“To the Yoruba, the purpose of an item is sometimes more important than the item itself.”

I got my first Aso-ebi at ten years old. My mother came home with 20 yards of Ankara fabric and said, “Right everyone, we have a family party. Find a style, and get yourselves to my seamstress—you have two weeks and three yards each.” My cousins and I spent the next two days poring over pattern catalogs, looking for a unique style.

Wherever Africans or people of African heritage gather to celebrate, you’ll be sure to see people wearing brightly colored fabric, sewn into beautiful styles—you’ll see men, women, and children wearing the same colors, sometimes the same fabric, proudly blending together and rocking to Afro-beats. An onlooker might say: why is everyone dressed the same? Anyone in the know would say Aso-ebi.

What is Aso-ebi?

Aso-ebi originates from the Yoruba, a tribe of South Western Nigeria. We’re found pretty much everywhere. We have a love of fashion, fabric, and food. We believe our Jollof rice is the best—a story for another day.

A literal translation of Aso-ebi would be “family cloth.” It is a practice in which a group of people uses the same pattern or color of fabric to make an outfit that denotes association. Nigerians love a great party, both throwing and attending. After setting the date, the next most important item is Aso-ebi.

Custom dictates that the celebrants decide the color, quality, quantity, and cost of the fabric, depending on the occasion. It is then up to you, the attendee, to pay for your fabric, choose a design, and get it sewn for the event.

An onlooker might say: why is everyone dressed the same? Anyone in the know would say Aso-ebi.

A Brief History of Aso-eb

Contrary to what some history books tell us, fabric and fashion have always been an important part of life in most African communities. Social historians believe that the Yoruba have been wearing Aso-ebi since the early 15th century.

Everyday fabrics were once made from flax, jute, or hemp yarn woven into coarse linen. For special occasions (like the crowning of a new king), strands from the cocoon of the Anaphe moth were spun to make raw silk.

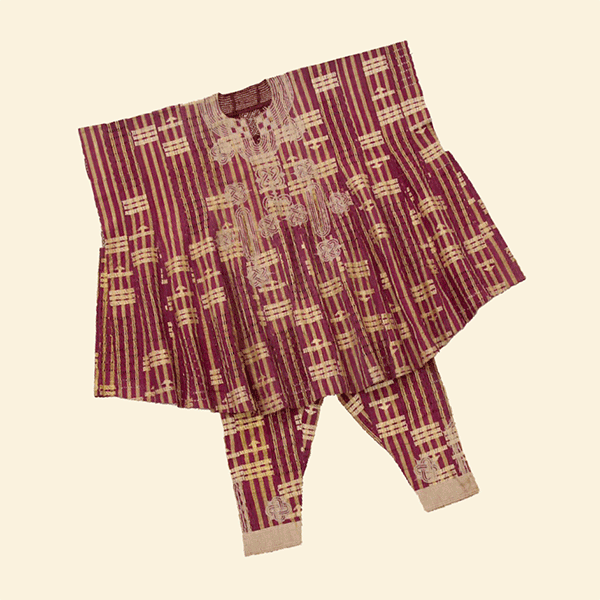

Most Nigerian communities have their own way of weaving fabric; the Yoruba are known for Aso-oke. The weavers were concentrated in the hilly areas of Yoruba land—consequently, the finished pieces of fabric were coined cloth from the hills.

Weaving used to be the livelihood of entire families. Men used three-meter horizontal looms that snaked their way up the hilly terrain, whilst the women used vertical looms that could be propped against a wall and covered during the day.

Everyday fabrics were once made from flax, jute, or hemp yarn woven into coarse linen. For special occasions (like the crowning of a new king), strands from the cocoon of the Anaphe moth were spun to make raw silk.

Most Nigerian communities have their own way of weaving fabric; the Yoruba are known for Aso-oke. The weavers were concentrated in the hilly areas of Yoruba land—consequently, the finished pieces of fabric were coined cloth from the hills.

Weaving used to be the livelihood of entire families. Men used three-meter horizontal looms that snaked their way up the hilly terrain, whilst the women used vertical looms that could be propped against a wall and covered during the day.

As a child, I often wondered why a fabric known locally as Indian madras was popular amongst the people of Eastern Nigeria—it is similar in design to locally woven fabric known as Akwete. Akwete patterns range from plain plaid to motifs that signify royalty, class, and family.

You’ll find Indian madras in Nigeria because the use of imported fabrics coincided with the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. Slavers brought cotton cloth from India and Europe in exchange for enslaved people that were eventually transported to the Americas and the Caribbean. Africans who acted as middlemen would ask for different types of fabric, based on the fashions of the time. Some of those fabrics are still in use today.

Aso-ebi at Social Events: From Weddings to Funerals

Some believe that Aso-ebi started at funerals of highly-placed individuals and town leaders. The deceased's siblings and children wore Aso-ebi so that mourners could identify them and pay their respects.

Aso-oke used to be reserved for weddings and funerals. As people got richer, Aso-oke found its way to other celebrations and became de rigueur for Aso-ebi.

For weddings, women traditionally wore a large piece of material wrapped around the waist (the wrapper), a blouse made of white or cream fabric, and a head-tie from the same material as the wrapper. My mum's wedding Aso-oke is made of wild silk and dyed cotton yarn. I’ve transformed it from a traditional wedding wrapper to a smart suit.

Anthropologist William Bascom suggested that Aso-ebi became widespread after World War I as soldiers returned home with money and fabric. He says veterans wore "uniform" clothing at kinship meetings known as Egbe. Women followed suit and wore the same color of head-tie or blouse with a wrapper at social events. At the end of each meeting, the chairperson specified the color to be worn at the next event. It is a practice that continues with most ladies’ and men's groups today.

When my mother chaired her ladies’ group, 12-year-old me would be given the last-minute task of writing the agenda in my best handwriting, before the Ladybirds women's group descended in their finery—all in Aso-ebi, outdoing each other with the size of their head-ties and matching accessories. After a few minutes of admiring each other, they’d all kick off their shoes and place their elaborate head-ties on the side, a quick prayer, and the meeting began.

Our Love of Fabric: Batik, Tie-dye, and Lace

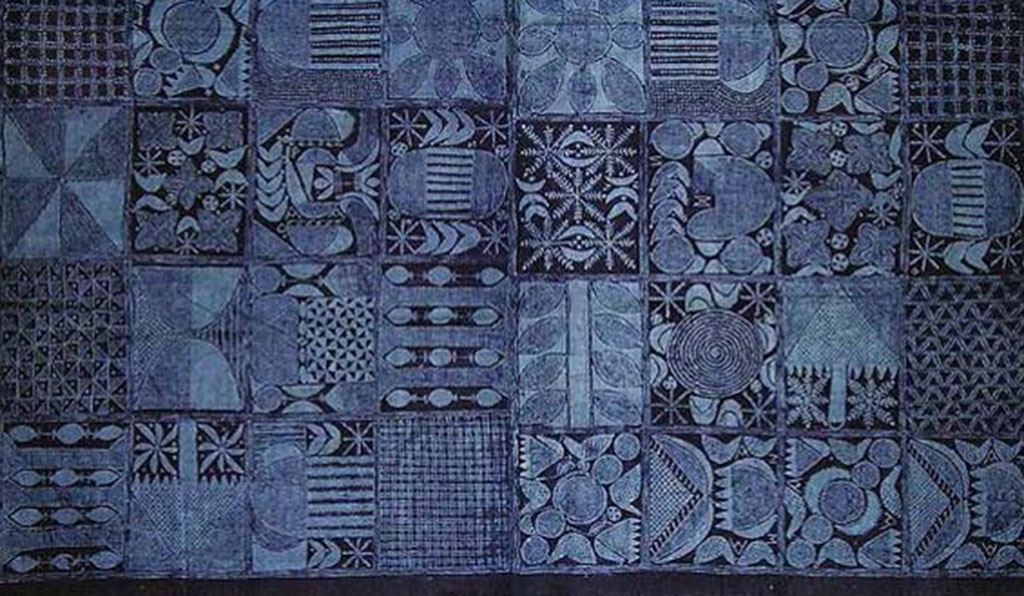

For some occasions, families would use the tie-dye or batik fabric known as Adire. The fabric would be tied and dyed with henna, indigo, and other plant dyes. For the batik, motifs representing the family or artist were transferred to the fabric—either by hand or a metal stamp and starch paste. Wax has replaced starch paste, and a variety of synthetic dyes have brought Adire to the masses. Today, Adire has taken a back seat, and the Dutch wax print material known as Ankara has taken over.

An integral part of Aso-ebi is a wonderful fabric called lace. West African "lace" is known as industrial embroidery by manufacturers. It includes fabrics such as Guipure (chemical lace) and eyelet embroidery. Originally manufactured in Italy, Austria, and Switzerland, it has been adapted for the West African market and is sold in sets of 5 or 10 yards.

Nigerian women’s love affair with embroidered fabric began in the early 1930s. Women in the West wore white embroidered blouses with Aso-oke, and those in the East complemented theirs with Akwete, and sari fabrics known as "George." Aso-oke became popular in the 1960s, as people had more money and more time for celebrations.

Imported fabrics that mimicked the eyelets, perforations, and colors used in Aso-oke became more popular as people were too impatient to wait for the handwoven fabric. The copycat fabric was lighter, easier to wear, and could be worn for any occasion.

Change to keep Aso-ebi on one line

I make my Aso-ebi outfits, and each outfit is a one-week project. First, I decide on style—maxi dress or traditional blouse and wrapper. I get inspiration from BellaNaija and Pinterest. I adapt my Seamwork patterns and follow other makers on YouTube. Making a muslin is a must, as making a mess out of expensive fabric is heartbreaking. Happy with the muslin, I measure and re-measure, cross my fingers, cut and sew.

What do I do with the Aso-ebi outfits clogging up my wardrobe? I re-purpose them into tops for myself and my girls. From Aso-oke I make lovely cushions for friends and family.

Historically Aso-ebi was a unifier, but it has begun to create divides based on money and social class, and some members of younger generations are questioning its role.

With a global pandemic still raging, Aso-ebi has now taken a back seat. We are all mourning the loss of some traditions: music gigs, Eid prayers, church, and the ubiquitous parties with regulation Aso-ebi. Unfortunately, a Zoom party with Aso-ebi is not the same. I asked a few friends whether they have missed Aso-ebi. All said "No!"

We all have beliefs and behaviors passed from generation to generation—traditions that keep us grounded, give us something or someone to connect with. They help us realize that we are part of something bigger than ourselves—you could call it community, or culture. Aso-ebi acts as a uniform blurring the socio-economic divide. Depending on your creativity or flair for fashion, these divides are less noticeable when everyone is dressed in the same fabric.

When considering the future of Aso-ebi, my question is: How do we come back stronger and more cohesive, wearing what we can to belong and not being constrained by Aso-ebi?