Wool is my all-time favorite fiber. It’s terrific to wear: breathable, durable, and elastic with substantial body yet elegant drape. It’s also wonderful to work with: malleable, forgiving, and takes dye amazingly well. I love sewing with wool—everything from gauzy crepe and jersey knit to thick felted fabrics. I also choose wool yarn for knitting, and I’m learning to spin my own yarn from fleece. I’ve even designed and sold a line of handbags made from hand-felted wool. I’m still not tired of wool, or finished exploring its possibilities. I’m going to guide you on a quick tour of the fascinating history and science of wool. Then I’ll show you how to use its properties to your advantage when sewing and caring for your finished garments.

An Ancient Relationship

Sheep and humans have shaped this landscape near Knocknarea in Ireland together. Photo by Jon Sullivan.

Humans and sheep go back a long time. Historians agree that our ancestors first domesticated the ancestors of the sheep we know today, around 9,000 BCE, roughly the same time that humans started cultivating crops. Historians think these early domesticated sheep were used for meat and hides. The first clear evidence for textiles made from wool yarn began 3,500 years ago.1 The ability to spin yarn and weave fabric from wool led to a revolution in how people dressed.2 Wool takes on color from dye much more readily than the plant fibers that were already in use, especially when using natural dyes and the fixatives for them that were available in ancient times. The development of wool yarn (along with the discovery of silk, which also has a great affinity for dye) was the beginning of the vast array of colorful clothing choices we enjoy today, whether we’re wearing wool or not.

This colorful wool fabric was dyed with natural dyes and hand-woven by my grandmother, Dorothy L Miller.

Humans have been selectively breeding sheep for thousands of years to enhance desirable characteristics in their fleece and meat. Still, going back to the very beginning, the primary purpose of a sheep’s coat is to keep the sheep warm and comfortable, and a lot of what we love about wool is that those traits keep us warm and comfortable too.

Different Sheep, Different Wools

When I started felting by hand, I was amazed at how wool behaved differently depending on the breed. Clara Parkes makes an excellent analogy in The Knitter’s Book of Wool: putting all the fiber from all the hundreds of different sheep breeds that exist today together into one product and calling it “wool” is like pouring the product of all the grapes in the world into one big vat and selling it as just “wine.”3 And it’s true. Some sheep (like Merino) grow wool soft enough to cuddle a baby in, while others grow sturdy wool you may not want on your face, but you’d love to have in a rug because it will last a lifetime. And there are sheep for every fiber in between!

The prickliness many people associate with wool is a product of which sheep grew the fiber, as well as how it was processed and made into yarn and then into fabric. Some people may react to chemicals used in processing, in which case cleaning the fabric can solve the problem. A true wool allergy is rare and results in a rash, not just itchiness. The itchy feeling comes from thicker wool fibers. These fibers don’t bend as easily, so the little ends of fibers sticking out of the fabric poke your skin. Different people can have very different perceptions of which wools feel prickly, according to personal preference and sensitivity. (And even “coarse” wools are much thinner than a human hair!) If you want to make a camisole to wear next to your skin, you’ll probably want the finest, softest wool you can get. But if you’re making a coat or a handbag that you’d like to last for decades, you’ll be happier with a harder-wearing fabric, even if it seems a little scratchier to the touch. Keep in mind that your skin will be separated from that fabric by at least a lining, if not multiple other layers of clothing.

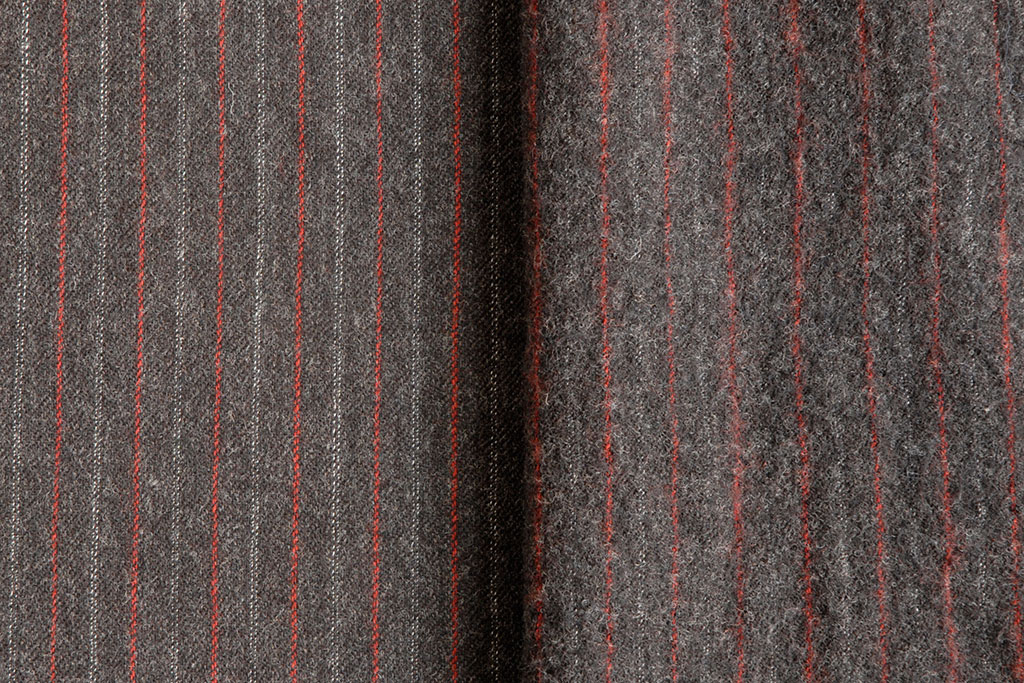

When buying finished fabric, the label rarely says which breed of sheep it came from, so let your fingers be your guide to which wool is best suited for what purpose. Feel wool fabrics for texture, and hold them up in the light to determine their drape and sheen. Smoother, shinier, harder-feeling wools usually have good durability, while fuzzier, more matte fabrics feel softer. Some fabrics have elements of both. A brushed coating fabric may feel soft, but may also be thick and sturdy, and should wear well. The best way to find out which wools work for you is to have fun and experiment!

This flock of Shetland sheep displays some of the many natural color variations in their wool. Photo by Andrew Michaels.

Inside a Fiber

All wools have a similar structure and composition, which gives them the properties that fiber artists love. Wool fibers have a structure similar to human hair: a thin layer of overlapping scales, called “the cuticle,” surrounds the majority of the fiber, called “the cortex.” The cortex is made of two types of cells, which wrap around each other, giving wool fibers their characteristic crimp (like tight curls or waves). It’s the crimp in wool that gives it elasticity and resilience, meaning the fibers can be stretched and folded thousands of times without breaking. The cells in the cortex also make it possible for wool to absorb moisture without feeling wet, and to take in dye.

Looking deeper into the composition of wool, it’s something called an amorphous polymer, meaning a long chain of molecules that aren’t organized in any particular way. When heated, these polymers can reorganize themselves, and assume new shapes, without degrading the wool. Any forces acting on them while they are in transition will affect how they reorganize.4 I always say that wool loves steam—it will assume practically any shape you want while warm and moist, and this is why. Tailors have been precisely shaping wool with steam for centuries, long before we knew its molecular structure.

Fleece into Fabric

Sheep grow these amazing fibers for up to a year, depending on the breed, until there’s enough to shear. Shearing a sheep well and preserving the best qualities of its fleece takes much skill and practice. After shearing, the fleece must be washed, called “scouring.” Then it’s combed and/or carded so that the fibers are separated and aligned or unaligned, depending on the specific yarn they’re intended for. On a commercial scale, many fleeces—hundreds of pounds of wool at time—go through these processes together. The clean and combed wool is then spun into yarn, and the yarn is woven or knitted to make fabric. (See also “Farm to Fabric” in Seamwork Magazine, issue 04 for photos of wool being processed.) The fibers can be dyed at any point, from “in the wool” just after scouring, up to printing on the finished fabric. The specific processing is quite different if the end product is designed to be a squishy yarn for hand knitting, a fine woolen suiting fabric, or thick fabric for a winter coat!

From left to right: washed locks, combed fibers, and yarn in progress. This is a Coopworth lamb fleece from Deer Run Sheep Farm. Processing wool by hand is still an option for me, and other crafters with a sense of adventure. Although I’m no expert at this part, I am learning quite a lot by doing it myself!

Felted, Fulled, or Boiled

Some fabrics take advantage of wool’s ability to felt in order to make a thick and cozy, yet lightweight structure. Felting can be either a huge advantage or disadvantage depending what you want the fabric to do. Some wools felt much more easily than others. If you’ve ever accidentally put a wool sweater through the washing machine and had it come out three sizes too small and thick enough to stand on its own, you’ve made felt. (I’ll cover how not to felt wool fabrics a little later on.) Wool felts because of those little scales around the outside of the fibers. Believe it or not, it’s the scales meshing together that makes wool felt, and once it happens, it can’t be undone (although it can usually be stretched out a little).

Moisture allows the scales to open up, and agitation meshes them together. Warmth, and sudden changes in temperature, can make the felting process go faster. Tightly felted fabric traps lots of air, and resists moisture, but is still breathable because the fibers themselves are. Because the fibers are meshed together, felted fabrics won’t unravel when you cut them, so you can use the raw edges as design elements in sewing.

Humans have been making felt longer than we’ve been spinning wool, and using it for things like rugs and even yurts. Today, felting is what gives some fabrics their warmth, loft, and fuzzy surface. You may see such fabrics labeled “fulled” or “boiled” wool. Fulling is a term for both the second stage of the felting process and for felting a fabric that has already been knit or woven (as opposed to starting with carded wool). Boiled wool is another term for fabrics that have been at least partially felted.

From left to right: handmade felt, a felted knitted sweater, and a commercial fabric lightly felted as part of its finishing.

Sewing Tips for Wool

In fabric, whether finely spun and delicate or thickly felted, the wool retains the properties it formed when growing on the back of a sheep. Wool fabrics have a body and substance to them that’s hard to describe, but wonderful to feel. They also have a slight grip (again from the scales) that makes them stay where you put them. Lightweight wools have amazing drape, and can be quite lustrous without being too slippery under the sewing machine.

A finely-woven designer fabric (later hand dyed) on the left, and a lightweight, loosely woven wool with extra drape on the right.

All wools are easy to gather, ease, and shape, especially with steam. To reshape a section of fabric, pin or baste it in position, then fill the area with steam from your iron. To avoid flattening a fine or textured fabric, hold the steaming iron above the fabric without actually touching it, then smooth it with your fingers after you take the iron away (or use a press cloth). For thick wool fabrics, using pressure from the iron or a clapper will help flatten seams and reduce bulk. For the most precise results, leave the pressed section alone until it’s cool and dry before going on to the next step.

An example pocket, with the fold line marked in white stitching and gathering thread in red stitching. It’s gathered and pinned in place, then steamed to set the wool in its new shape.

Wool’s natural bounce and elasticity also makes it a forgiving fiber to work with. Uneven stitching is less obvious on a wool fabric than it would be on a crisp cotton one. These elastic properties mean it makes great knit fabrics, from sweater knits to fine jersey. (See Seamwork Magazine, issue 01 for more about sewing with sweater knits.) Wool knits have the same easy handling properties as their woven counterparts. As with all knits, it pays to experiment with stitch length, width, and type to match the stretch of your specific fabric.

Zigzag stitching and covered buttons in lightweight Merino jersey.

Care to Last

My favorite way to care for wool clothes is to gently hand wash them. It may sound onerous, but actually it’s ridiculously simple and takes hardly any extra time. All you need to do is get the wool clean, without undue agitation or temperature shocks that might start the felting process.

A hand-knit wool sweater and delicates sewn from a wool/silk blend, soaking clean.

Fill a clean bucket (I keep one just for hand-washing) with warm water and a little mild detergent. Look for a detergent with the Woolmark on the label or one that says it’s pH neutral. Wool (like your skin and hair) is slightly acidic, so alkaline soaps can damage the fibers over time.

Gently push the garment under the water, and then leave it alone for a while. Soaking will remove most of the dirt and oil. If you notice a spot, rub a little detergent into it and then leave it to soak. Leave the bucket for at least half an hour. After that, whatever works with your schedule is fine, even overnight if you get distracted! If you pass by the bucket partway through the soaking, you can rearrange your wooly garment to make sure all of it gets time under the water.

When you’re finished soaking, hold the garment back with one hand, and pour off the water. Refill the bucket with water that’s the same temperature as what you just poured off, holding the garment to the side so the water doesn’t pour directly onto it. Gently squeeze your garment in the rinse water to remove any leftover soap and/or dirt. Repeat the rinse once more, or until the water is clear.

The fastest way to remove the water once your garment is clean is to use the spin cycle of your washing machine. Spinning will not cause the wool to felt (it needs agitation back and forth for that). Make sure your washer is set to spin only, not to add water or agitate. If that’s not an option, you can also roll the garment up in a towel and squeeze the whole bundle, or even stand on it, to remove as much water as possible. Then hang your woolens to dry, or spread out to dry flat, especially if they’re heavy.

To make a tailored garment (or anything made of wool) look amazing, give it a good press once it’s dry.

Wool responds very well to warm water, but check that any other components of your garment are also washable before you clean it. When I sew with wool, I make sure everything I add (interfacing, linings etc.) is also washable, and tacked in place with stitching if necessary, so that it will come out of the water looking great. If you’re not sure that everything in your garment is washable, the safest bet is to have it dry cleaned. Try to find a cleaner using less harsh, more eco-friendly methods if you can. Traditional solvents can be damaging to your woolens, as well as to the environment.

Although it may be tempting to put wool garments in the washer, don’t do it (unless the fabric has been specifically treated to make it machine washable). Even if it comes out looking fine the first time or the first ten times, felting is a cumulative process, and eventually it will start to change your fabric. Trust me, I know this from personal experience! Stick with washing methods that have a minimum of agitation and temperature changes, and you’ll be all set to care for your wool garment until it wears out—which could be decades from now!

The same wool fabric before (left), and after years of trips through the washing machine (right). Luckily, I was able to remodel this skirt so that I can still wear it.

As with any other fabric, make sure to clean wool the same way you plan to clean the finished garment before you cut into it. I often use the hand washing method above in the bathtub for big pieces of uncut fabric.

Wool has many advantages, but it also has some vulnerabilities, notably to clothes moths and carpet beetles, which have evolved to eat the protein in wool fibers. Clothes moths, which pose the greatest threat to wool garments, are tiny, golden, and hide from light. It’s the larvae—incredibly small grubs that hatch from eggs the moths lay—that actually eat the fibers. Although these moths are pretty much ubiquitous around the world, keeping them from eating your precious woolens is fairly simple. The moths don’t have time to complete their life cycle between normal washings, and they shy away from clothes that are out and about in air and light. You don’t need to worry about moths if you’re wearing and cleaning your woolens regularly. Be more careful when storing wool clothes for a while, such as putting them away during the summer months. Always store wool clean, since odors from oil and sweat attract moths. Store your garments in a container with a tight-fitting lid, and check to make sure it doesn’t have any holes that a tiny moth could crawl through. For long-term storage, it’s best if some air can get in but moths can’t. I store my wool clothes in a suitcase, with the zipper carefully closed, over the summer. If you do find moths, make sure to remove everything, especially other woolens, from the area, and clean everything thoroughly. Don’t use mothballs—they’re toxic to us as well as to moths. The easiest way to deal with clothes moths is to make sure they never get established—by keeping your garments clean and storing them carefully.

Wool and the Environment

Scottish Blackface sheep on the Isle of Skye. Photo by Caroline Granycome.

Wool is a natural, renewable resource. Just like any other resource, the impacts it generates on the environment, and the health of people and animals, depend greatly on how it’s produced. Sheep are very adaptable, and can thrive in landscapes that aren’t suitable for other crops or animals. Many of those landscapes also evolved along with some kind of grazing animals, so that the animals are now an integral part of the ecosystem. However, overgrazing can damage any landscape, and raising animals on a large scale presents other problems. Still, the biggest negative impacts on people and the planet from the production of wool fabrics almost certainly come from processing them, and the chemicals and dyes used, not from growing the wool itself.

For the past few years I’ve been trying to make more conscious choices in the fabrics I consume. I can tell you firsthand that fabric store employees usually don’t know where their wool fabrics are coming from or how they were processed. But at the same time, there’s been a recent explosion in the availability of small-farm, known-origin, minimally- and consciously-processed wool yarns for knitting, and I hope it won’t be long before the fabric world starts to catch up. A good place for us sewists to start is by asking questions: encouraging fabric sellers to get more information and be more transparent, and letting your local wool producers know that you’d like some fabrics to work with as well as yarns.

I hope you’ve enjoyed reading a little bit about the world of wool, and that you’ll be inspired to include some wool fabrics in your upcoming sewing. I’m pretty sure you’ll be happy with both the sewing and the results!

Author's note

Since I finished this article, I’ve continued my research into sustainable fabrics. I now have a small amount of two amazing wool fabrics to share! They’re made from Columbia wool sustainably raised in Oregon by Imperial Stock Ranch, and 100% processed and milled in America. I'm so excited about this, and about the possibility of making more fabrics like these available to sewists! The more interest and feedback I can get on this project, the better chance it has of becoming a reality. You can read more about the story of the fabric on my blog and check out the fabrics in my Etsy shop. I feel like we are on the cusp of a movement to make more intentional fabric choices available, and I’m thrilled to be a part of it!