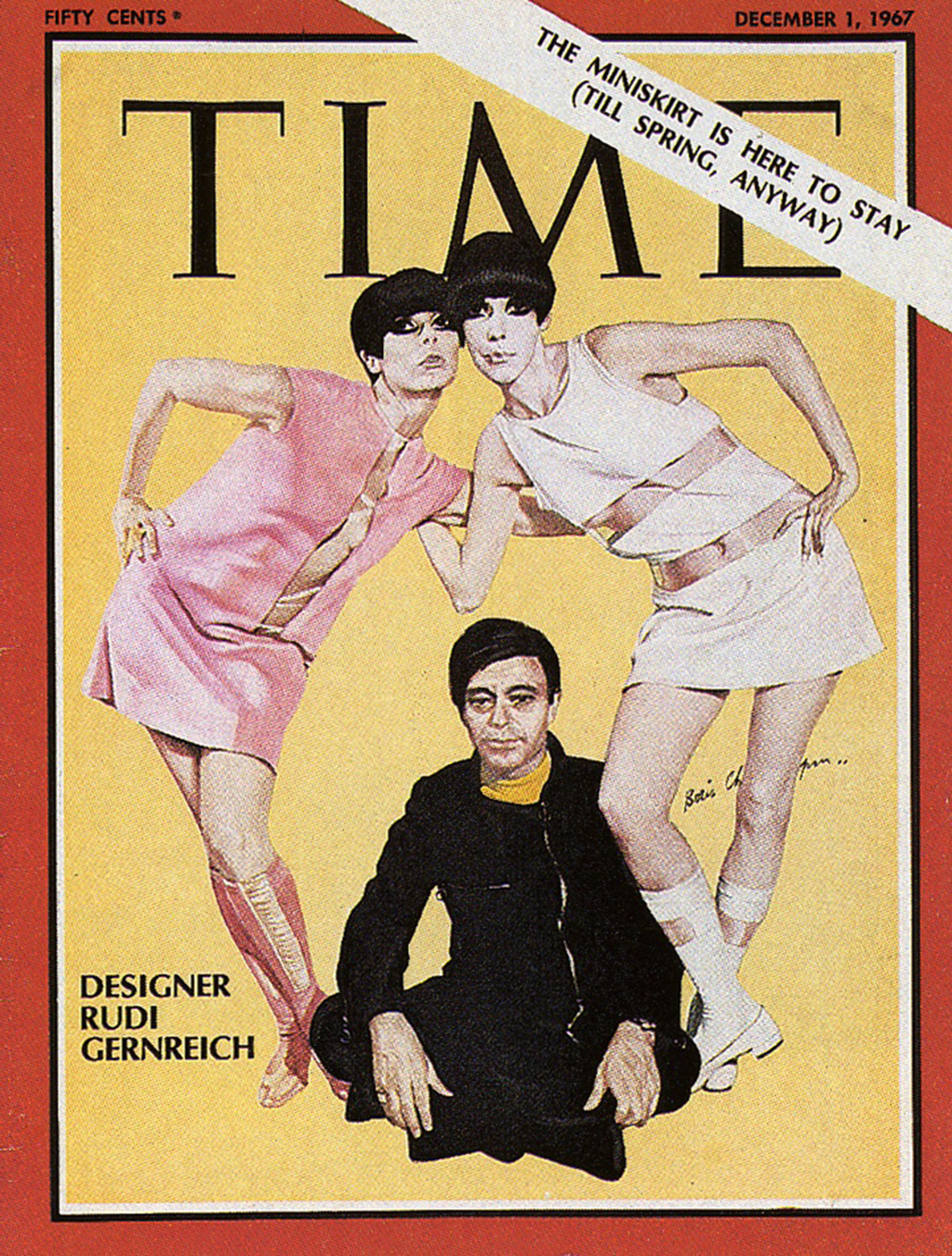

It was the 1960s, that revolutionary decade. In the midst of war, political upheaval, women’s liberation, and rock ’n’ roll, an unlikely man appeared on the cover of Time magazine in December of 1967. Fashion designer Rudi Gernreich sits cross-legged in a black minimalist suit with an offset zipper feature, while models Peggy Moffitt and Leon Bing dance above him in pastel knit dresses with contrasting transparent vinyl inserts. Not only were the women wearing the highly fashionable new miniskirts, but they were also doing so with no visible undergarments, as the clear vinyl quite obviously showed.

Rudi Gernreich’s Time cover, December 1967.

While designers such as Andre Courrèges and Paco Rabanne were inspired by a space-age view of the future, creating designs that incorporated spacey influences like vinyl boots, silver lamé, and astronaut-helmet-like hats, Gernreich was more inspired by a future that included true equality between men and women. His prophetic fashion statements earned him the title of “the most way-out, far-ahead designer in the US” in his Time article.

While his name is unknown by many today, he was—in his time—not only a media darling who created some of the most well-known styles of the 1960s, but a pioneering designer who changed the fashion landscape for decades to come.

The Early Years

Rudi Gernreich’s fashion instinct came naturally. Growing up in Vienna, Austria, Gernreich spent much of his young life in the salon of his aunt’s dress shop, learning about fabrics and sketching designs for the clientele. In 1938 Gernreich and his mother fled from Austria as Jewish refugees when the Nazis annexed the country. The family settled in Los Angeles where 16-year-old Gernreich found a job washing bodies at a hospital morgue.

Though Gernreich studied art and apprenticed at a clothing manufacturer, he grew increasingly disillusioned with the world of fashion. In 1942, after witnessing a dance performance by Martha Graham, Gernreich eschewed his art studies at the Los Angeles City College to devote himself to dance.

In California, the modern dance movement was being led by Lester Horton, who was gaining notoriety for his choreography that emphasized unrestricted movement and a whole body, anatomical approach to dance. Gernreich joined the Lester Horton Dancers for six years, dancing with them until 1949. Of his time with the company Gernreich said, “I was never a great dancer, but being with the company impressed me with the importance of the clothes in motion, body freedom, rhythm, attitude...and gave me a chance to design costumes.”

In the early 1950s, fashion was ruled by Paris. Styles were dictated by the couture designers, and everything from gowns to swimwear was, at best, influenced and, at worst, directly copied from the French runways. For Gernreich, who moved to New York to continue his career in fashion, the conservative atmosphere was stifling. “Everyone with a degree of talent—designer, retailer, editor—was motivated by a level of high taste and unquestioned loyalty to Paris [...] After about six months I began to vomit every time I thought about the imperiousness of it all.”

For women, the prevailing fashions of the day were physically restrictive. The New Look full skirts and fitted jackets that had been introduced by Dior in 1947 came complete with a complicated girdle structure that allowed little room for movement. Ready-to-wear garments may not have come with built-in shapewear, but the fashionable woman could supplement her shape with girdles, corsets, and bullet bras. Gernreich’s education in modern dance convinced him that women’s bodies should be freed from the constrictions of fashion—an idea that wasn’t welcomed in most garment companies. His inability to conform to mainstream fashion had him pinballing from job to job, until he started designing sportswear in the early 1950s.

Stretchy Swimwear

If you were off to the beach in the 1950s, you were most likely to zip on a one-piece sheath swimsuit, which would have likely included padded cups in the bust and corset-like boning through the waist. Flattering perhaps, but not exactly conducive to swimming. In 1952 Gernreich designed what would be the forerunner of popular swimwear for decades to come when he released the first bra-free swimsuit.

This unstructured tank was made of wool jersey. The body-conscious design moved with the wearer, allowing a freedom of movement previously unrealized for women. He followed this design with a new maillot style, which featured an elasticized wool knit that followed the body’s shape instead of pushing it into submission.

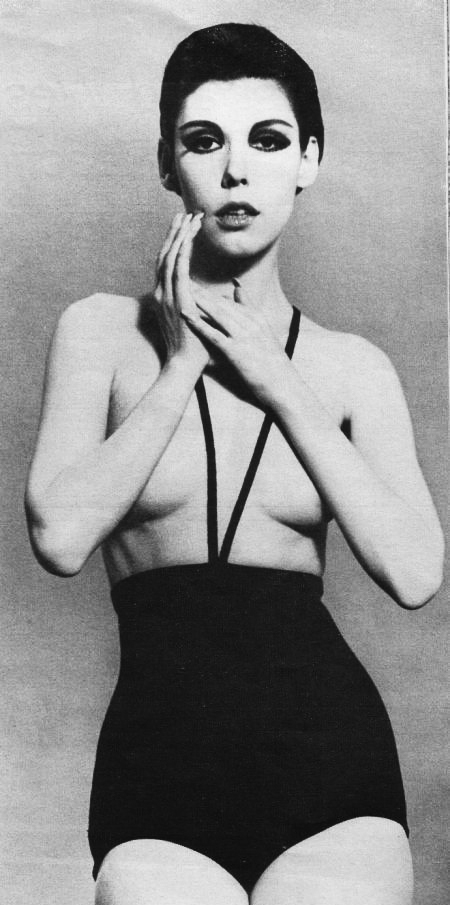

Peggy Moffitt modeling the monokini.

Even Sports Illustrated praised the new style, saying that Gernreich had “turned the dancer’s leotard into a swimsuit that frees the body. In the process, he has ripped out the boning and wiring that made American swimsuits seagoing corsets.” In 1956 his swimwear won him The American Sportswear Design Award as well as accolades from fashion’s elite, including Harper’s Bazaar’s Diana Vreeland.

While his unstructured swimwear brought him early notoriety, it was Gernreich’s 1964 bathing suit design—the monokini—that made him an international name. In the fall of 1962, Gernreich declared to Women’s Wear Daily and Sports Illustrated that, “the bosom will be uncovered within the next five years.”

Gernreich had been experimenting with cutouts in bathing suits when he was asked about the future of swimwear. As he later said, “I’d gone so far with swimwear cutouts that I decided the body itself—including breasts—could become an integral part of the suit’s design. Because of my Women’s Wear Daily statement, people began to ask me if I really meant what I said. The more they asked, the more I began to feel right about the idea.”

Two years later, a request from Look magazine propelled him to design the monokini. The suit featured a high-cut waist with a low, maillot-style bottom. It stayed on thanks to two thin strips that ran between the breasts to the back, acting as a halter. The bathing suit was featured—from the rear view—in the magazine, having been photographed on a prostitute in the Bahamas. When his muse, Peggy Moffitt, modeled the monokini in a photograph that ran in WWD, it was hailed by some as fashion’s future and denounced by the Vatican and outlawed in France.

“Freedom—in fashion as well as every other facet of life."

Rudi Gernreich on why he designed the monokini.

Though the monokini was initially designed as a statement to “cure our society of its sex hang up,” demand for it was so strong that it was put into production. Stores around the country begrudgingly ordered and sold the suit, however only two suits were known to be worn in public: One by Carol Doda, a stripper in San Francisco whose sporting of the swimsuit started the trend for topless bars, and the other by Toni Lee Shelley, a 19-year-old model in Chicago who wore it to the beach and was promptly arrested.

The Total Look

As youth culture gained momentum in the early 1960s, popular fashion started depending less on the fussy styles that were being sent down the runways in Paris and more on the minimalist lines and bright colors of designers like Mary Quant, Andre Courrèges, and Rudi Gernreich. Heavily influenced by the Space Race, designers started experimenting with different industrial fabrics. Vinyl and lurex were used in increasing amounts, as were throw-away materials such as paper and cardboard.

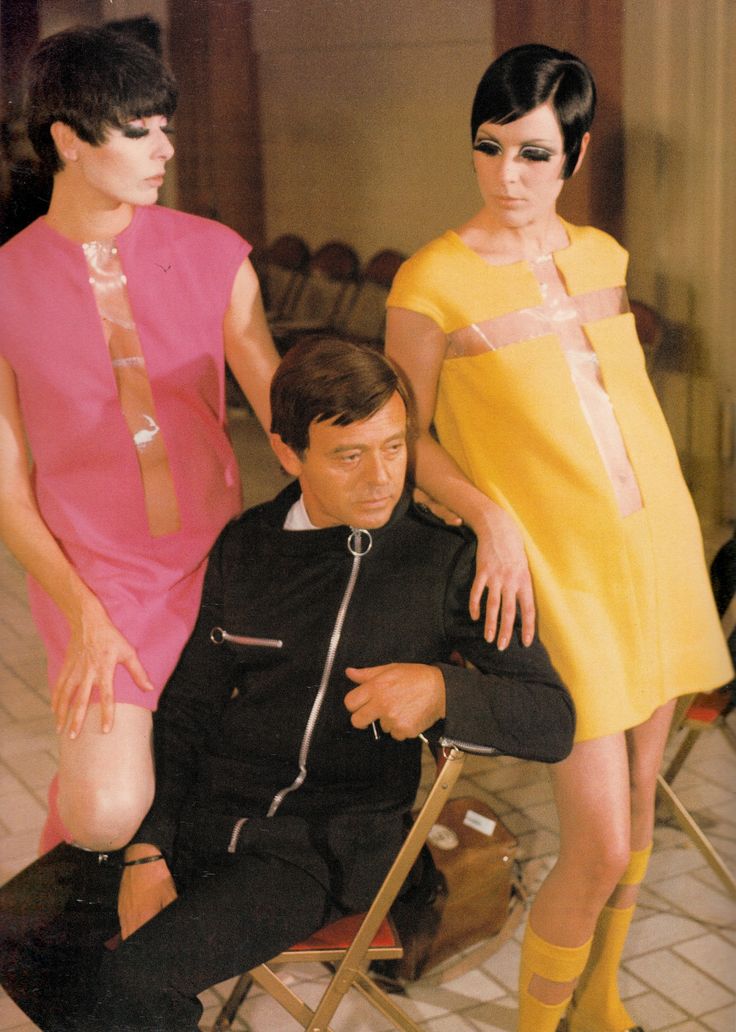

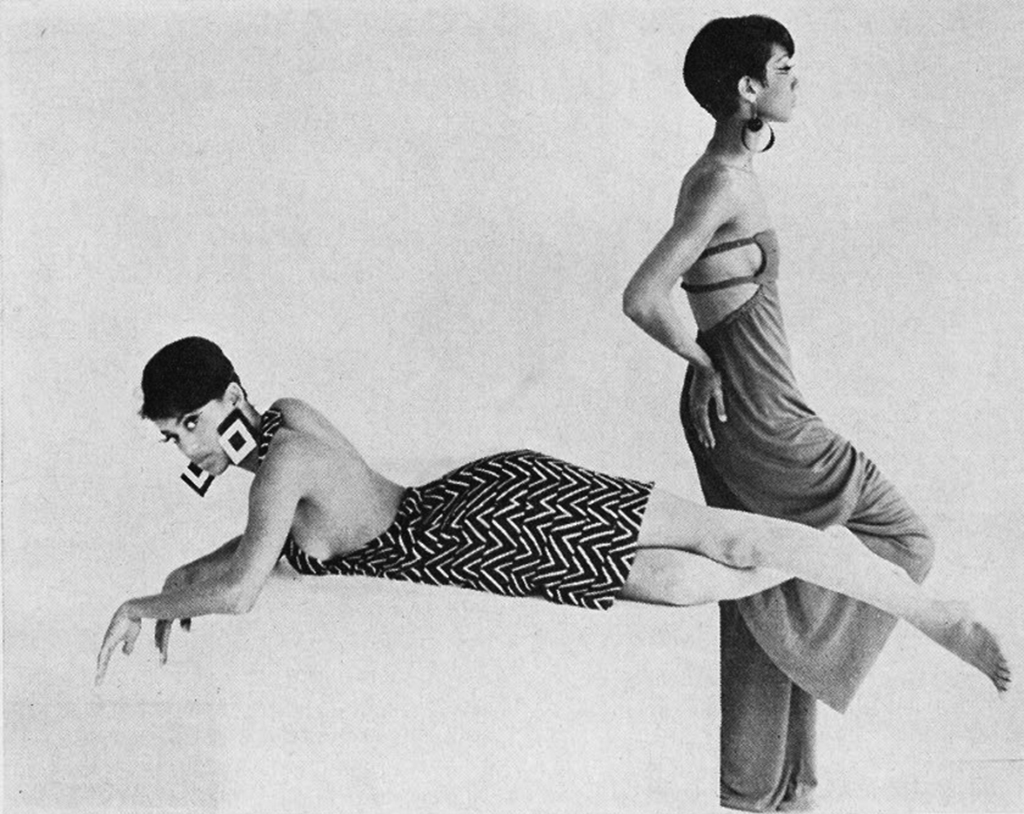

Gernreich with models. Gernreich was one of the first to

use zippers as design elements in garments.

Designers were not only exploring unusual materials, they were also using color in new, exciting ways. Gernreich, in particular, was noted for his vibrant color combinations. During his days as a dancer, Gernreich worked as a fabric designer and colorist at Hoffman Fabrics of California, designing textile prints and palettes. That early experience working with color served Gernreich well. His collections were full of interesting juxtapositions of shades—poison green and chocolate dresses, pink, saffron, and orange pantsuits, and lavender and red tops. He also played with neutrals, working with eye-catching black-and-white Op art prints.

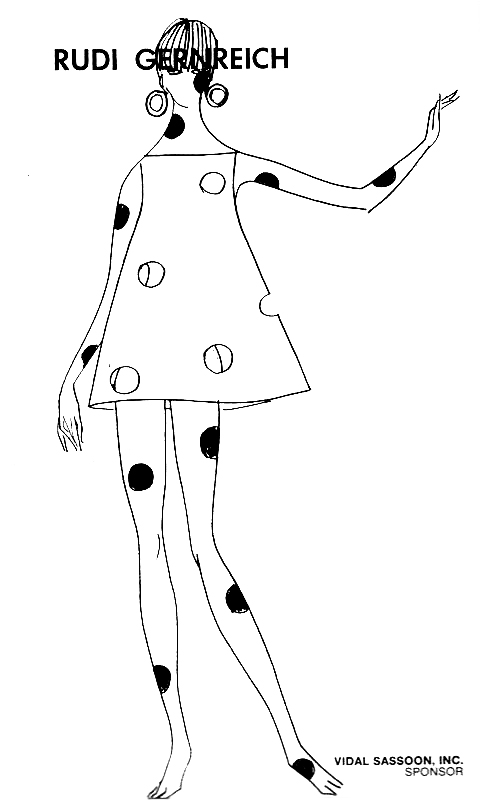

Peggy Moffitt modeling a

“total” Gernreich look.

Inspired by the Bauhaus art school’s philosophy of creating a total work of art, Gernreich promoted the “total look” with his clothing—his concept that all the elements of an ensemble should coordinate. An early total look outfit from 1964 paired a knee-length dress made with navy and cream vertical stripes with matching striped stockings. Two years later, in “Basic Black,” which is arguably the first fashion video, models appear in animal print coats, tights, hats and shoes. The coats are stripped off to reveal the matching dress, which is then itself removed to show the matching underpants and bras.

A Feminist Designer

As women’s roles evolved in society, many fashion designers were inspired to create collections for who they saw as women of the future—liberated working women who would no longer be constrained by fashion. In 1963, a full two years before Yves St. Laurent launched the Le Smoking tuxedo, Gernreich designed a white satin pantsuit he dubbed the Dietrich. He planned to show the suit during the acceptance show for his Coty Hall of Fame Award, when winning designers showed their recent collections. However, when Peggy Moffitt—with flat shoes and slicked-back hair—wore the suit during dress rehearsal, Coty jurors, unable to move past the stigma of a woman wearing pants, asked that Gernreich remove the suit from the show.

Gernreich persevered in his quest to free women from the shackles of confining undergarments by creating the no-bra bra. This revolutionary undergarment was made from two thin bias-cut triangles molded only with a small dart—no boning, no torpedos, no padding. The no-bra bra was made to support and celebrate the shape of the breast, without molding it into an unnatural form. The bra became an instant bestseller and changed the shape of intimate apparel, as well as the shape of women's clothing.

“The Bare Look" magazine layout from the July 1966 issue of Ebony.

As the decade progressed, Gernreich became increasingly interested in the concept of androgyny. In response to Life magazine's question on what men and women would be wearing in 1980, Gernreich predicted a time when "fashion will go out of fashion" and clothing will no longer be identified as male or female. Gernreich illustrated this principle with two models, a man and a woman, shaved totally hairless, wearing unisex outfits. Always trying to emancipate society from its sexual hangups, he proposed a future where there wouldn't be any squeamishness about nudity, and both sexes would go around bare chested, though women would wear protective pasties. In 1974, in response to a ban on nude swimming in Los Angeles, Gernreich designed a unisex bathing suit that adhered to the new modesty laws while still exposing the majority of the wearer, which he named and patented the thong.

“Prior to the sixties, clothes were clothes. Nothing else. Then, when they started coming from the streets, I realized you could say things with clothes. Design was not enough.”

A Design Legacy

Glance at Rudi Gernreich’s work and you will see quintessential 60s— bright colors, and mod, minimalist shapes. What you don’t necessarily see is the underlying goal of his designs—to free women and society from the constriction of fashion. Gernreich was one of the few designers who didn’t just use his talent to dress women, but also used his art as social commentary. In doing so, he left a legacy of design that has, as director and chief curator of the Museum at FIT, Valerie Steele, said, become “So thoroughly assimilated into the fashion vocabulary that people don’t think to credit him. His designs are so accepted that designers don’t know that they originated with him.” Gernreich was the first to make a soft bra, the first to design a knit tube dress and knit leggings, the first to promote androgynous dressing, and of course, the first to think of the thong.

Gernreich’s name will never be as recognizable as Chanel, Dior, or any of the other international fashion giants. However, fashion is always—even if unknowingly—paying homage. Every time a see-through blouse walks down the runway, or a miniskirt is paired with patterned tights, that is a nod to Rudi Gernreich.

As New York Times fashion reporter Bernadine Morris said, “Gernreich’s big contribution wasn’t the cut of a sleeve or a particular color, or any of those dressmaking details so dear to the hearts of fashion people who love to return to the good old days which they understood so well. It was a brave new sweeping concept—that clothes should be comfortable. And just the tiniest bit fun to wear.”