Racing home from the flea market, 21-year-old Claire McCardell, future fashion designer and leader of the "American Look," rushed into her dormitory room at Parson’s Place des Vosges campus in Paris. Pulling a crumpled wad of satin out of her bag, she grabbed her seam ripper and, very carefully, started disassembling a Madeleine Vionnet gown, determined to unlock the mysteries of couture construction before flawlessly sewing the garment back together.

1926 was a good year to be in Paris. American expatriates like F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway had settled in the city of light, riding the waves of success from publishing The Great Gatsby and The Sun Also Rises. George Balanchine could be found choreographing La Pastorale for the Ballet Russes, while Josephine Baker was performing her danse sauvage in her banana skirt. Meanwhile, in the ateliers, Coco Chanel was revolutionizing women’s fashion with wool jersey and her little black dress while Vionnet explored bias cut garments, and Madame Grès reinterpreted Grecian draping. It was into this heady, creative atmosphere, McCardell had arrived in Paris, eager to explore the city during her time studying abroad.

Years later, while discussing her predilection for deconstructing couture garments, McCardell stated she was, “learning about the important things—the way clothes worked, the way they felt, where they fastened.” She would later use this couture education to create impeccably cut and constructed garments. However, her clothing wasn’t just for the uber-wealthy who could afford haute couture wardrobes—her designs would hang in the closets of everyone from suburban housewives to the fashion doyenne Diana Vreeland.

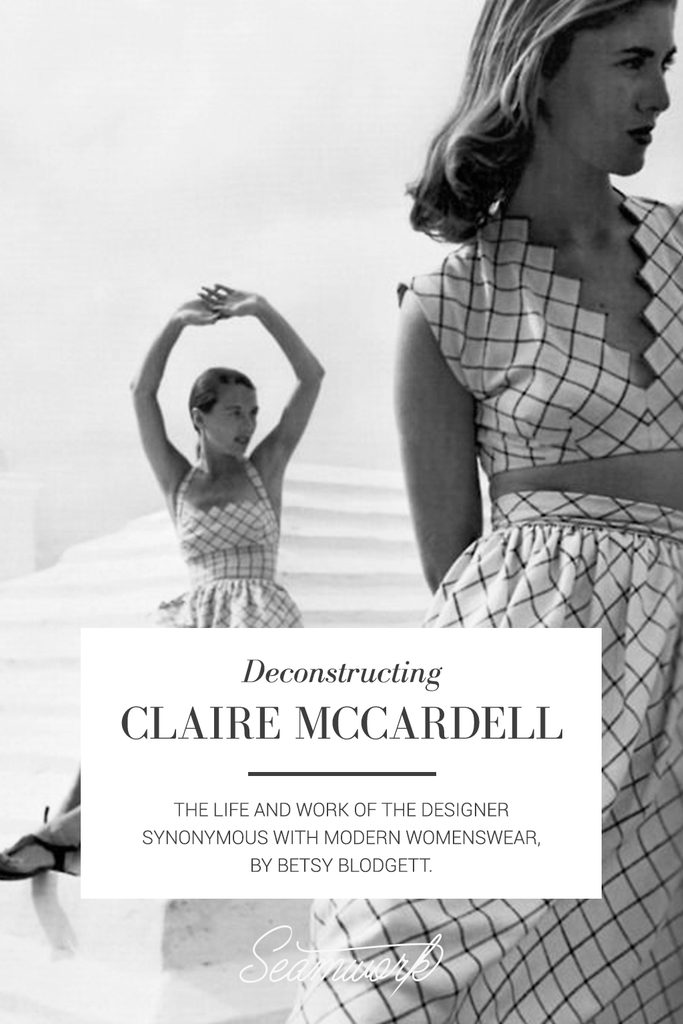

1942 Plaid playsuit photographed by

Louise Dahl-Wolfe for Harpers Bazaar.

Looking at Claire McCardell clothes from a modern viewpoint, they don’t seem particularly revolutionary, an attribute that was often accredited to McCardell during her career. However viewing them in light of her contemporary designers, we see how many “firsts” McCardell introduced that went on to become mainstays in fashion. As Valerie Steele, Museum Director at the Fashion Institute of Technology, says in her introduction to the book Claire McCardell, Redefining Modernism, which accompanied their 1998 exhibit, “We also wanted to place McCardell’s work within its historical context because many of her innovations have become intrinsic to modern fashion. [...] Indeed, part of my problem appreciating McCardell had to do with how thoroughly her ideas have been assimilated in contemporary fashion.”

Early Years

As a child, Claire McCardell had spent much of her early years glued to Annie, her mother’s dressmaker’s side, watching her create the intricate fashions of the early 1900s. As Annie would sketch, drape, cut and fit the garments for the McCardell family, Claire would sit and observe, sometimes getting to collaborate with her own design ideas. “Claire would hang around her and watch as much as she could,” Bob McCardell, Claire’s brother, explains. “She knew what she wanted to do from the time she was a child.”

One of young Claire’s favorite pastimes was poring over her mother’s fashion magazines, cutting out the fashion illustrations to use as paper dolls. However, she was never quite satisfied with the fashions as given and would constantly dissect the garments, interchanging the sleeves, bodices, and skirts to make new fashion—to make it, as she said, "better." Later, as a teenager, she would continue her dissection of clothes, but this time using her and her brother’s garments, giving her a lifelong appreciation of menswear details and construction techniques. When it came time to attend college, she successfully lobbied to leave home for New York to attend the School of Fine and Applied Arts, which would later become known as Parsons School of Design.

At the time there was no training in fashion design, that was purely the territory of the French. It was to France that the world looked for sartorial statutes, Paris acting as Mount Olympus from which the fashion Gods handed down their decrees. Unlike the media throngs of today, fashion shows were hushed, elegant affairs. At Chanel, models would appear like magic, glide down the twisting staircase and disappear just as quickly. The audience, that carefully chosen mix of fashion’s cognoscenti, couture clientele, high-end buyers, and journalists, would note the garments that caught their eye. For them, a private appointment after the show would be time enough to take in the details.

A closer look at the audience would reveal a smattering of intruders. Women who on the surface looked like potential wealthy customers, but were in fact, attending in disguise. These were the pirates, the copy illustrators who acted as spies for dress manufacturers. No Seventh Avenue dress manufacturer designed their own clothing, they all relied on the genius of Paris for their designs. If they couldn’t get a spy into a fashion show, they sent them to high-end stores to sketch designs, or resorted to shadier methods like bribing workers to sneak them backstage to see the collections before they were shown.

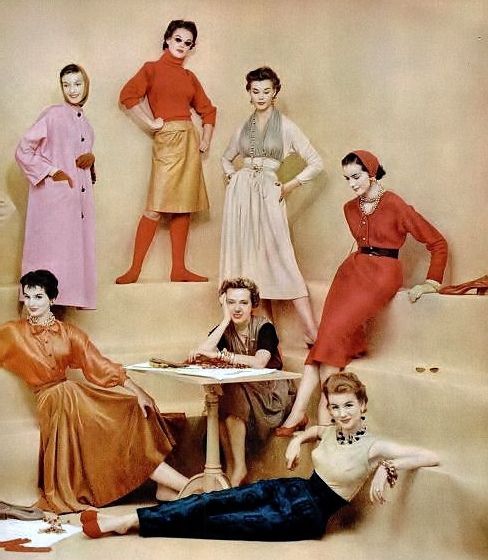

Claire McCardell working in her studio.

McCardell, who never understood why a woman in New York would dress as if she were on the Champs Elysees, chafed at the short-sightedness of the manufacturers. As she bounced from job to job, she yearned to do more than copy from the French. Finally, she found herself a position with independent designer Robert Turk and with him finally received a true education in the fashion industry. As his assistant, she did everything from shopping for buttons to helping design garments. For two years she had hands-on experience working with Turk and became indispensable to the designer. When Townley Frocks, a mid-market manufacturer, made an offer to purchase Turk’s business and position him as their chief designer, Turk agreed, bringing Claire McCardell with him. After Robert Turk drowned in a tragic boating accident in 1932, Townley gave McCardell her first big break, letting her take over Turk’s position. With the reigns finally in her hands, McCardell slowly started filtering her own design ideas into the Townley collections.

Townley Clothes

The key to McCardell’s design ethos was her determination that design should solve problems. In later years, McCardell would attribute her success to a simple philosophy. “I’ve always designed things I needed myself,” McCardell stated. “It just turns out that other people need them too.” And what McCardell needed was an easy wardrobe full of comfortable, but stylish, clothes for her active life. As a single, working woman in the 1930s, McCardell’s life was a world away from the average French haute couture customer. “I am not a European princess, and my dinners are for six and not sixty,” she later stated, explaining her pared-down design aesthetic.

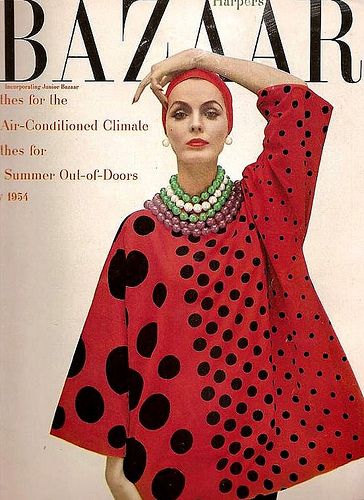

1954 Harpers Bazaar cover featuring a

McCardell T-square top.

Taking advantage of her position at Townley she started quietly introducing the garments that she wanted, while continuing to create the French replicas required by the boss. These early designs had the elements of what would come to be known as her “McCardellisms,” unique design elements that would be her signature: cinch belts, wrap waists, uncommon notions that were normally only used on ski sportswear and even the first “separates” collection. Much to Claire’s dismay these radical design ideas would often be shoved to the back of the rack in the Townley buying showrooms, if not left off altogether. The unwillingness of the executives at Townley, including president Henry Glass, to promote McCardell’s independent design ideas increasingly led to tension in the design room.

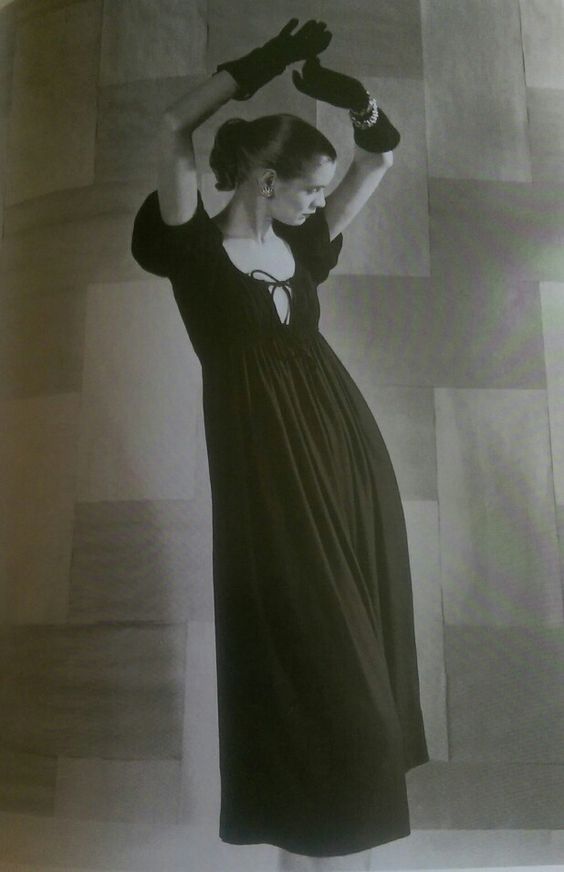

Townley may not have thought that McCardell’s more vanguard were designs worthy of promotion, but it didn’t stop her from wearing them. One dress she designed for her own use was a flowing bias cut gown, which she fitted to herself with a wrap-around spaghetti strap sash. While wearing her dress at work, a chance run-in with a buyer from Townley customer, Best & Co., led to an order of 100 dresses, despite the style not being a part of the Townley collection. The dress, dubbed the Monastic, became a hit, selling out at Best & Co. within 24 hours and spawning a slew of requisite knock-offs from competitors.

Though McCardell was riding high with her Monastic design, the relationship between herself and the executives at Townley did not get any easier. Ironically, Geiss, who had always pushed McCardell to copy Paris designs, found himself fighting to keep the Monastic dress from being copied. To protect their design, Townley employed lawyers to go after its competitors, who were plagiarizing the design. Ultimately, so much money was spent on litigation that Townley was forced to go out of business the following year.

A loose-fitting dress gathered at the waist, similar to the Monastic style.

Suddenly out of a job, McCardell found herself recruited to work with prominent designer Hattie Carnegie. However, Carnegie’s elite clientele expected a certain level of decoration to their garments. McCardell, who believed in function over form, found herself designing garments that were simply too plain for Carnegie clients.

Stepping into an elevator almost two years after Townley had ceased production, McCardell found herself riding with Henry Geiss, her old boss at Townley, and his new backer, Adolph Klein. In the short ride Geiss revealed to McCardell that Klein was going to re-launch Townley, and in the ensuing conversation, effectively buried the hatchet with his once adversarial designer.

As the elevator ride ended, Klein spontaneously asked her to come back as the Townley chief designer. A shocked McCardell disembarked, promising to consider the idea, before Geiss could express his alarm. McCardell certainly wasn’t Geiss’ first choice as designer. Despite her success with the Monastic dress—which had previously toppled Townley—she didn’t have a strong track record on Seventh Avenue. “If I were you, I’d go shoot craps with the money, ” an industry contact later told Klein and Geiss. “It’s not as much of a gamble as Claire McCardell.”

Klein however, was willing to bet on McCardell. “In this business, you have to be exciting or basic,” Klein said. “I figured we were too small to be basic, so we had to be exciting.” McCardell signed on—with a few caveats: One that she had final say in all the designs, the other that her name appear on all the clothing labels, which was unheard of for most designers at the time. All in all, it was an especially productive elevator meeting.

McCardell modeling her “Futuristic" dress

made of triangular pieces.

McCardellisms

“Sports clothes changed our lives because they changed our thinking about clothes,” McCardell wrote in a 1955 Sports Illustrated article. “Perhaps they, more than anything else, made us independent women. In the days of dependent women—fainting women, delicate flowers, laced to breathless beauty—a girl couldn’t cross the street without help. Her mission in life was to look beautiful and seductive while the men took care of the world’s problems. Today women can share the problems (and possibly help with them) because of their new-found freedom.”

McCardell herself was no delicate flower. A tomboy as a child, she never lost her penchant for adventure and her experiences made their way into her designs. An avid traveler, she devised a collection of skirts, tops, pants, and jackets that could be mixed for day and evening, thus simplifying her luggage. She then introduced her wardrobe system in one of her Townley collections—where it fell flat. Buyers in the mid-1930s just couldn’t understand the radical concept of a wardrobe composed of mix-and-match separates. In fact, the idea was decades ahead of its time. Separates finally became popular in the 1950s, but the idea of the capsule wardrobe really took hold in 1985 with Donna Karan’s Seven Easy Pieces, and the concept is still popular today.

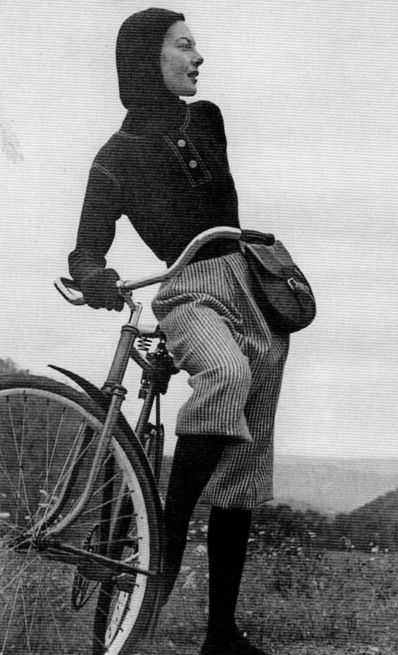

A penchant for skiing often took McCardell to the slopes, where she loved wearing her comfortable pant and jacket ski uniform. One especially cold and windy day she longed for a hat that would cover her ears. She promptly designed a hooded wool jersey top—a forerunner to today’s ubiquitous hoodies. She also developed sporty bicycle-riding ensembles based on her ski-wear, incorporating the ease of movement she loved.

With the advent of World War II, women’s taste in fashion finally started to catch up with McCardell’s vision of simplified, functional clothing. She likes “buttons that button and bows that tie.” She is, said Dallas Retailer Stanley Marcus, “the master of the line, never the slave of the sequin.” Marcus continued, “She is one of the few creative designers this country has ever produced.”

A McCardell riding outfit featuring

a wool jersey hooded top.

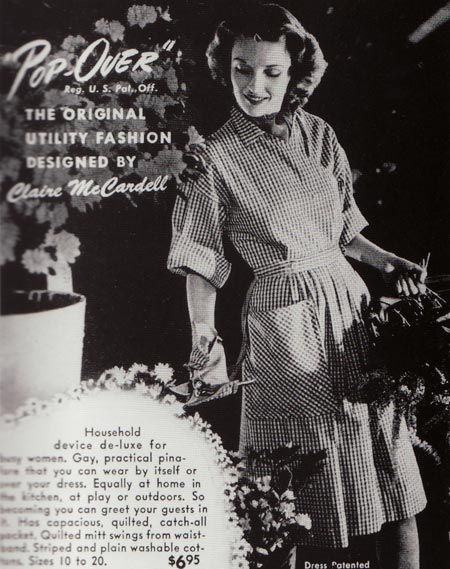

Ad for McCardell’s Popover dress.

Perhaps McCardell’s greatest triumph during the war years was her Popover dress. It was a challenge entrusted to McCardell by Harpers Bazaar editor, Diana Vreeland, to create a garment for women who wanted to throw a stylish dinner party but had lost the staff to cook and serve it. McCardell came up with a denim wrap-front dress. It was simple, chic, and even came with an oven mitt. The $6.95 price tag made the Popover even more appealing, as it sold hundreds of thousands of styles. A version of the Popover wrap dress was included in collections for the rest of her career.

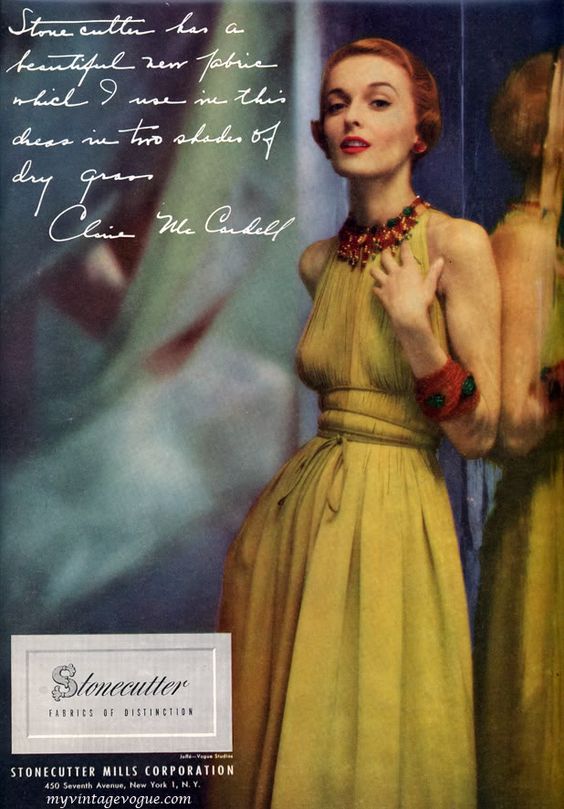

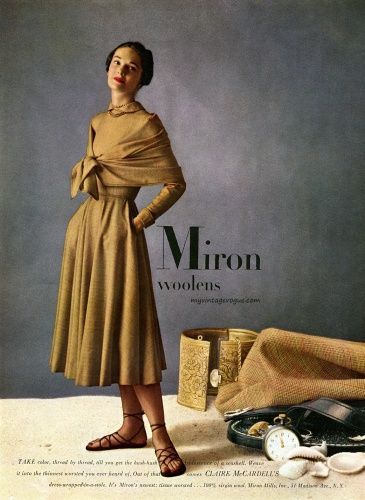

McCardell dress featuring

Miron Woolen fabric.

Where other designers bemoaned the limitations of World War II rationing, McCardell embraced the constraints as an opportunity for creativity. She incorporated unusual and inexpensive fabrics in her designs like denim, mattress ticking, butcher’s apron linen, rayon faille, and even weather balloon cottons. These utilitarian fabrics had never before found their way onto clothing racks. But when paired with McCardell’s designs, which would often incorporate couture construction ideas she had learned during her time in Paris, they created flattering and durable garments.

Metal shortages caused problems for many manufacturers who relied on zipper closures. But, McCardell, who never cared for zippers, preferred to design dresses that didn’t need closures, like her Monastic dress. Her loose-fitting dresses would instead close with a wraparound sash, allowing the wearer to choose the most flattering placement. For her dresses that did need a closure, she used unusual fasteners like hooks, clips, and eyelets.

One of her most ingenious wartime inspirations is still being worn today. When shoe leather supplies were short, McCardell, who always wore flat shoes, had to come up with another option. She approached Capezio, a dance shoe maker, about the idea of making their ballet slippers with a hard rubber sole. Together, they combined her fabric with their sole to create the ballet flat shoe. When she debuted the style in her next collection, the audience broke out into applause.

The American Look

The war had opened the doors for changes in fashion, especially for American designers. During the years when the ateliers were shuttered in Paris, manufacturers had no other choice than to cultivate their own designers. Banking on the groundswell of patriotism, Lord & Taylor began to heavily promote these homegrown designers as the "American Look.” Marjorie Griswold, a buyer for Lord & Taylor who was known for discovering new designers, had seen potential in McCardell’s unconventional designs. With Griswold’s guidance, the public (and the retail world) started to understand the brilliance of McCardell’s forward-thinking styles, and McCardell became the face of American fashion.

In response to the newfound national pride of American design, Coty Inc., a cosmetics and perfume company, developed the Coty fashion awards, specifically to honor and promote American fashion designers. The first award went to designer Norman Norell, with McCardell, Hattie Carnegie, and Valentina among those receiving special honors. McCardell would eventually win her own first prize award the following year.

“[McCardell] should have had that first Coty Award for American fashion back in 1943 instead of me,” Norell said decades later. “Don’t forget, Claire invented all of those marvelous things strictly within the limits of mass production. I worked in the couture tradition—expensive fabrics, hand stitching, exclusivity, all that—but Claire could take five dollars worth of common cotton calico and turn out a dress a smart woman could wear anywhere.”

Legacy

McCardell dress made with

fabric designed by Marc Chagall

for LIFE Magazine.

Though McCardell’s designs were available to the public at off-the-rack, mass produced prices, her young, modern designs made her a permanent feature in high-fashion magazines like Vogue and Harpers Bazaar. Her design prowess was so esteemed that in 1955 she even partnered with some of Europe’s best artists, like Picasso, Chagall, and Miro, using their fabric designs with her garments for a feature in LIFE Magazine. That same year she landed the cover of Time, only the third fashion designer to have done so.

In the winter of 1958, weakened by a cancer that would take her life in just a few short months, McCardell insisted on attending a final showing of her clothes, much of which she had designed while in the hospital with help from her friend Mildred Orrick. Only 52 when she died, McCardell was mourned by the fashion industry and the generations of women who collected her clothes. The Coty Hall of Fame awarded her a posthumous induction later that year.

Townley, who had made her a partner in 1952, closed soon after. As McCardell’s brother Adrian said, “We decided to let the name die with her—it wasn’t that difficult. Claire’s ideas were always her own.”

McCardell surrounded by her designs,

including one of the first leather skirts.

In 1998, an exhibition at the Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology reignited interest in McCardell. Once more, her avant-garde ideas won her rave reviews. “She was a pioneer,” said designer Geoffrey Beene. “She contributed beautiful and pragmatic ideas to get us where fashion is now. [...] She used humble fabrics and couture styling. For her to have done that, at the prices she did, was extraordinary. Her dresses were a luscious bargain.” Looking through the lens of time, fashion historians pinpointed how integral her designs were to the way we dress now. As Valerie Steele remarked, “It is impossible to imagine a Calvin Klein or a Donna Karan or a Marc Jacobs had there not first been Claire McCardell.”