It’s 7:30 in the morning on a Wednesday in July, and I’m sitting in the cool quiet of the downstairs, absentmindedly gathering supplies to mend a hole in the knee of a small pair of woolen leggings. Everyone else in the house is asleep. The sun is still soft, and after a hard night of rain, the garden outside is steaming and swirling with mist. Holding a wooden darning egg, I stretch my first set of stitches across the hole. Using techniques gleaned from photos on Instagram and YouTube videos, I carefully fill the gash torn by little girl exuberance with a small patch of woven reinforcement. Over under over under over under. I pick up my phone to scroll through saved posts for a reminder of stitch spacing and pause on an image in the archive: a photo of a Black woman knitting.

The photo is uncredited, but the dress suggests some time between 1900 and 1920. She looks serene and capable, and I am reminded of my grandmother, Mary Burns—a woman who, by all accounts, was extremely capable and hardworking, but (for a host of complicated reasons) I never met. According to my father, she could sew, upholster furniture, and even wire a cabin for electricity. Born in Arkansas in 1920 as a descendent of enslaved Africans, she valued self-sufficiency and handwork. I’d wager she could have taught me to mend this hole, neatly repairing the damage in this small and well-used pair of winter woolens.

From YouTube to Instagram to personal blogs and online tutorials, I’m grateful that so many women all over the world are sharing these skills with me. However, I’m also filled with grief that my origin story as a maker is full of familial holes.

The next photo in the feed is a black and white photo of a woman weaving on a Hausa Loom in Northern Nigeria, the country that accounts for my largest cohesive group of genetic markers. Weaving is yet another skill I learned through online tutorials and library books. I watch white hands on a tiny screen pull fiber through heddle slots of a loom. There were weavers stolen from Africa as well as seamstresses and farmers and builders, and they brought that knowledge with them.

As I move through my day: venturing into the garden to check on my seed saving, slicing a paper bodice pattern piece open to add bust ease, pulling a shuttle loaded with linen through the shed of my loom, every single reference I have for learning is made by white makers.

It’s the afternoon now; the sun has burned away the garden mist, and I’m filling a wooden bowl with zucchini and basil leaves. A neighbor who I don’t know very well pauses to say hi and asks me where I learned to do “all of this.”

“Here and there.” I shrug and wipe my hands on the apron made of linen scraps that I’ve tied around my belly. My grandfather was born into a sharecropping community in Mississippi, and I am learning to save seeds from video clips of a white gardener in England.

On Instagram, a Black knitter recounts a story of knitting in a waiting room and being told by a white woman that she didn’t know “Blacks” knit.

Old Washington Post articles keep me company while I wait for the pasta water to boil. A piece from 2019 details how Jackie Kennedy snubbed Black couturier Ann Lowe after she designed the First Lady’s wedding dress. She was described at the time simply as “a colored dressmaker.” One of the most significant looks worn by one of the most famous American fashion icons was scrubbed of its color by the careful revision of history. Generations of women have sat down to leaf through fashion magazines and pattern catalogs, amassing inspiration for their own special sewing projects and style. They drew inspiration from white icons: Marilyn, Jackie O, Audrey Hepburn.

There are plenty of white makers who have been severed from their own family's maker roots, but they are reflected in the narrative of historical American craft in ways that I have never been—a public legacy where the private legacy has been obscured. I turn to load the dishwasher and wonder what portion of the very foundation of modern style was invented and made by invisible Black women.

I turn to load the dishwasher and wonder what portion of the very foundation of modern style was invented and made by invisible Black women.

After dinner, I’m at the sewing machine pulling linen through my ancient featherweight. My oldest has had another growth spurt and needs shorts. She's reached an age where she is beginning to realize the work that goes into creating the life she lives. The handmade clothing, the home-baked bread, the handknit sweaters. Sitting on the floor rearranging my spools of thread, she asks:

"Who taught you to sew, mom?”

"YouTube.”

In the background, we listen together as the woman on a baking show describes learning to bake by watching her grandmother.

"Who taught you to make bread, mom?"

"I read a blog.”

My youngest walks in to join us, trailing tiny scraps of paper from her latest attempt at free-form paper doll drafting. I used to love paper dolls; they were out of fashion by the time I was born, but past eras of making and a daily life lived to the rhythm of handwork has always appealed to me.

It's time to start teaching my girls how to bake bread, knit scarves, sew a French seam, and clip an armhole. There is useful knowledge that has been handed down to me, perhaps most importantly, an instinct for self-preservation and survival.

I do not see myself reflected in the legacy and story of American craft, and it makes my qualifications for handing this knowledge down feel borrowed and shallow. The loss is heavy; it presses on me firmly as I iron the hem of her new shorts. My daily life: baking, cooking, sewing, knitting, mending, gardening, canning, and weaving is disconnected from those that came before me.

My mother taught me to make space for softness in a hard world and the value of making. However, many of my daily activities have no direct line back through the generations on either side. I am not baking bread from a recipe handed down; the skirt I'm wearing was sewn together using techniques picked up from strangers. My oldest asks, "What do you think I should know by the time I'm a grown-up?" She's asking for a list of my most cherished practical skills, waiting patiently as I measure around her middle for the elastic waist.

I do not see myself reflected in the legacy and story of American craft, and it makes my qualifications for handing this knowledge down feel borrowed and shallow. The loss is heavy; it presses on me firmly as I iron the hem of her new shorts. My daily life: baking, cooking, sewing, knitting, mending, gardening, canning, and weaving is disconnected from those that came before me.

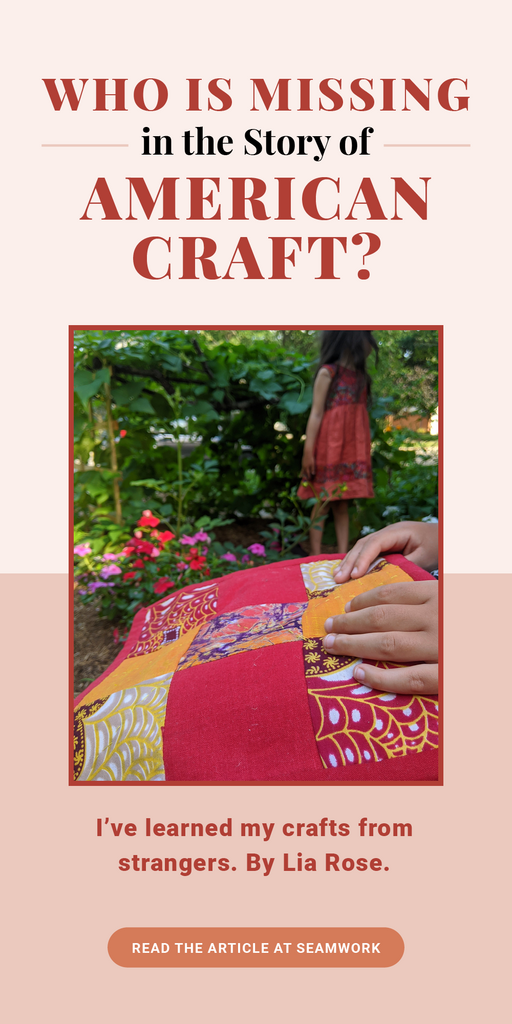

My daughter squeezes herself in beside me at the sewing machine as I begin to thread the new color, her little hands resting next to mine. I am struck by the pulse point on each of our wrists, side by side, carrying blood. Blood cannot be easily obscured, and it cannot be stolen.

The blood in my veins was given to me by those that came before me, and while my grandmother was unable to pass on her skills to me directly, it is her blood singing inside of me when I turn to my daughter to share the list of important practical skills that I will teach her.