The fast fashion industry is a behemoth, and growing. Built on the backs of garment workers, enabled by capitalism, fast fashion spits out lightning fast micro-trends while—to justify incredibly low prices—asserts that there is such a thing as “unskilled work,” not worthy of a living wage.

Over the last years, many consumers have insisted on more transparency from the industry, calling for a reckoning that is slow to come. But the colossal size of the fast fashion industry generates a huge amount of momentum, making individual action seem almost laughably inconsequential.

As people have become aware of where their clothes come from, more and more push for fashion industry workplace improvements. But the going is slow, and these improvements are often only spurned on after horrific and preventable tragedies—tragedies that are usually foreseeable.

Before I speak of radicalizing your sewing practice, here are just a few examples of the harm caused by the myth of unskilled labor in fast fashion.

Treatment of Garment Workers Throughout History

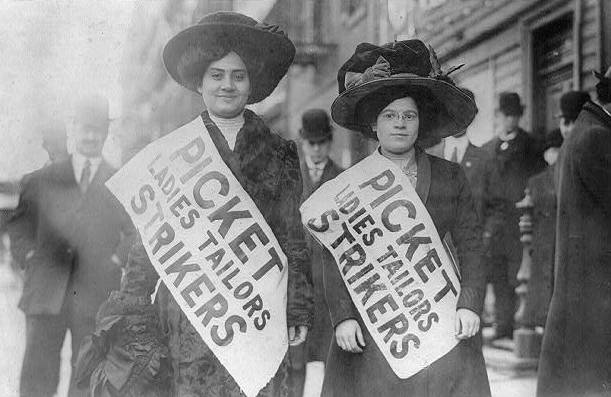

The New York shirtwaist strike of 1909 gained momentum because it had foresight; it anticipated tragedies that were to come. Largely made up of women immigrant workers, it was lead by Clara Lemlich, who spoke in her native Yiddish to her fellow workers, rallying more than 20,000 strikers and eventually leading to increased wages and shorter work weeks (though many of the safety concerns raised by the strikers went unaddressed). The strike was certainly a victory and a step forward for garment workers. Still, it was followed only two years later by the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in 1911, wherein 146 garment workers lost their lives to fire. They were trapped behind doors locked by the building owners to prevent unauthorized breaks, in blatant disregard for their employees’ safety.

Some marginal workplace reform followed the fire, and United States legislation continued to slowly improve conditions over the following decades, but even today, reports of domestic garment factory conditions continue to paint a picture of exploitative pay, poor conditions, and long hours for many. Capitalism and a consumerist culture demand more, now, and while U.S. garment factories are far from perfect, the same system that allowed the poor conditions leading to the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire continued to thrive elsewhere.

One hundred years removed from the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, the 2013 Dhaka garment factory collapse followed a hauntingly similar outline—poor regulation, owners with a disregard for their employees’ safety. Despite the building being declared structurally unsound, workers were ordered to return to work. That same day, the building collapsed, taking a staggering 1,134 lives with it. The resulting legislative and industry action has been slow and widely criticized. Still, there are accounts of harassment and poverty wages, and many workers report being unable to leave their current positions because nothing better is available.

The Myth of Unskilled Labor

Capitalism perpetuates the myth that there is such a thing as “unskilled labor.” How else could poverty wages be justified? Many garment workers have been honing their craft for years, often being paid a too-low piece rate that fails to amount to a livable wage and penalizes employees for mistakes or breaks. These are people who’ve often spent years or decades in clothing construction, honing their technical skill to a high level. A person need only sew a single garment before realizing the price fast fashion companies charge for their product is staggeringly, unsustainably low.

This is a systemic problem. A systemic problem requires a systemic solution—the burden of fixing the system does not fall on the individual consumer.

This is a systemic problem. A systemic problem requires a systemic solution—the burden of fixing the system does not fall on the individual consumer who, often, is also fighting for their own financial security. Among the complicated solutions to an oppressive worldwide supply chain lies the knowledge that we all are, in effect, victims of capitalism. But if there is any hope for change, it’s important to resist allowing this sentiment to breed apathy.

It is virtually impossible to live in a capitalist society without participating in capitalism, and refusal to participate in the fast fashion industry is only possible with a fair amount of economic privilege. Many people who would like to avoid buying into the fast fashion industry are unable to do so by no fault of their own. It is hugely frustrating to see one’s place in the machine and yet be unable to leave. In an economic landscape that devalues handcraft and slow making, your own home sewing practice can serve as anti-capitalist protest, bridging the gap between physical needs and personal values.

Sewing as Anti-Capitalist Protest

I am not proposing that every person on Earth sews themselves every garment they will ever place on their body; rather, I am encouraging sewists to be gentle with themselves as victims of an oppressive system, while taking on what they are able for the benefit of those with less privilege. Mending those pants or slowly constructing a handmade top is one drop less in the leaking and precarious bucket on garment workers’ shoulders. When making is unavailable, purchasing secondhand or from companies who view their workers as people first—not cheap labor—helps nudge the industry in a more ethical direction. While I am forced to participate in capitalism, I aim to do so with as little harm to others as possible. And so, I sew.

While I am forced to participate in capitalism, I aim to do so with as little harm to others as possible. And so, I sew.

Furthermore, refusing to monetize a hobby is inherently anti-capitalist. Pursuing a hobby takes privilege, yes, but it also takes a huge amount of determination to carve out personal time in our high-pressure, high-velocity culture. Capitalism compels people to monetize their time, their talents, their joys, often rewarded only with small returns exhausting burnout. By participating in a hobby for your own joy you reclaim your time and refuse to feed into the more, more, more mindset. In this way, cultivating free time is radical. It is the mark of an intentional life. Sewing not only brings my life more in line with my personal values and allows me to participate in the larger fashion dialogue in a more ethical way, it is also a cherished creative outlet.

Globally there is work to be done. Systemic change comes to pass through prolonged activism and intentional legislation. To make this work non-performative, it must be integrated into our very way of interfacing with the world, into our daily lives, informing our actions. Sewing—and so much of individual action—is not a distraction from this work, but a way to incorporate this driving ethos into daily life.