an army and invade England.

The army, composed mostly of Scottish Highlanders, proved no match for fighting the English forces. After a few small conflicts, the Prince’s forces were defeated in the short but brutal Battle of Culloden in a field outside Inverness. Around 2,000 tartan-clad Highlanders were slain in under an hour.

“An Incident in the Rebellion of 1745” by David Morier, depicting the battle of Culloden. Painted just after battle. Note the many different mismatched tartans.

Culloden marked the end of old Highland culture. In order to stamp out any future uprisings, Parliament passed several punitive laws in 1746. Among them was the Dress Act, part of the Act of Proscription. The Dress Act unilaterally forbade wearing of the traditional Highland tartan outside of serving in the (English) Highland Regiments. Punishment upon first infraction was imprisonment for six months. Punishment upon second infraction was forced transport “beyond the seas” to labor on a plantation for seven years.

It is interesting to see such government emphasis and specificity placed on a fabric. The tartan plaid was so important to the Highland Scots, and so tied to its people’s pride, morale, and willingness to fight, that it was made illegal. A type of fabric was outlawed because of what it meant.

A Romanticized Resurgence

By the end of the 1700s, there was only one company providing tartan for the Highland troops, William Wilson & Sons (WW&S) of Bannockburn. Because of their de facto monopoly, they became very successful and eventually were producing fabric in very large quantities. In order to stay organized, they began to standardize and name their different tartans, some after cities, some after surnames, some with numbers. Some tartans were original designs, and others had been obtained from one source or another around Scotland.

The Act of Proscription was repealed in 1782, making it legal to wear tartan again, though by then most of the Highland men who remembered wearing plaids were gone. Their descendants became interested in preserving their heritage, and several Highland cultural societies sprang up in Edinburgh. They began to record and catalogue tartan patterns, starting with the ones that WW&S had named, whether arbitrarily or not.

Unlike what is widely believed (if you are reading this with your Scottish grandmother, shield her eyes) it is now generally accepted by historians that there were originally no designated clan (family) tartans. In other words, the type of tartan a person was wearing in the time of actual Highland dress was not seen as a black-and-white identification badge. That notion was invented and romanticized by the Victorians decades later and exploited by savvy marketers.

That being said, there would have been regional variations in which patterns were popular, and weavers were most likely restricted to a certain set of patterns by the dyes and resources available to them. Because the members of a clan lived in close proximity with one another, they probably would have bought fabric from the same weavers and therefore had similar tartans. But by and large there are no records showing that the clans of pre-Culloden Scotland identified certain tartans exclusively with certain last names.

So why can you go online and look up any Scottish clan tartan today? What happened?

King George IV happened. He ascended to the throne in 1821 and was immediately unpopular. He was corrupt, manipulative, and quite obese, three things that did not go over well with the public. In the wake of both the American and the French revolutions, the population of Scotland was growing unrestful again, and a group of radicals were threatening to rebel. In an effort to improve his public image and simultaneously appease the Scots, George IV was forced by his advisors to schedule a trip to Scotland, slating himself to become the first reigning monarch to visit the country since 1650. All he had to do was kiss some babies and put on a good show.

Engraving of romanticized Highland chiefs from The Scottish Gael (1831).

And luckily, his Majesty was friends with Sir Walter Scott.

Sir Walter Scott, Scottish novelist and author of works like Ivanhoe, Rob Roy, and the Highland-set Waverly, was put in change of the visit. With quite a flair for the dramatic, Scott organized a days-long celebration filled with tartan pageantry and many ceremonies. Clan chiefs were paraded around in their clan tartans, and the king himself appeared in several different short kilts (with bright pink tights, according to some sources). The visit was quite a hit with the public, and it marked the beginning of the English public’s fascination with Highland Scotland.

These sparks of zeal were fanned into flames by literary works like The Highland Gael by James Logan (1831). But it wasn’t until Queen Victoria took the throne a decade and a half later that the full Scottish obsession took root. She was quite fond of the red “Royal Stuart Tartan,” designed for King George’s visit. She dramatically likened her own spirit to that of the Stuarts, and ordered yards and yards of the fabric be made into garments and decorations and anything else that could possibly have a shred of fabric involved.

Victoria and her husband Albert continued a life-long love affair with Scotland, building their own castle residence there (Balmoral) with specially manufactured tartans in every room. A popular monarch with the longest reign in English history, the people of England emulated their beloved queen in their enthusiasm for all things Scottish.

Queen Victoria and her husband Albert.

In an era of heavy-handed British imperialism and global expansion, the English Victorians sought to elevate other cultures that had been, in their eyes, noble and nationalistic. The Scottish Highlands were romanticized, their fighting spirit celebrated, their tartan embraced. Tartan manufacturers and Scots responded, creating all sorts of named “official” tartans for the English to buy. A cynical person might call it taking advantage of a seller’s market. A less cynical person might call it the readiness of a subjugated country to regain some of its lost identity. Either way, it’s how tartan evolved toward the form we know it today.

Like all things, the meaning of tartan has changed over the centuries, but it can still be just as powerful an identifier. The iconic tan and mulberry Burberry tartan pattern is one example; if you grew up in a town with Catholic schools, then so too is each school’s distinctive plaid skirt.

Or take, for instance, the punk movement in 1970s London and New York City. By then, the bright red Royal Stuart tartan was a symbol of upper crust, genteel England. Punks wanted to incite a reaction from those members of society, so they took that fabric and cut it, shredded it, ruined it. This use of tartan was essentially a middle finger in the face of the establishment, and it’s why we associate that red plaid with punk dress.

Madonna’s tartan

Nowadays, tartans are created for just about everything. Most US states have an “official” tartan, with colors chosen for symbolic reasons. When Madonna and Guy Ritchie were married in the Highlands, the Scottish tourism authorities created a tartan just for them called “Romantic Scotland,” blue to symbolize Madonna’s “True Blue” album, yellow after her “Blonde Ambition” tour, and white after her “Like a Virgin” song. Yes, it’s a real thing.

It is amusing to contemplate that perhaps all of this could have come from one person, five thousand years ago, sitting at a loom with the long monotony of the day stretching before him or her, suddenly wondering what it would look like if one of the threads was a different color.

Throughout history, that color became so much more than the dye, the thread, the stripe. It became a meaning, a message, a way to broadcast allegiance. It is a testament to the universal human need to feel a sense of belonging.

It’s the reason a Scottish grandmother might still stubbornly sip her tea from her “Macintosh tartan” mug, thank you very much.

It’s because she’s a Macintosh.