Roughly 15% of the total fabric used by the fashion industry is wasted, which this is just one of the many ways that fast fashion negatively impacts the environment. To counteract these wasteful practices, a new movement, zero-waste fashion, has sprung up. Zero-waste garments are produced with little or no textile waste. How is this possible? Most patterns that sewists encounter include curved seams and hems, as well as multiple pieces that flare at different angles, making it impossible to create a cutting layout that generates no scraps. Yet an entire cadre of designers, many with their own labels, has embraced this challenge, and is creating distinctive, fashion-forward clothes.

In the coming months, we'll dive into the basics of zero-waste fashion. This article will focus on zero-waste fashion design, or the process of designing garments whose pattern pieces generate no waste. The second article in the series will look at ways of eliminating waste after the original garment has been stitched (called post-consumer zero-waste fashion, to distinguish it from zero-waste strategies that eliminate waste before consumers enter the equation). The final article will look at innovative ways of manufacturing clothes that create zero fabric scraps.

Zero-Waste Design

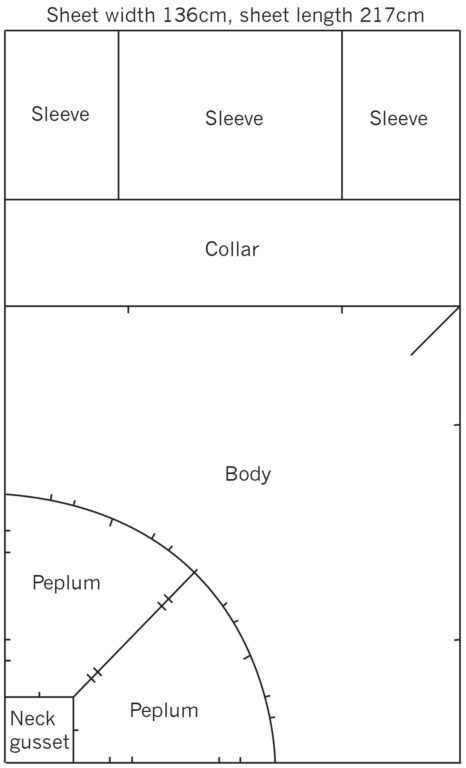

Zero-waste design patterns often include clever fabric manipulations

and cutting layouts. Courtesy of Timo Rissanen.

The pattern pieces of a zero-waste design fit together such that no fabric is wasted during the cutting phase. In practice, this can mean eliminating the odd spaces between pattern pieces, designing pattern pieces that interlock like puzzle pieces, or creatively using up leftover bits of fabric to make embellishments, bias tape, and the like. Other designers create shape by removing fabric, usually starting with a flat piece and then slicing it open with a strategic set of holes that allow the material to be twisted or fed upon itself, often producing garments that can be worn in more than one way (think of the innovative draped Japanese patterns you’ve seen). The movement has been embraced internationally and includes designers such as the UK-based Mark Liu and Julian Roberts, New Zealand’s Holly McQuillan, as well as Yeohlee Teng and Timo Rissanen in the United States.

Although recently popularized as a response to fast fashion, zero-waste design has been around for centuries. It can be found in many traditional garments, like the Japanese kimono and the Indian sari. Back then fabric was dear and people minimized waste to maximize their fabric. Design elements often included gussets or gores, minimal arm shaping, rectangular sleeves or pants, and people engineered garment pieces to match the available fabric’s length and width.

As fabric became affordable and production became industrialized, waste crept into the manufacturing process. These days, a designer typically operates independent of the pattern maker, and both have little contact with those responsible for cutting layouts and garment manufacture. Thus many designers have little sense of how their designs affect pattern, grading, and layout, all of which, in turn, affect the amount of waste generated.

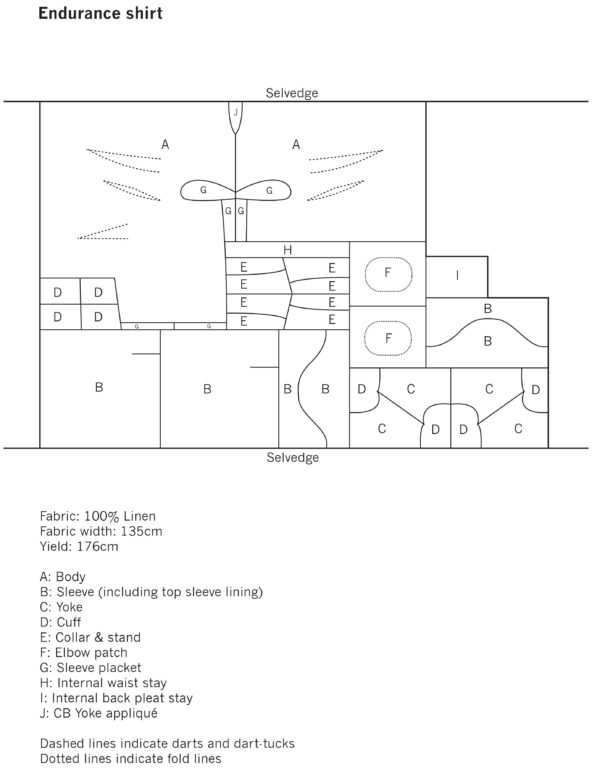

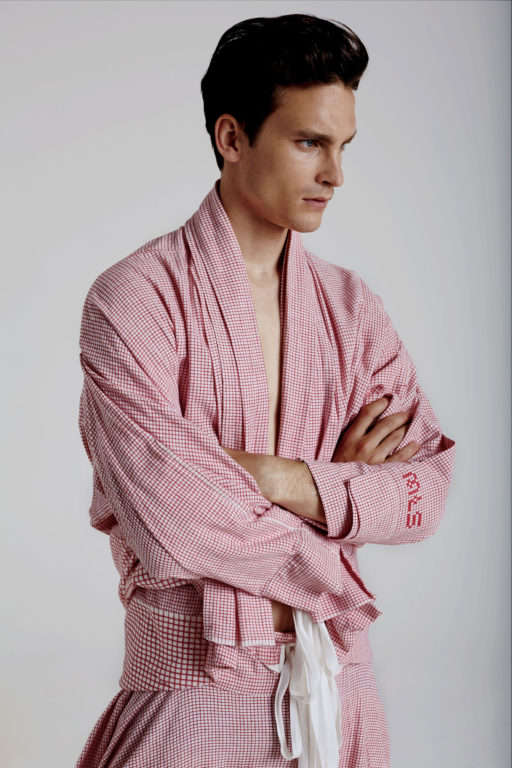

The above pattern was used to create this shirt.

Photo courtesy of Timo Rissanen.

Zero-waste design integrates these skills once more. Timo Rissanen, who teaches zero-waste design at Parsons the New School for Design and who is a leading innovator in zero-waste design, notes that “you have to bring the patternmaking and the cutting and the making into the design process.” Whereas many designers have little idea how a garment looks when its components are separated and laid flat, Rissanen says that “pattern is important for me because it’s key to eliminating fabric waste.”

Rissanen first became interested in the idea in 1999, when he wrote an undergraduate thesis that focused on the French designer Madeleine Vionnet, who later influenced Issey Miyake, John Galliano, and Claire McCardell. Vionnet’s innovative use of the bias properties of fabric, in which she considered both the width of the fabric and the grain, and her use of geometric shapes such as rectangles and quarter circles, led Rissanen to believe that it might be possible to design garments without wasting any fabric. “I think she ‘listened’ to the grain of the fabric more deeply than most designers, and that is what inspired me about her work,” says Rissanen.

Madeleine Vionnet

I realized that Vionnet had taken on a project that transcended any notion of a fashion season, and yet worked passionately in fashion, and that sense of commitment has stayed with me. -Timo Rissanen

Madeleine Vionnet was born in 1876 and first entered the fashion world as an apprentice to a dressmaker. By eighteen she had married, given birth (her baby died in infancy), and divorced her husband. Undeterred, she worked in Paris and London before opening her own house, first in 1912 and then again after World War I. Her designs were wildly popular with Americans and Europeans alike, and at her height she had over a thousand employees. When she retired in 1939, she had created over 12,000 garments.

Vionnet was known for her body-skimming bias cuts. She wanted to free women from the tyranny of the corset. She was also drawn to using the bias because its stretchability created garments that could be slipped over the head, anticipating the desire for ease and comfort that have made knits so popular today. Before Vionnet, bias cut fabrics were primarily used for collars, but she expanded the use of the bias to include the entire garment, and she created stunning gowns, blouses, and skirts as a result.

She sought to maximize design excellence while minimizing the amount of work involved. Her designs used the fewest seams or cuts possible, and she played with volume, shape, and fit by manipulating fabric and working with grainlines. Where other designers might use darts or curved pattern pieces, she frequently twisted bias-cut rectangles or half-circles at various spots in the bodice or waist to cinch in fullness while adding a decorative element. In this way, she laid the groundwork for much of the zero-waste design of the twenty-first century.

A contemporary of Chanel and Nell Donnelly, Vionnet had Chanel’s fearless vision and Donnelly’s commitment to her workers. Remembering her early days in the business, when she worked in poor lighting and sat on a stool until her eyes watered and back ached, Vionnet provided chairs with backs, an on-site physician and dental surgery, and a subsidized cafeteria. She was also a fierce opponent of copyright infringement, and instigated a number of protective practices that other couturiers soon adopted.

Inside Timo Rissanen’s Design Process

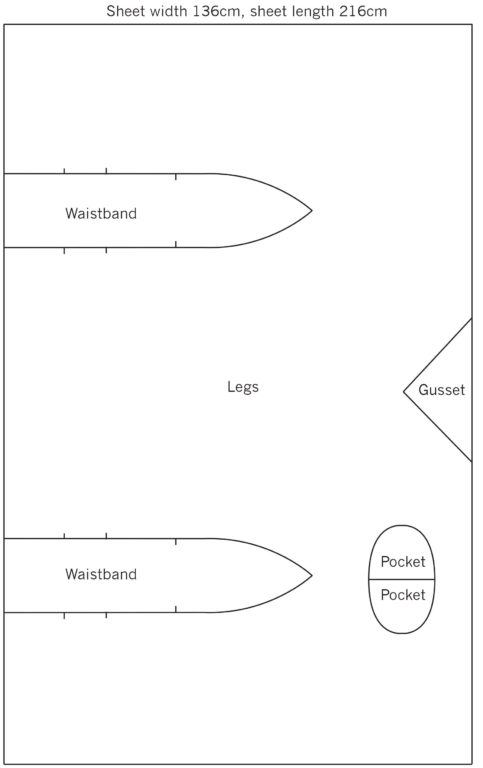

MLS Pajamas, created from two old bedsheets.

Photo courtesy of Timo Rissanen.

These days, Rissanen remains inspired by Vionnet, even as he continues to push the boundaries of zero-waste design. “Vionnet seemed to be endlessly fascinated by the possibilities created by the combination of fabric, the moving body, and gravity, and that is something that has stayed with me ever since I was a student,” he says.

To the uninitiated, zero-waste design layouts look intimidating. The finished pattern looks like intricate interlocking puzzle pieces that emerged, fully formed, from thin air. However, Rissanen emphasizes the design process is an iterative one. His first pattern, fittings, and alterations focus on garment shape. Once that works, he looks at the pattern pieces on the actual fabric width and begins designing the garment details, like the collar and cuffs for a shirt. “Essentially, I’m going from the largest pieces to smallest as the design process progresses.”

Courtesy of Timo Rissanen.

Courtesy of Timo Rissanen.

This process can vary by garment type. With womenswear he sometimes begins with the fabric itself and lets it guide his process, much as Vionnet listened to the grain of the fabric nearly 100 years ago. However, he finds that menswear tends to be more pattern-driven. The MLS pajamas, for example, were largely designed by folding many sheets of paper, as a letter-sized sheet was very close in proportion to the two old sheets that he used for the final garment.

Rissanen is quick to point out that design alone cannot solve the environmental, health, and social costs of fast fashion. The industry’s—and the global economic system’s—reliance on consumption is the heart of the problem. Consumers also have a role in increasing the industry’s sustainability. “Focus less on the clothes you want or need or think you should buy because they are ‘sustainable,’ and more on who you want to be in this life and in this world. What kind of difference do you want to make in this world? Find the joy in cherishing clothes, in customizing them, in repairing them, in sharing them. Build a deep connection with the natural world and know your place in it, as an integral part of it.”

Zero-Waste Design and the Home Sewist

When you sew your own clothing, you control fit, print, silhouette, pattern, and yes, even the amount of waste you produce. Even adapting one or two zero-waste design principles can decrease the scraps generated by sewing.

Tweak Cutting Layouts

A simple way to decrease waste is to cut fabric in a single layer instead of on the fold. Wiggle pattern pieces around, nestle sleeves or princess-seamed bodice pieces into the triangular wedges created by a full skirt. Many zero-waste designs lay sleeves on the cross-grain, and this principle can be also adopted by the home sewist (this provides an overview of grainlines). Yokes or yoke facings can be pieced together, allowing smaller bits of fabric to be used up. Bias strips can also be pieced from small scraps instead of fresh expanses of fabric. Facings and linings can also be cut from the leftover scraps of another project. Finally, by keeping a favorite panties, bra, or camisole pattern on hand as you layout pattern pieces on fabric, you might find that a little wiggling will allow you to eke an extra garment from that length of fabric.

Tweak Patterns

In zero-waste design, shaped seams are sometimes replaced by darts and ease added to a pattern, such that side seams become straight lines. This allows pattern pieces to lie flush against one another, eliminating wasted fabric between pattern pieces. If pattern manipulation intrigues you, try out one or more of these ideas in a simple garment. Zero-waste designers also think creatively about using up the odd pieces of fabric inherent in armscyes, necklines, etc. Facings get extended downward or inward; while a neck facing may no longer mimic the neckline, it’s still functional and produces no scraps. Other uses for these odd bits of fabric include shoulder pad coverings, fabric-covered buttons, fabric embellishments like flowers or circles, bias binding, welt pocket or bound buttonhole strips, and piecing together several lengths to create a fabric belt. Changing seamlines and grainlines will change the way the final garment behaves, but the creative challenge can open up new ways of thinking about shape, ease, volume, print, fabric, and fit.

Ultimately, zero-waste design is about creativity flourishing within restraints. Vionnet used the fewest number of seams and pieces possible, and in doing so introduced the fashion world to new ways for using the bias. Rissanen is likewise stimulated by the creative challenge inherent in zero-waste design. “The uncertainty is exciting once you embrace it.” Perhaps, for some sewists, manipulating cutting layouts and patterns to reduce waste will likewise inspire new ways to view garment construction, elevating their practice to a new level.

Further Reading

- Timo Rissanen and Holly McQuillan recently released Zero Waste Fashion Design, a comprehensive book that includes interviews, cutting tips, a historical overview, and discussions with designers.

-

Make Use includes seven free patterns that you can download and use. - Julian Roberts offers a free e-book about subtraction cutting, the process for creating garments by removing fabric.