When you buy a t-shirt from a shop you know where it was made. It says it right there on the label. Why, then, if you buy fabric, which is in theory one step closer to the source, do you not get such information?

Aware that new fabric uses resources, I began to feel anxious about this missing information. I wanted to make informed decisions rather than take a lucky dip. So I contacted fabric suppliers and retailers to learn where my fabric came from. I expected it to be difficult, I expected to get vague answers, but what I didn’t expect was silence. Emails with no reply, promises to call me back not materializing.

When it became clear that I wasn’t going to get any answers, even from quality providers, I set about finding out if there was a better way. That is when I stumbled on the Fibershed project by Rebecca Burgess, and I realized that using local fabric would help me understand the supply chain. I hoped that then I would be better equipped to ask the right questions of fabric made further afield.

Photo by Kerry Bardot.

With scant research and a large dose of naivety, I decided to set myself the challenge of making an outfit entirely sourced within 500 kilometers, and I gave myself one year to do it. I didn’t think it could be that hard. I sent an open invitation for people to join me, and thankfully, not everyone thought I was crazy. A small group of #sewcialists and I set to work sourcing local fabric around the globe.

I didn’t think it could be that hard, but it turned out I had a lot to learn.

Sourcing Local Textiles

In southwest Australia, my Fibershed, I had my hopes pinned on two indie textile companies, selling hemp and silk. Two site visits later, I realized with a sense of dread that no fabric, in fact, was made here at all. The hemp was all farmed and milled in China, and the silk cocoons were sent to Bangladesh and made up just 5% of the silk cloth produced. While both of these companies provided great information on their supply chains, I was committed to the task of finding something local, making something uniquely west Australian.

It became apparent that this was going to be a challenge. I switched to Plan B. I worked backwards starting directly from the raw suppliers, to see how far along the supply chain I could get before things moved overseas. For instance, the silk cocoons were sent directly to Bangladesh, so I would either have to work with the cocoons directly or find someone else who knew how to. I also found a micro mill that processed local alpaca, but there were no local spinning mills for wool, so now I needed to find hand spinners. Fellow participant Sue also found barramundi leather available in small, expensive lots.

Each sewist’s particular Fibershed dictated the fibers available to them. In the United States, sewists were able to work with wool, alpaca, and cotton. Mari, Tasha, Jess, and Helen (left to right).

Finding all these sources turned out to require a knack of sorts. And it was a similar experience across the globe. There are small quantities of information on the web, but the real information came from local textile aficionados. The ladies and gentlemen of the local hand weavers, dyers, and spinners groups, the university and college textile groups, the local textile associations, and the local fiber artisans; all of these people have a wealth of information that is best shared over a cup of tea. I learned that there use to be a flax mill in our Fibershed! I learned that it had not been that long since the large woollen mills had closed down and moved offshore. I learned about little shops that only sell local yarn, spun by local spinners. I am finding that talking to more people leads to discovering more, and the learning process keeps on going.

The stories were remarkably similar from participants in the US and Europe. Everyone discovered that the information they needed came from the ground up, from talking directly to the farmers and mills, or to someone who had done this step for you. As a result, the project has created a wealth of information on local supplies, something that I hope to find a neat way to capture in future years.

What Do You Do When There Is No Local Fabric?

Photo by Kerry Bardot.

The next stage was to identify exactly how I would turn the fiber we had found into textiles and clothing, and how to do this in a year. I knew I wanted to create flexible pieces that would work for my wardrobe, and I had also decided at the very beginning that I would take more notice of the natural environment around me so that every design decision would be informed by my locality. I took photographs and learned plant names. I grew up here but I suddenly had fresh eyes. My Instagram account really changed to reflect this. Ultimately, I knew I wanted to make several separates: a vest, a skirt, and a top.

To make these three garments, I had silk cocoons, alpaca yarn, handspun wool yarn, and wool roving to work with. Also, when I started this project, I had some experience with a sewing machine, rudimentary hand sewing skills, and very rudimentary knitting skills.

First, it became obvious to me that I had to learn to knit. And quickly! I got some moral support and began learning in February, where I worked my way through some simple patterns. In April, thinking I had plenty of time, I decided that cables couldn’t be that hard and dove right in with my handspun wool. Fast forward to August, two thirds of the way through the challenge, and my cables were slowly melting into a lumpy mess. Considering I had yet to complete a single garment, I knew that I needed to reassess my entire plan, and fast.

Luckily for me, there were four of us in Perth doing the challenge, and by this point we had become a little team. The other three had all been honing their felting skills, and I could see that felting might be a quick, satisfying win. Perhaps I wouldn’t be naked at the end of the year. Sue helped me felt my wool roving into a lovely piece of fabric, and I worked out how to create holes in the fabric that were traced from bunches of gumnuts. It felt amazing to be holding a piece of Western Australian fabric in my hands at long last. I’d finished my first garment, the vest!

The first completed garment, a vest made from wool felt,

awaits the completion of its companion garments.

Frustrated with knitting, I turned my attention instead to learning to weave. Yes, with just four months of the challenge left, I decided to learn another new skill! Because clearly I am crazy. By now, the project had turned from something I was casually dabbling in every now and then to one that had all of my focus and attention. I had the most generous instructor, Sue Greig from the Guild, who helped me warp up my wool and set me on my way with a four-shaft loom. After some dedicated sessions in October, with just two months to go, I cut two whole meters of hand-dyed, handspun, hand-loomed herringbone twill from my loom and I beamed! Another piece of fabric!

Right from the beginning of the challenge, I had fallen in love with the black swan, endemic to my Fibershed. When I bought the black alpaca I specifically thought that it represented the black swan, and I remained stubborn about having a knitted garment as part of my outfit. Therefore, in November, with the clock ticking down, I reluctantly returned to knitting, this time with a much simpler pattern, and completed the trifecta. I had successfully turned wool and alpaca into fabric by knitting, felting, and weaving.

How Do You Find Local Color?

The range of local colors available to sewists is highly location-specific. Outfits created by Charlotte (UK; left), Nicola (UK; center), and Ute (Germany; right).

I love color. Bright, bright color. However, before I started this challenge, I did not realize the environmental impact of the synthetic dye process. Synthetic dyes, more often than not, contain heavy metals, known and suspected carcinogens, and cause major problems for local waterways. I was keen to find a color extract from nature that was bright and would pop, and which would not harm the environment or be a health risk.

Again, talking to local experts was critical. I met many wonderful people working in this area and tested over 20 local plant parts to see what color I could get on my handspun wool. As part of the process I found myself learning to identify native plants (which is particularly challenging when it comes to eucalypts!). I also learned that handspun wool does not take to dye very well, due to its high lanolin content, and that I could improve the colors I got by giving it a gentle wash in locally-made olive oil soap.

I also found I was restricted by the amount of plant material available for each type of plant and when it flowered. The two colors I was most happy with were a brilliant yellow from a local weed, sour sob, and a lovely light blue extracted from Indigofera Australis with the help of local lime and honey. The indigofera flowered too late in the year for me to use, so I decided to go with the yellow. I used the white and yellow to create the twill pattern in my handwoven fabric. The white and yellow represented our soil, since we basically live on top of sand dunes, and the herringbone weave represented the waves in the sand as well as the birds in flight.

As to that lovely blue—never fear, it will appear in my wardrobe next year!

Many of the sewists working in the Australian Fibershed opted for a natural palette. Carolyn Smith (left); Sue (center); Megan (right).

How Do You Sew with No Notions?

I had learned through this process not to take anything for granted. Turning our fabric into clothing should have been the easy part, right? Wrong.

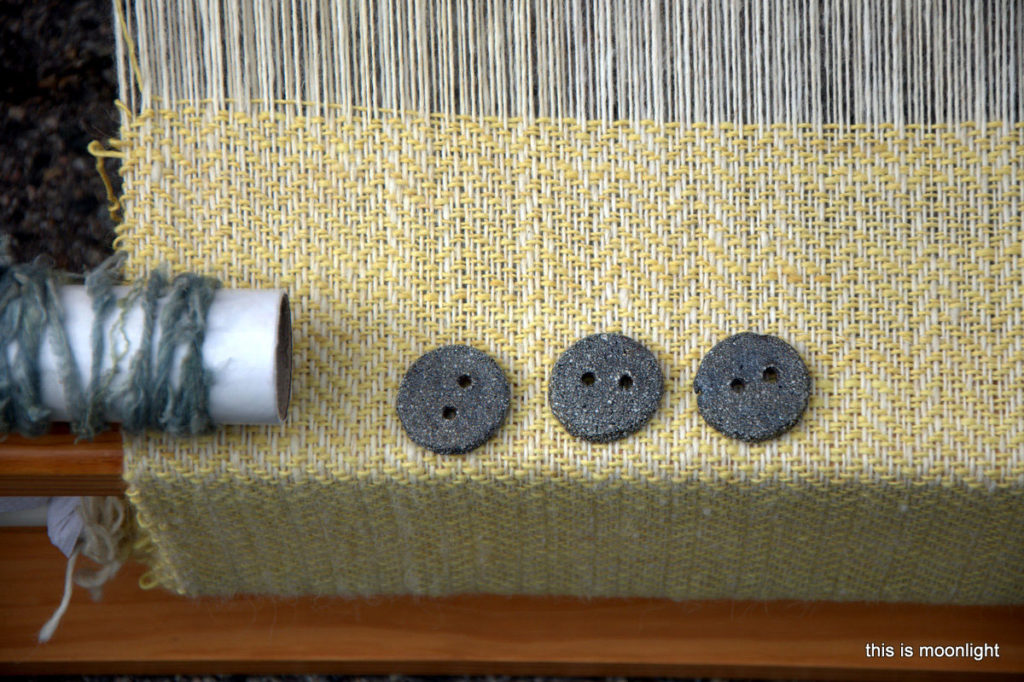

In June, halfway through my challenge, I realized that no thread or notions are made in our Fibershed! So we had to design to this constraint. It took me until August, when I had my major rethink, to hit upon a solution. All the stitching was done with handspun wool or hand-reeled silk, rendering my sewing machine useless. I used felt to face and finish the seams of my skirt. This was not ideal due to its bulkiness, but it does give a lovely pop to the skirt hem. I also designed the tops to have no closures. Finally, I realized I could make local clay buttons to hold my skirt together. Even then, it took me another month to source the clay, and another month to finish making them! In late November I took a sewing weekend away, where I took my cut-out skirt, silk, and wool thread, as well as my knitting. No machine; just me and my hands. I sat and worked for two days straight, and by the end I had myself an outfit!

Nicki’s final outfit was made of local wool, alpaca, silk, clay,

and dye from the local weed sour sob. Photo by Kerry Bardot.

Other ingenious approaches used by participants were Sue’s historically-inspired corset, complete with i-cord ribbons, and Carolyn’s use of a whittled a stick to make a closure for her cardigan.

Reflections

As it turns out, this project was a lot more than just sourcing local fabric, it required a lot of creative thinking and adaptation, an invaluable skill on a planet with finite resources.

As consumers of textiles, I believe that if we want answers, we need to start asking questions of retailers. This year I am continuing to focus on creating local garments, and have opened up the challenge by allowing myself to also work with recycled components and textiles with known supply chains. I would love to see us work together to create gorgeous, responsibly-sourced outfits, and push the industry towards transparency!

Note: Except where specified, all photos are courtesy of the sewists who participated in this project. Sewists who provided permission and photos by March 1, 2016 were included in the article. For additional photos, resources, links to participant’s websites, and information, please visit the 1year1outfit page.