Last month we started our discussion on the degendering of fashion by introducing the terminology used in the contemporary discussion of sex, gender, and presentation. To refresh your memory, sex refers to the biological sex of a person—from sex chromosomes to primary and secondary characteristics to hormonal levels. Gender, on the other hand, is the societal construct that includes roles, relations, and dress. In many Western societies, sex and gender are related, and gender is assigned based on sex to an individual. Presentation, finally, is the way a person expresses their gender, but it can be influenced by other factors such as personal safety and style preferences. In practice, one should never assume somebody’s gender based on what they wear.

This month, I’d like to cover the next step of this conversation: How did we get here? And what can we do now?

Let’s start with how we got here. This invention of gendered dress is fairly recent. It’s not constant across cultures or time, and it is not based on any particular inherent—or “real” if you will—distinction. Therefore, it’s not necessary.

A Very Western History of Seamstresses and Tailors

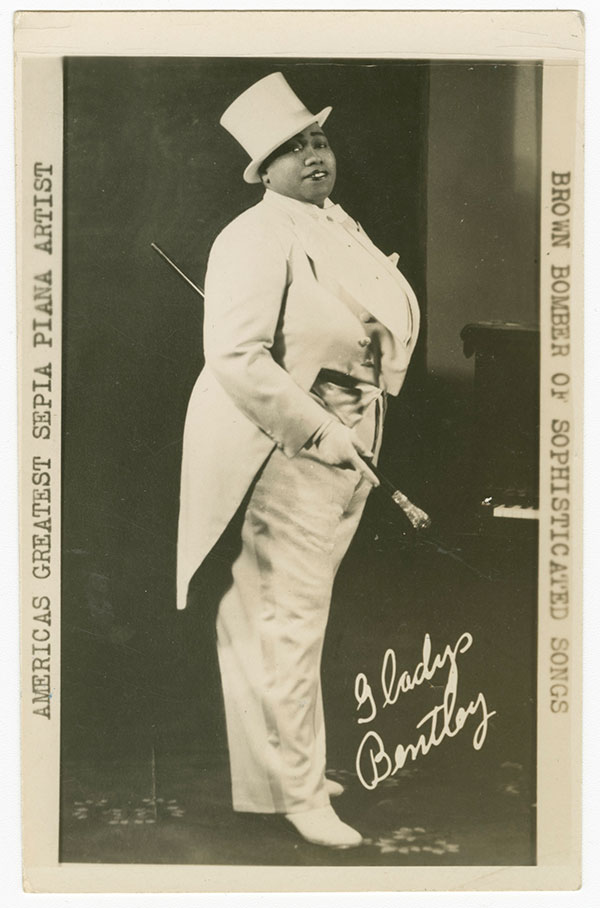

In the West, until the 17th century, womenswear and menswear were fairly similar. They were both based around a tunic-style garment and made by the same professionals—the tailors. Generally speaking, the clothing divide was based on class and not gender. The great divide, which is the precedent of the gendering of clothing we see now in the West, started in France.

By the reign of Louis XIV, a group of seamstresses started organizing themselves in a separate guild, distinct from tailors, and dedicated themselves only to women’s fashion. At this point, fashion (for women) and tailoring (for men) went their separate ways. Fashion, due to its proximity to women, was cast as exaggerated and frivolous—distinct from tailoring.

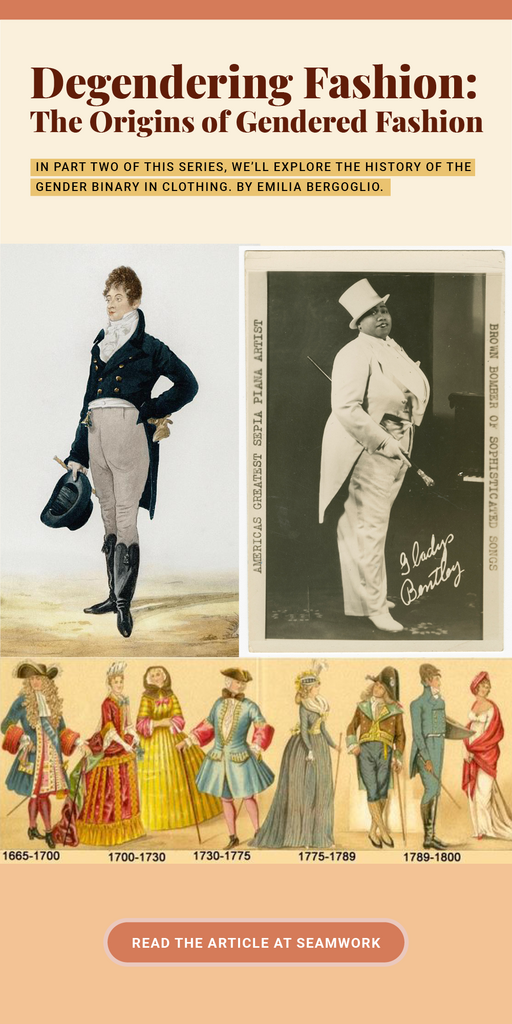

Then, in England’s Regency period—from about 1790 until 1820—a new style became popular, spearheaded by people like Beau Brummel. Brummel is often called the arbiter of fashion for men at that time and was one of the most well-known historical reference points for dandyism. The new style from this time period paved the way for the modern suit.

Differences in dress became more and more gendered until gender itself became a binary so entrenched in the popular imagination that it started having a life of its own. People were rigidly classed into one of two genders, with dress rules so unbreakable that many countries had cross-dressing laws.

Over the centuries, women have borrowed items of menswear, from the shirtwaist to the pantsuit. However, the opposite was not true, which is evident even now in “woke circles,” where “inclusive” fashions are often simply adapted menswear—suggesting that menswear is the standard.

This binary framework for clothing is also evident in a colonial and racial context. Europeans saw the lack of strong gendered dress distinction in many Asian and African societies as evidence of cultural backwardness.

How do we Accommodate all Bodies?

While gendered dress may seem completely benign, it can present a problem for people who live outside of the gender norms of their society. Even for people who generally conform to gender norms, it restricts the choices available to them, as anyone who couldn’t find a piece of clothing in their size or in a color other than neon pink can attest. Since there is no strict need for these distinctions, what can we do to make shopping—and sewing patterns—inclusive and welcoming for all while also not eliminating people’s options?

There is no question that differences in bodies have to be accommodated. The approach I wish to see is gender neutral, not unisex. I’m not questioning the need for bust darts, higher rises, or long socks. Even in pattern drafting school, cutting is taught based on the differences in body shape between the sexes. This also includes making clothing based on the average, which is a problem. Even among people of the same sex, there are many variations in bodies.

The title “women’s tops” doesn’t actually mean anything outside of a specific cultural context—what tops are we talking about? Blouses? Tanks? Shirts? Oversized? Slim-cut?—I’m so confused.

In my mind, the solution is simple. I question giving items a gender that is separate from that of the wearer. So, how about this: Imagine going to a clothing store and seeing items divided by type with a handy description. The title “women’s tops” doesn’t actually mean anything outside of a specific cultural context—what tops are we talking about? Blouses? Tanks? Shirts? Oversized? Slim cut?—I’m so confused.

However, “bust-darted shirts” and “fitted camisoles” actually describe the items, making searching for said items way easier. Also, the lack of gendered markers makes shopping a more inclusive experience for everybody.

Clothes Don’t Have Gender

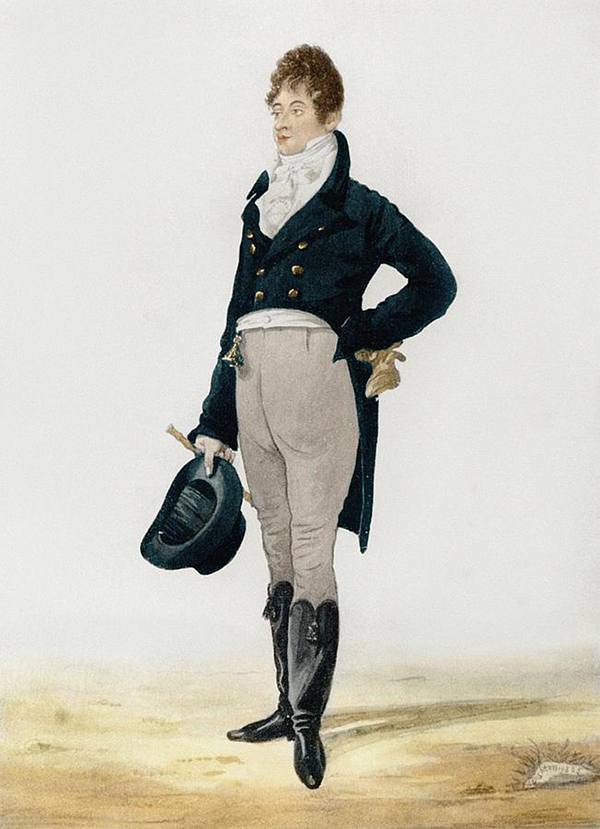

In some ways, we are already getting there—in the last ten years or so, there has been a trend towards increased gender-bending in fashion, and the idea has become more accepted. But in total frankness, what I have seen is mostly the appropriation of what is considered “classic menswear” for the female body. This goes back to the point I stated before, that menswear is the “standard,” and the only thing left to do is adapt it for people who are not men.

The opposite approach—men wearing “women’s” clothing—is really not new. In the West, it has been pioneered by queer communities of color. Only in recent years, however, has it become more accepted. In my opinion, gender-bending is not only not enough but is even potentially backward in that it fails to address the root of the problem. We should completely remove the association of certain clothing with a specific gender and instead accept people wearing whatever clothing they want.

Clothes are just clothes and are only a proxy of expression—they don’t have any gender of their own separate from the wearer. In practice, this would mean simply letting go of the womenswear and menswear labels and describing styles—while also expanding sizing to cater to more people.

Of course, I also live in the real world, and I can see problems where ready-to-wear clothing is concerned. For example, one reason men’s shoes start at a UK size 5 is that, according to manufacturers, there aren’t enough size-4-wearing men in the market for Oxfords. However, if sizing expanded to include smaller feet and a corresponding increase in the number of women wearing Oxfords due to a loosening of gendered dressing norms, the consumer base would also increase. The same could occur in the opposite direction for “women’s” shoes, evidenced in the market shift towards larger sizes in recent years. Overall, there would be no need to generate new products, but only to re-market the existing ones as genderless and reconsider the relative production of different sizes.

In this part of the series, I have discussed the origin of the gender binary in clothing, which in the West traces back to the 17th century. From then, the separation between “serious” menswear and “frivolous” womenswear became more and more entrenched, even informing modern “unisex” fashion. Gendered distinction in clothing is a purely cultural question, which can cause harm to some people and limit the freedom of others.

Can we imagine a world where this distinction does not exist?

Next month, in the final part of this series, I will speak to some fellow trans people to discuss what can be done to empower folks and give sewists the power to adapt styles to fit their bodies.