Cultural appropriation once again became a popular topic in the online sewing community after the March 16 Atlanta shootings that killed eight people—including six Asian women. The shootings took place amid a national surge in reports of violence against Asian Americans.

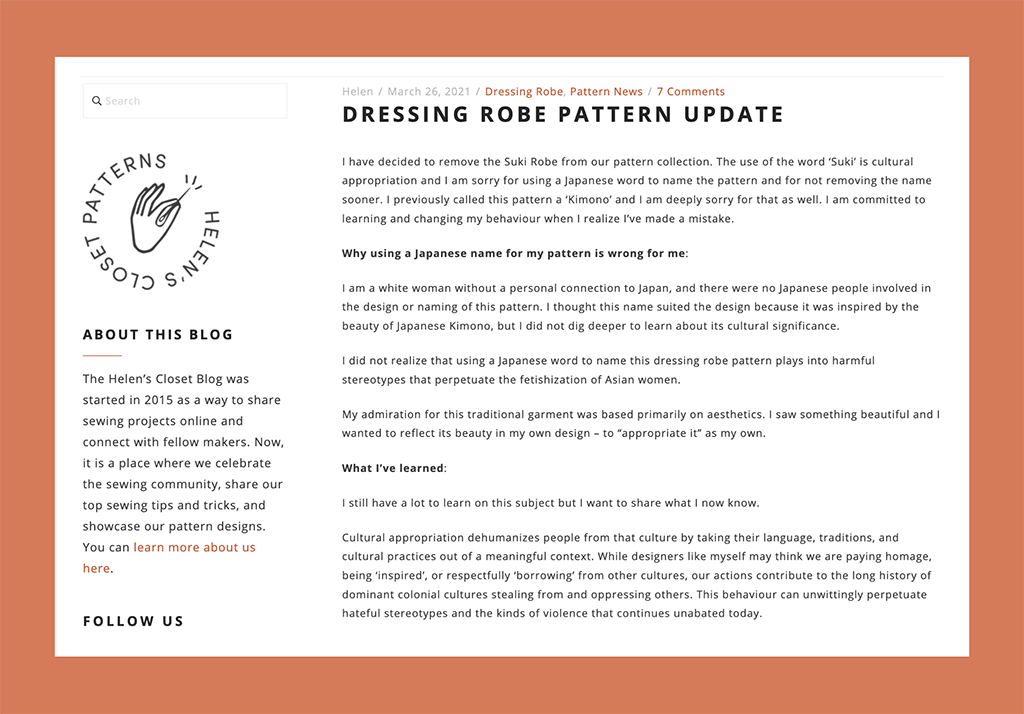

Pattern designers like Papercut Patterns, Paradise Patterns, Wiksten and Helen’s Closet quickly reflected on their business practices and renamed or discontinued patterns that had appropriative names and apologized for their actions. Blackbird Fabrics and Seamwork Magazine also removed patterns that contained appropriative language from their stores.

Those updates and other conversations around appropriation have caused some sewists to ask questions, like why these changes are needed, how much intention matters in whether something is appreciation or appropriation, and whether it’s appropriative to use another culture’s fabric or design elements when sewing garments for themselves.

I set out to find out where the line is drawn between cultural appropriation and appreciation in home sewing. To get an answer, I spoke with several individuals who have spoken out against appropriation, a fashion professor, and some sewing businesses who have changed their practices.

A Deeper Look at Appropriation

Cultural appropriation is defined by the Cambridge Dictionary as “the act of taking or using things from a culture that is not your own, especially without showing that you understand or respect this culture.”

Emi Ito of @little_kotos_closet has fought against the appropriation of Japanese culture for years and provides a more detailed definition. In An Open Letter to White Makers & Designers Who are Inspired by the Kimono and Japanese Culture, she talks about power, profit and people:

“Power first because there is almost always a power dynamic of a more dominant culture taking from another culture that has been historically oppressed and marginalized. Profit because someone is typically profiting in our capitalist society and often it is not the origin cultures and communities. And people because the people of the origin cultures almost always get erased.”

She elaborated on this in an email to me: “When we have white makers who are in a position of power, profiting off of cultures that are oppressed, whose people are literally under attack and continue to be unsafe and in some cases, unprotected, then yes, it is cultural appropriation and contributes to the lack of safety and respect for people who have been historically marginalized.”

Cultural appropriation also involves cherry-picking desirable parts of other people’s cultures while at the same time belittling or joking about other elements of those same cultures, adds Leila Kelleher of @leila_sews.

And names matter, too. On March 18, she posted on her Instagram a series of anti-racist steps the slow fashion and sewing communities could take. One of them was to stop sharing garments that are appropriative in name or garment type name.

“I think that any language that is not your mother tongue is very, very difficult for you to fully understand the deep meaning and nuance,” Kelleher says. Take the word “kimono” as an example. In a 2019 post on the Denshō blog, Ito says that kimono are “garments worn for celebrations, sacred ceremonies, and life’s milestones.” When the term “kimono” is used to describe other garments—such as jackets, tops, coats, sweaters, and robes—it waters down its meaning and significance.

Terms like these also exoticize another culture, Kelleher says. “I think it’s just part of the othering of other cultures in our Western society that leads down this path towards fetishization, for example, because it’s like the dehumanization of people.” She expands on this in her April blog post for By Hand London’s The Creators’ Collaborative.

Some businesses have tried to show their appreciation of another culture by using words from that culture to name their patterns. They’ve learned that impact matters more than good intentions. Sanna Myers of Hawai‘i-based Paradise Patterns (@paradisepatterns) originally named her patterns after Hawaiian flowers to reflect her deep love for her island home and share Hawai‘i’s beauty with others. Myers is white, and the March 16 shootings caused her to look more deeply at her business practices and rename her patterns.

“My intentions are never hurt anyone, but you have to think about the larger picture about the whole colonization and the oppression of Hawaiians and try to see your part in it today,” she says.

Tino Motloung of the sewing blog Sew Star Tino (@sewstartino) cites isishweshwe fabric as another example of why impact matters. This fabric, which is part of her culture, is made in South Africa and has distinct, vibrant patterns. If a brand with no connection to the country were to sell isishweshwe print quilting cotton at a cheaper price than the isishweshwe made in South Africa, it would have a detrimental impact on the country’s textile industry and fabric manufacturers.

Cultural Appropriation or Appreciation in Design and Home Sewing?

Dr. Addie Martindale is an assistant professor of fashion merchandising and apparel design at Georgia Southern University who often talks about cultural appropriation with her students. Fashion designers will often draw inspiration from other places, but what determines whether their actions are appropriation are the acknowledgment of the culture the inspiration came from and the extent to which their design is an exact copy.

Blogger, sewist, and bag pattern maker Cristy Stuhldreher (@loveyousew) says sewists—regardless of their ethnicity—can incorporate Mandarin collars and frog closures, which were part of traditional Chinese garments, into modern designs and turn the final garment into something entirely new.

“It’s a matter of, like, layering the elements where you can give that nod, give that little bit of appreciation but, you know, if you make it your own, there’s something else to it,” she says. “It’s when it becomes a full-on characterization that I think it’s where people feel uncomfortable.” In 2020, Stuhldreher, who is a Chinese-Vietnamese American, shared on Instagram her experience speaking with an indie pattern designer who sold a pattern that too closely copied a traditional Chinese dress by combining narrower flowered frog closures, a Mandarin collar, and a tunic silhouette. That pattern designer quickly apologized multiple times and corrected her missteps.

Appreciation also means paying homage and respect to other cultures and supporting BIPOC sewists, businesses, and artisans. In her list of anti-racist steps, Kelleher suggested that sewists learn cultural sewing practices, like sashiko or shibori, from cultural knowledge keepers (people of that original culture), rather than trying to learn from people who do not have a deep connection to that culture or from books or videos.

Some in the Instagram community have also questioned whether they can own and sew with fabrics from other cultures. One example is Ankara fabric, which is also known as African wax print and comes from West Africa. In her 2020 Guide to Sewing Ankara Fabric, Motloung, who often sews with this fabric, says Ankara fabric has deep cultural meaning and is often used by African women to tell stories. But people of other races can own and sew with this fabric so long as they acknowledge they are using Ankara fabric—not tribal or safari print fabric—and purchase from Black-owned businesses to show support and appreciation for it.

“I love it when people tell me stories about the fabric, like, you know, ‘when I was in Africa, I bought an Ankara piece and when I bought it the vendor was telling me this print is inspired by this and it was named after this,’ and that you could actually use that to educate even your following…” she tells me. “That for me shows true appreciation of the fabric.”

Accountability in Sewing

Discussions around cultural appropriation are not new in the online sewing community. Caroline Somos, the founder of Blackbird Fabrics, says Ito’s work speaking out against appropriation the last several years “has been a powerful force in asking the sewing community for accountability when it comes to appropriative language.”

“You’re seeing crafters, makers, sewers, more empowered to call out appropriation,” says Martindale, who has written scholarly articles about the home sewing community. “But I think that really is, I think, society as a whole, people are feeling more empowered and more obligation to speak out when they see things.”

Ito says she thinks that everyone has a responsibility to learn and understand more about incorporating anti-racist practices and values into their lives—even in their own homes.

“What we do in any context matters,” she says. “Yes, we could buy patterns from racially privileged white makers who are profiting off of oppressed cultures and peoples and then quietly sew them and quietly gift them, but I believe living our values as much as possible is always the right way, whether or not someone is watching.”

She says she would often be ignored or rejected when she first started speaking out about cultural appropriation. Or sometimes, only partial changes would occur, such as only changing the word “kimono” to something else but still keeping a female Japanese name in the garment name. She says she’s now seeing more thoughtful renaming and redesigning thanks to the greater number of people demanding change.

“There’s still a long way to go, but the more people who live their anti-racist values, the more we will see people being mindful of crossing the line into cultural appropriation,” she says.

After the March 16 shootings, Helen Wilkinson, the owner of Helen’s Closet, quickly removed the Suki Robe pattern from her collection, apologized for her mistake, explained what she learned from this experience, and donated to Elimin8hate and CCNC-SJ. Kelleher says, as an Asian woman, she appreciated the business’ courageous decision and response.

By Hand London also replaced the term “kimono sleeves” with “grown-on sleeves” throughout its patterns. The term “kimono sleeve” has long been used in the fashion industry to describe wide sleeves, Kelleher says, adding that she doesn’t blame pattern or clothing designers for using an appropriative name like that. “But I think what’s important is now the conversation is open and for people to listen and hear and then make the appropriate changes is all we can ask for, and that’s what’s really amazing,” she says.

Somos says the March 16 shootings and Kelleher’s call to action caused her and her employees to discuss what they could be doing differently. They also heard from Asian community members who felt unwelcome in the online sewing space. Some of Blackbird’s changes included reflecting on the language it uses to describe and sell its products and donating to a local organization called SWAN Vancouver that provides culturally-specialized support and advocacy for im/migrant women engaged in indoor sex work.

“We also talked about the fact that so many of our fabrics are made in Asian countries, and we cannot and should not profit off the work of these countries, cultures, and people without acknowledging and working to combat anti-Asian racism,” she says. “We decided to make a long-term change in the way we name our fabrics. In the past, we included the country of origin in the name of certain textiles, for example Japanese, Indian, or European fabrics. We realized that through the naming of our fabrics, we were unfairly placing value on fabrics from certain countries and not others.”

The online fabric store also removed patterns that included appropriative or fetishizing language and reached out to those pattern designers. The pattern designers, she says, have been receptive to Blackbird’s feedback and have been either changing names or discontinuing patterns altogether.

Stuhldreher adds that it’s important to remember that making amends is not for oneself but rather for the party that has been victimized or oppressed. She’s not aware of whether all the brands that have apologized have taken additional steps to donate profits from those patterns to the AAPI community. The AAPI community, she says, has to feel like amends were made, not the other way around.

“These are just not pieces of clothing to us,” she says. “There is a lot of shared burden (wrapped up in wars, trauma, and colonization) with these garments. … Unless you are able to carry these same burdens, you shouldn’t ‘appreciate’ by wearing our history.”

Ongoing Learning

Many of the individuals I spoke with for this story say that they and others are learning from the conversations and actions occurring in the online sewing community.

Myers says Instagram has exposed her to different perspectives, and the discussions she’s seen have taught her to be more mindful and really think about her decisions.

Stuhldreher says she’s been happy to engage in conversations with other people and appreciates their questions and willingness to learn. Some, she says, are apologetic for coming to her with a question, but she applauds them for having the bravery to ask it because that’s how everyone will learn.

Martindale agrees, adding that she hopes people continue learning and are compassionate in educating others: “I think the sewing community has a really good opportunity to keep the conversation going and to educate and to share knowledge and to understand that it’s not someone of that culture’s responsibility to educate you.”