A thin, tattered quilt has lain across my bed for as long as I can remember. The peach backing has pilled and faded to a strange gray-orange. One square bears a purple stain, a reminder of one of the first times I tried to use nail polish. The twelve Sunbonnet Sues are in various states of disarray: torn shoes, missing sleeves, and tattered bonnets. A sewing machine’s zig-zag stitch holds parts together, in contrast to the perfect stitches my grandmother’s hand originally used to make the quilt.

I was looking at this quilt as a pre-teen when I realized that no one else in the family knew how to quilt, and as her only granddaughter maybe I could carry on her legacy. My mother hated our sewing machine, and I could only use a needle and thread well enough to wrap my Troll dolls in crude tube dresses. Yet, somehow, my grandmother could take fabric from the 20-gallon cardboard drums in her basement and make something useful, beautiful, and perfect.

I spilled all my questions into a letter, and so she would understand the urgency in my mind, I added, “Please don’t let this skill die with you.” Then I took a stamp from my mother’s desk and put the letter in the mailbox with the red flag raised.

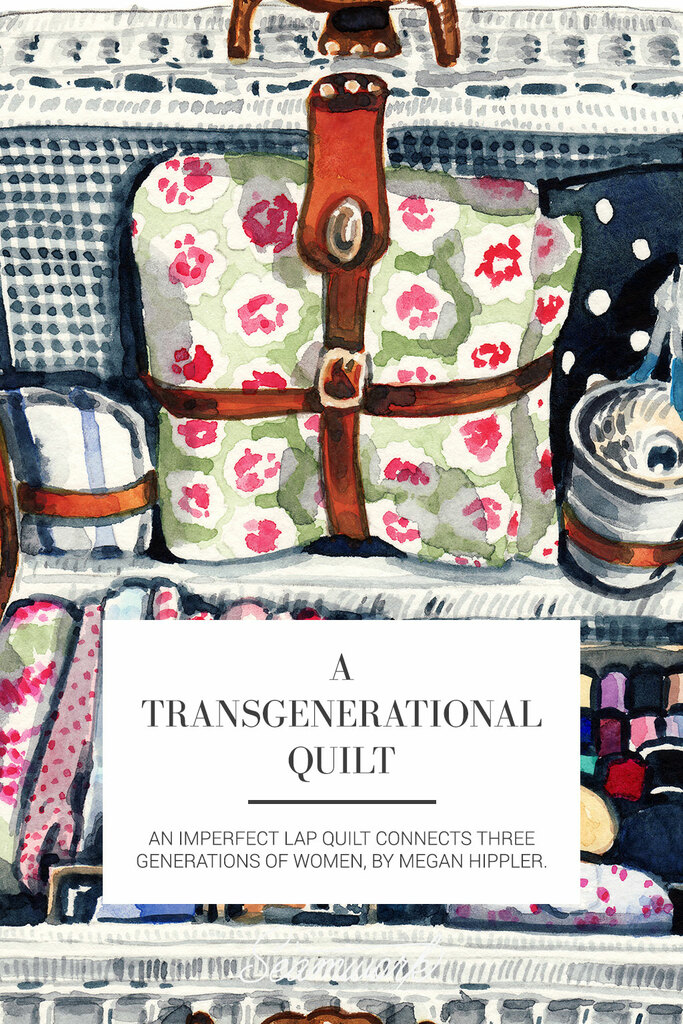

A week later, a slightly battered coffee maker box arrived for me. My parents were confused, but the return address said it was from my grandmother. I tore into the box, surprised that she hadn’t simply written me a letter in return. Instead, I found a small roll of batting, a case of pins and needles, a silver marking pencil, and fabric. Assorted fabric circles laid with a stack of fat quarters, pre-cut squares in two different pinks, and a large piece of white fabric.

Pressed against the side of the box, I found a sheaf of small papers covered in her curling handwriting. She explained how I could combine the small squares into a checkerboard pattern and how to use that to make a proper blanket. She’d drawn diagrams for me, chosen fabrics that she thought I would like, and left me with some words of wisdom: “Megan, you might want to make a doll quilt first.”

Armed with my grandmother’s instructions and her belief that I could do this, I immediately threw myself into my new hobby. I practiced sewing two fabric circles together, flipping them inside out, and finishing the edge to make a floppy coaster. I made more small pillows than I could use, simply to practice sewing straight lines. A quilt, even a small one, I knew, would be my largest project to date, and it would involve measuring, lining up patterns, and sewing as precisely as possible.

My mother offered to help with the top of the quilt, as long as we did it on the sewing machine instead of using my grandmother’s hand-sewing method. I accepted, telling myself I would do it the way grandmother intended for the next quilt. My mother dragged out the old noisy ironing board and set it up in the laundry room with the sewing machine on top. As she tried to reacquaint herself with how to run the thread through the machine without jamming it, I started pinning small squares of fabric into lines. With one strip complete, I sat in front of the machine and followed my mother’s instructions to sew forward-backward-forward at the start of one line and slowly, I was sewing.

We spent a long while side-by-side at that machine, making strips of alternating pinks together as I learned how to be more sensitive on the foot pedal, how to keep the stitches straighter, and how much I hoped to never have to make another bobbin again. As I relaxed into the process, I began to enjoy the way I was making something useful. I never felt more connected to my grandmother than when I was finishing the last line of stitches on the checkerboard quilt top.

We used the little roll of batting to guide the final size so I wouldn’t have to worry about combining two pieces of batting. Carefully measuring, I cut the batting slightly larger than the quilt top and pinned on the plain white backing. My mother called it a lap quilt: something too small to cover my legs completely but too big to be just a doll’s blanket.

My mother left the hand quilting to me, so I spent days sitting on my bedroom floor with a needle in hand desperately trying to mimic the straight lines that the sewing machine had produced. I managed to tuck the backing around the batting to meet the top and sewed it together with my sloppy stitches until I had a small, imperfect quilt.

I never became as enthusiastic about quilting as my grandmother. She used any excuse to make another one to give as a gift, because every room in her house already had at least one quilt. When she passed away, a few years after she sent me her homemade quilting kit, I didn’t mind that her drums of fabric were donated to charity. I had her quilt, my memories of her, and the little lap quilt I made from the fabric my grandmother had chosen, the top my mother had helped me piece together, and the quilting I had done with my own hands, just the way my grandmother’s letter had shown me.