"And when he does his little rounds, 'round the boutiques of London Town, eagerly pursuing all the latest fads and trends, 'cause he's a dedicated follower of fashion."

–The Kinks, 1966

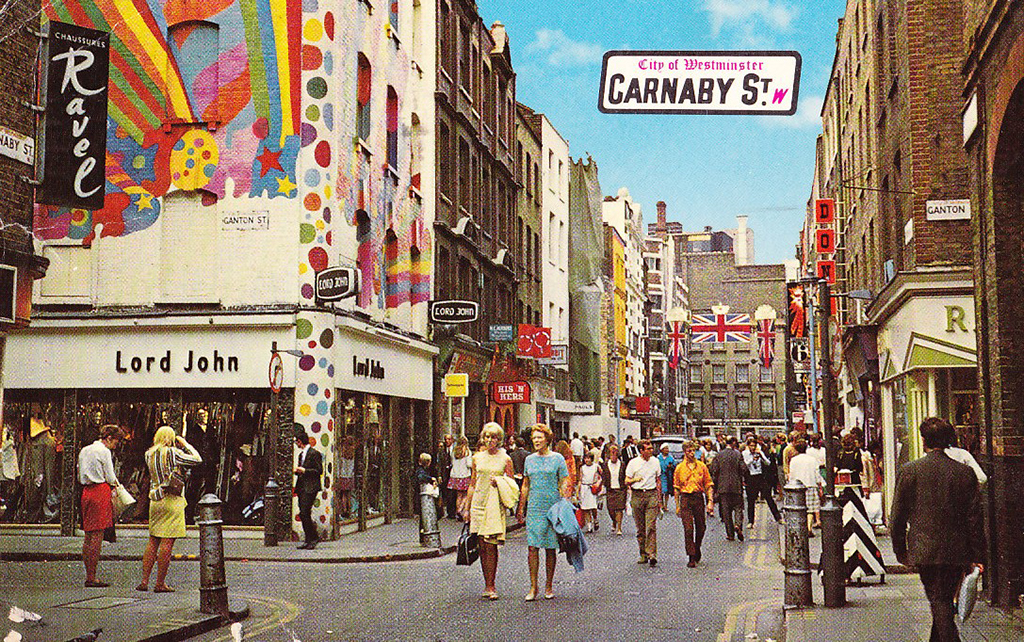

Carnaby Street in the 1960s was a hallowed place—a pinnacle moment where art and music came together in a singular place formerly unknown to the world: the boutique. A synergy would emerge from the revolutionary-minded youth culture and the traditional world of retail who would not only re-design the ideas of a generation but also of commerce. This undistinguished street was the genesis of what we now know as “street style” and introduced innovative, independent designers who still inspire our way of dress today.

A postcard showing Carnaby Street in the mid-1960s.

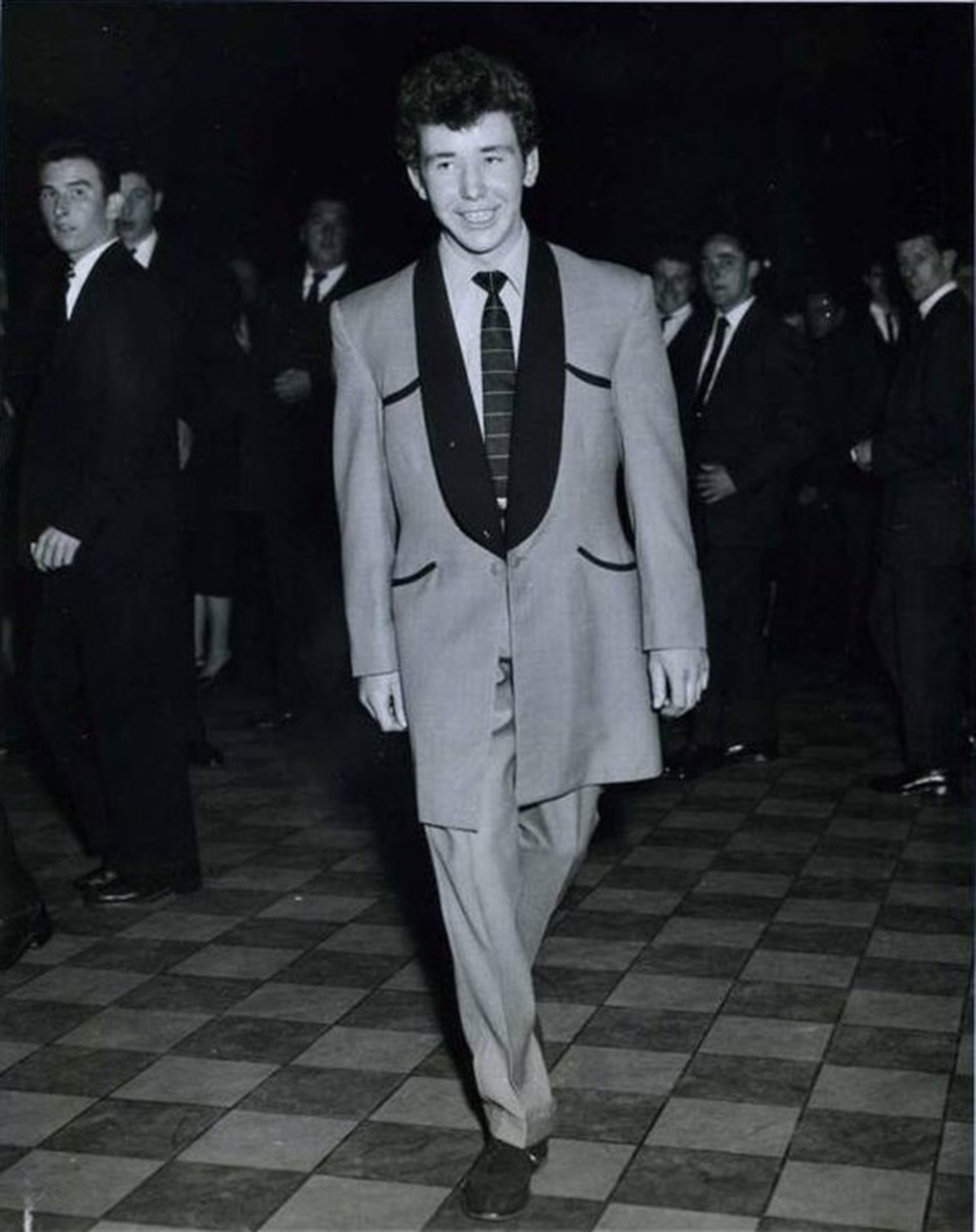

A NeoEdwardian suit from the

late 1940s.

Back to the Beginning

To understand where Carnaby came from, we have to briefly examine the life and uniform of the British man in postWorld War II England: dark, boxy, conservative, with a fair amount of tweed. It was a somber look that reflected the warweary views of a shellshocked nation as they picked up the broken pieces of their cities. The war generation threw themselves into a life of domesticity and tradition, a cocoon after years of turmoil. Safe, solid, drab.

In the early 1950s, as Christian Dior was introducing a new look to women’s fashion, the tailors of London’s Savile Row were doing the same for the British upper class. Snubbing the Labour government’s call for austerity, Savile Row decided to resurrect the fashion of the Edwardian Era, typified by narrow trousers, a lengthened, narrow, fourbutton jacket, and a doublebreasted waistcoat. Originally embraced by an upper class audience, the style soon swept out of Mayfair, a district in London, England, and over the Thames River, where it was commandeered by working-class youth.

A young Teddy Boy wearing a stylish suit featuring black lapels and piping.

The Teds Tear It Up

The emergence of the socalled Teddy Boys in the 1950s (Teddy being short for Edward and Teds being shorter still) saw the neoEdwardian suit transformed into a strange amalgamation, including influences from American Western culture and zoot suits. Bill Haley and the Comets’ “Rock Around The Clock” hit British airwaves in 1955, and the Teddy Boys embraced rock ‘n’ roll with open arms. This established the precedent of a particular style associating itself with a certain type of music.

Today, nearly everybody chooses their clothing as a way to express themselves as individuals and to signal other likeminded individuals of their interests. Before the Teds, teenagers did not have a way to express themselves—no uniform to connect them to a particular tribe. At that time, most teenagers dressed in the same style as their parents. Suddenly, kids had their own interest in style and the money to buy their own clothes. This had the effect of creating a new target market for retailers. At the beginning of the Teddy Boy movement, suits were custom-made or altered, but savvy retailers soon saw that they could manufacture and sell readymade garments directly to this new youth market.

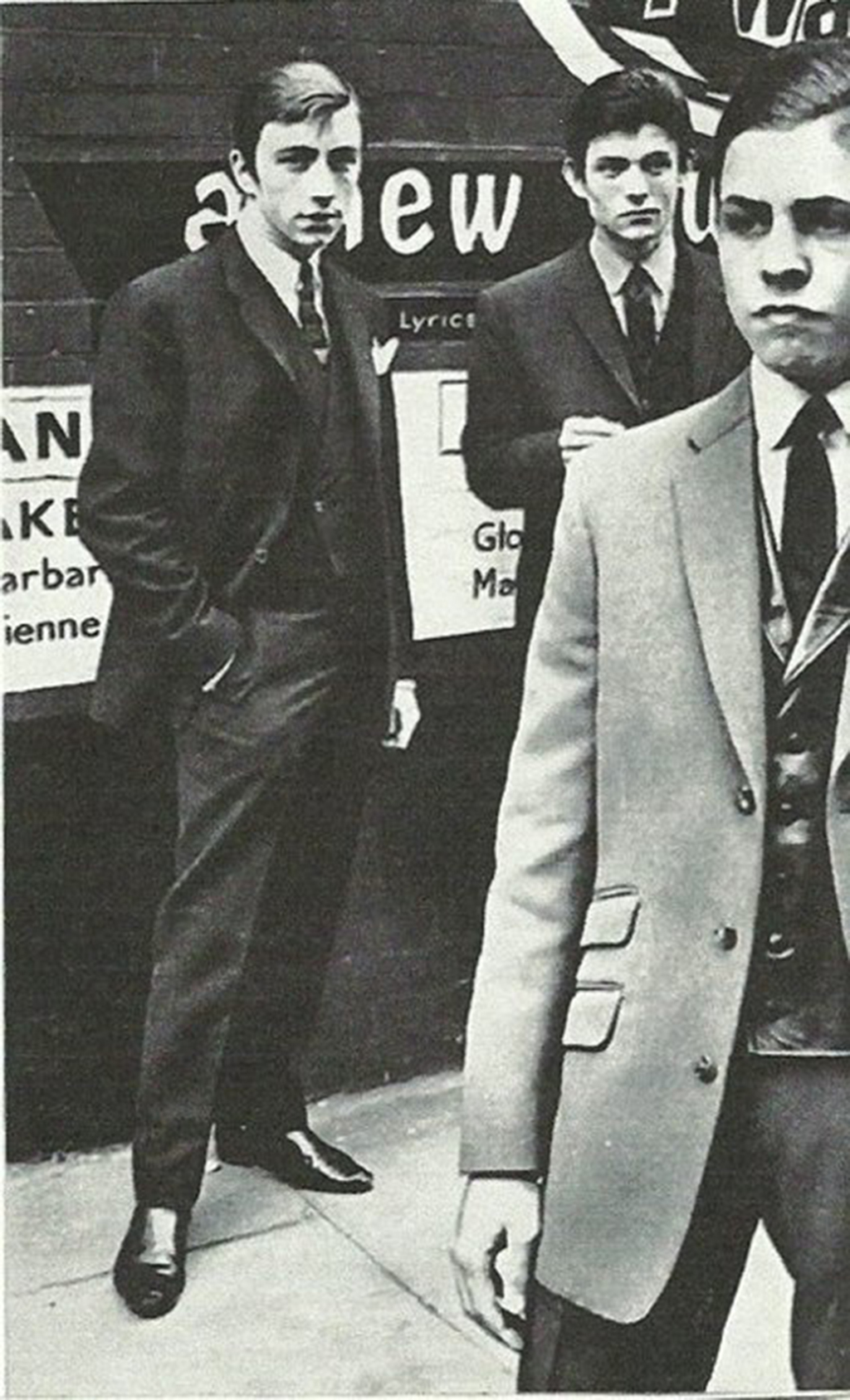

The Mods Take Measure

A different style of teenage rebellion was percolating in the dark jazz clubs of London’s Soho district. During the war, Soho had been a refuge for American serviceman who brought to the tawdry district their favorite music—jazz. After the war, both the soldiers and the jazz stuck around, and in the late 1950s, more London teenagers flocked to hear the music and buy black market Levi jeans from the Americans.

The mods, as these “modernist jazz”-loving teens were called, preferred Ivy League slim suits and dark glasses. Detail oriented and exacting, the Mod was obsessive about every aspect of his look. Whereas the Teddy wore his look as sort of a uniform, the art student mod always endeavored to look different. A cut of jacket, slight lengthening of the collar or tie, and button placement were all worthy of hours of consideration. A welldressed mod would constantly evolve his look. These mods and their preoccupation with dress were the launching pad for Carnaby Street.

Young mods in the early 1960s. On the right of the image is a very young Marc Bolan, who would later front glam rock group T. Rex.

Commerce Comes to Carnaby

Bill Green opened Vince Man’s Shop just east of Soho in 1954. This shop, considered the first true boutique in London, sold modern clothes—tight fitting, brightly colored, and awash in exotic fabrics like velvets and silk. Originally, its camp style sold to a mainly gay clientele. But soon, its look was picked up by the mods and started to filter into the mainstream.

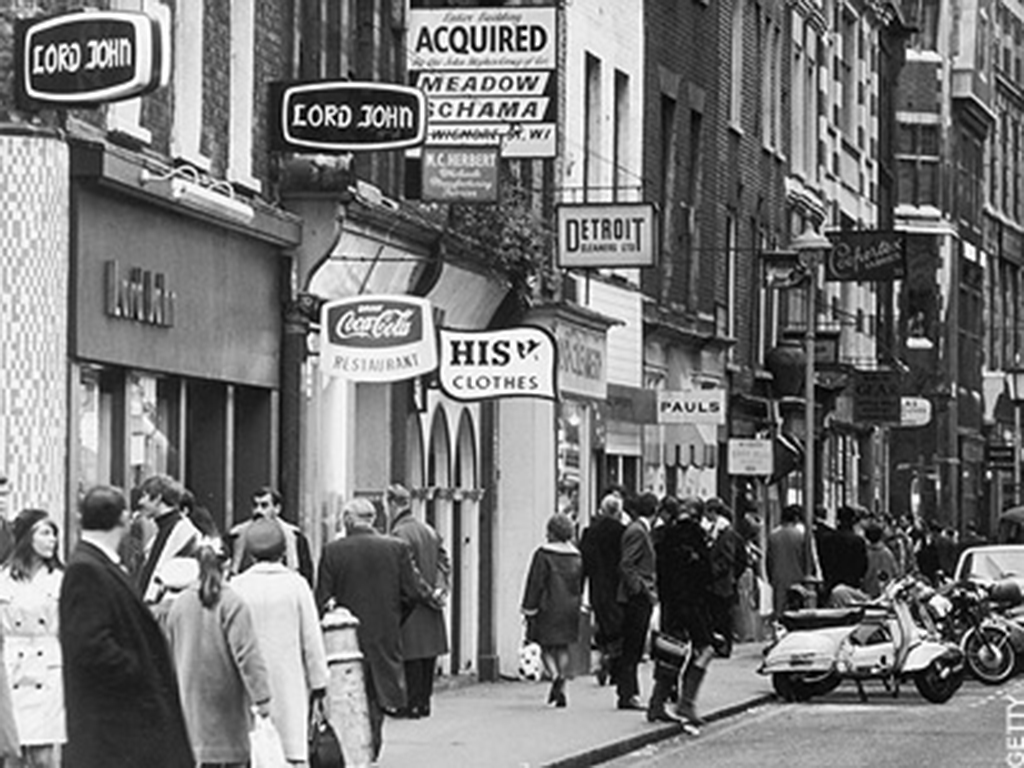

It was John Stephen, a sales clerk at Vince, who brought this new look to Carnaby Street. In 1957, Stephen, who would eventually be known as the “King of Carnaby Street,” opened HIS Clothes in what was then a sea of dowdy shops and warehouses. Although not fashionable, at the time Carnaby was cheap and sat in a wellplaced location. One entrance to the street landed just behind Liberty of London and close to the retail worlds of Regent and Oxford Streets. It also fell just east of Soho, where the mod revolution was just beginning.

A view of Carnaby Street showing John Stephen’s HIS Clothes.

The key to Stephen’s success was his age. He was the same age as the majority of his clients and understood not only that the new youth market had money to spend, but that it also wanted to revolutionize its style. Stephen designed and manufactured his clothing in the back of his shop, enticing customers with his everrevolving front windows and blasting a soundtrack of the most current music. He understood that by observing the mods and their street style, he would be able to design and market to their whims. His designs were offered at low prices, enabling any working teen to afford a weekly trip to HIS Clothes. Stephen would eventually open a total of fourteen stores on Carnaby Street, including legendary names such as Male W1, Domino, and His ‘n’ Hers. His success quickly drew other retailers to the area and boutiques such as Lord John, Gear, and Mates joined the scene.

The front window of John Stephen’s

store Male W1.

Warren Gold started Lord John with a booth in the Petticoat Lane street market and had such success selling suede jackets and coats that he was able to move to a storefront in Carnaby. His focus on street style made sure that he was able to keep pace with the most current mod look (not an easy task as it changed on a weekly basis). At this point, mod style was in full swing, and an army of young men spent their days and money refining their look. The slim Italian suits were layered with army parka jackets and desert boots. For the sporty mod, Fred Perry tennis shirts and Pop Art graphic tops made bold statements.

Keith Moon and John Entwistle of The Who sport Pop Art mod fashion.

Welcome to Swinging London!

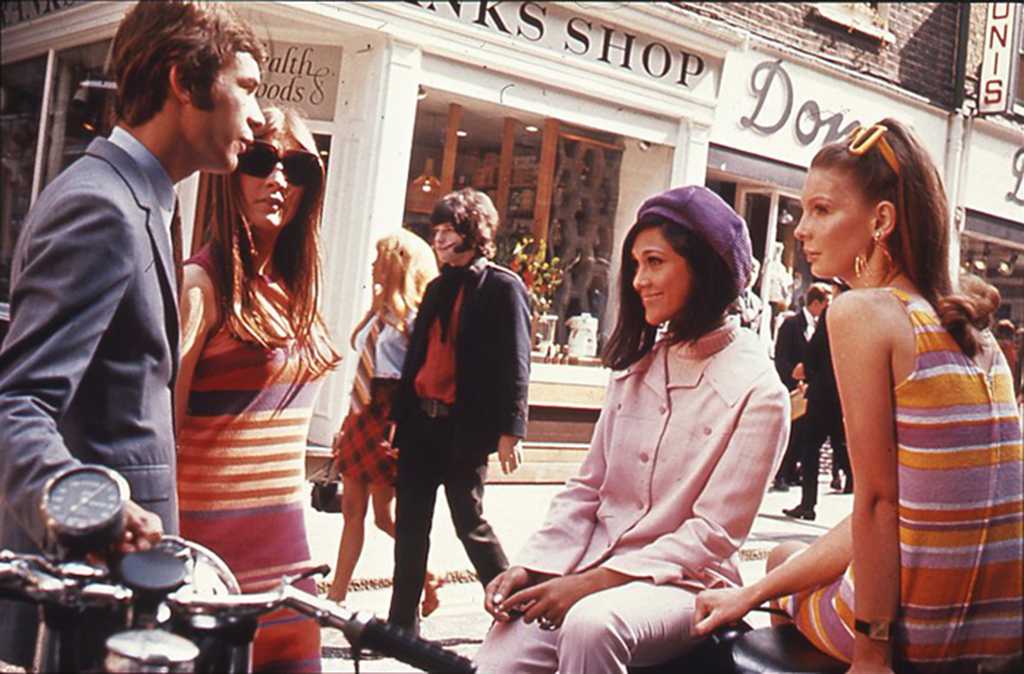

By 1964, Carnaby Street really started to swing as the likes of the Rolling Stones, The Who, The Kinks, and The Beatles made it their premiere shopping destination. This is where the synergy between music, art, and fashion collided. Many musicians, including John Lennon, Pete Townshend, and Keith Richards attended art college and were incredibly visually creative as well as musically. There was a cyclical influence between them and the burgeoning fashion designers. As the music became more popular, the audience wanted to emulate the bands and the only place to find that kind of clothing was Carnaby Street.

Not since the era of Beau Brummel, who once claimed it took him five hours to dress, had such an intense focus on “a la mode” overtaken the male population. Brummel was a socialite in England’s Regency Period (1811–1820) who introduced and established the modern man’s suit as popular fashion. Brummel exerted an influence on the upper class of England’s interest in style, creating the group known as the “dandies.” This term would be dusted off for use again for the flamboyant “Carnabetian Army” and their pageantry of dress. The Kinks’ 1966 song “Dedicated Follower of Fashion” immortalized these young peacocks with the lines:

There’s one thing that he loves and that is flattery. One week he's in polka dots, the next week he is in stripes, 'cause he's a dedicated follower of fashion

Peacocks strutting on Carnaby, by H. Grobe own work via Wikimedia Commons](https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)

Fashion, as always, evolved. A slightly flared trouser morphed into bell-bottoms. Brighter colors and busy prints gave way to rainbows and paisley. By 1966, Carnaby Street was in full psychedelic mode. This new romantic way of dressing was heavily influenced by different eras of vintage fashion. The boutique I Was Lord Kitchener’s Valet was an instant success selling nineteenth century military jackets, fur coats, and Victorian paraphernalia. London’s old guard was incensed by the resale of respectable military garments to brash young teenagers, but their opinions hadn’t a chance against Mick Jagger who wore a Valettunic on music’s hottest show, “Ready, Steady, Go.” The next morning, one-hundred people were lined up at the door, and the shop was sold out by midday.

A young man tries on the military style at I Was Lord Kitchener’s Valet, photo by Paul Townsend from Bristol, UK via Wikimedia Commons.

Cool Kids in King’s Road

Although Carnaby Street was the nucleus of the London scene in 1966, it had become overrun with tourists due to LIFE magazine’s April article glorifying “Swinging London.” While the street still thrived, independent designers were moving to other parts of London. A quick jaunt over to King’s Road was essential for trips to Quorum, Biba, Bazaar, and Granny Takes a Trip. Granny was another boutique that had originated selling antique clothing found at street markets. When the shop sold out on their first Saturday in business, owners Sheila Cohen, Nigel Waymouth, and tailor John Pearse scrambled to design and manufacture their own stock. Granny created a romantic, antique look, incorporating Victorian lace, William Morris prints, and Art Nouveau details.

In 2012 the British government issued a

Royal Mail stamp celebrating fashion from

Granny Takes A Trip.

Mayfair was another stop for the welldressed London man. Michael Fish, a designer for traditional shirtmaker Turnbull & Asser, opened his boutique Mr. Fish in 1966. A reaction against the conservative suit, Mr. Fish offered bespoke menswear in outrageous, colorful designs. He changed the cut of men’s dress shirts, widening the collar and offering it with a ruffled front in silks and satins and also created the wide “kipper” tie. With its paisleypatterned ties and velvet double-breasted jackets, Mr. Fish was the boutique for the gentleman who had money to spend on beautifully tailored jackets in expensive fabrics.

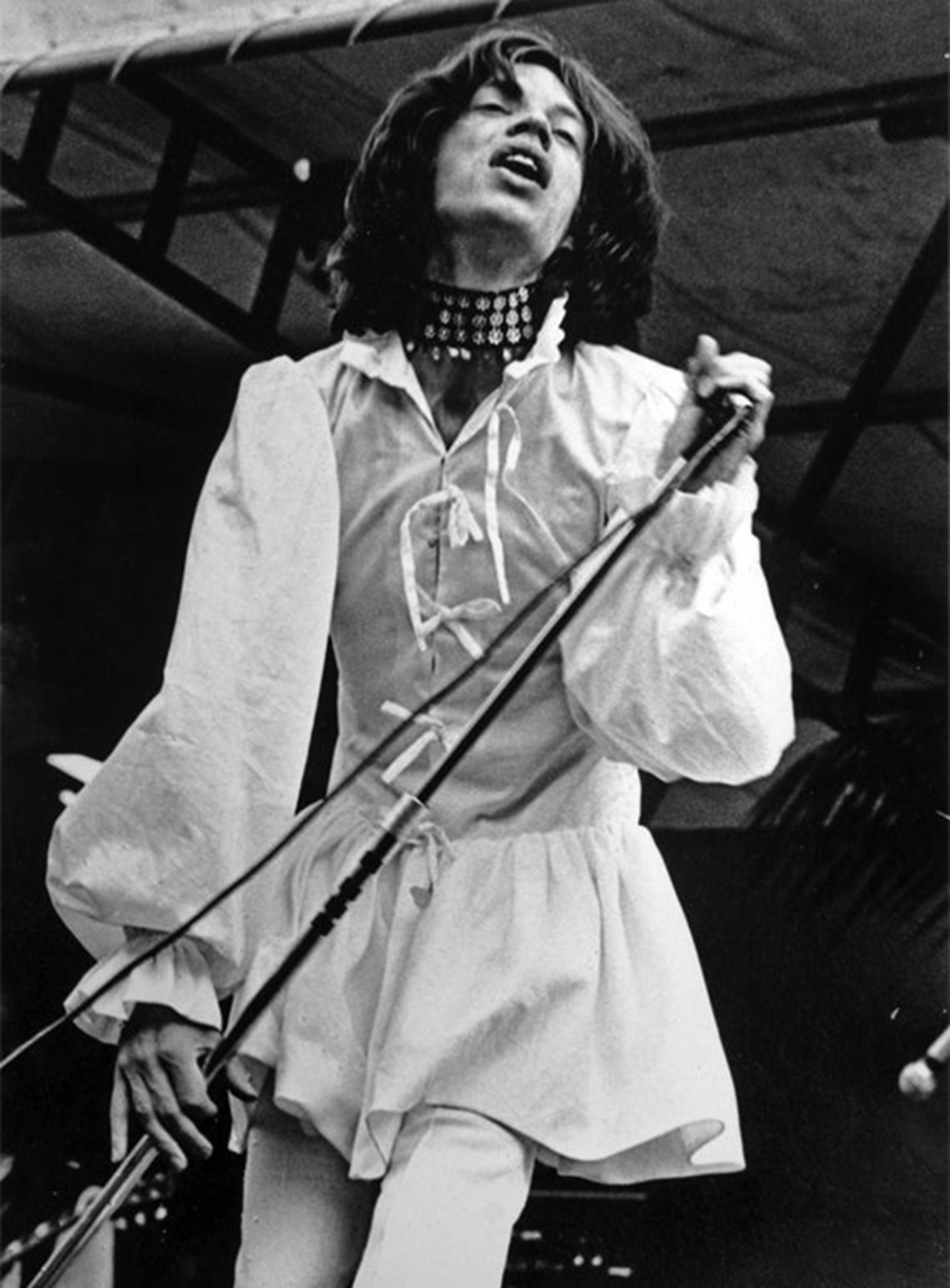

Mick Jagger wearing his Mr. Fish dress at the

Rolling Stones 1969 Hyde Park concert.

Mr. Fish was also one of the first designers to step into androgynous territory, when he started designing dresses for men. Mick Jagger famously wore a Mr. Fish white men’s frock for the Rolling Stones’ 1969 Hyde Park show. The ensemble featured bows, bishop’s sleeves, and a ruffled collar worn over slimfitting white trousers. Jagger accessorized with a black leather studded collar. The press touted it the “dress,” but it was really more of a smock, which had been inspired by a traditional skirtlike costume worn by the Greek presidential guard. For a proper man’s dress, look no further than Mr. Fish’s maxi dress that David Bowie wore on the cover of his album, “The Man Who Sold The World.”

Tommy Nutter’s shop, Nutters of Savile Row, was another bespoke menswear option for rock’s elite. Nutter had trained with traditional Savile Row tailors for seven years before opening his own boutique. His contemporary tailoring, which featured wide shoulders, large lapels, and bold fabrics were combined with traditional menswear techniques. His exquisitely cut suits were not only popular with men (he dressed three out of four Beatles on the cover of “Abbey Road”) but also with women. Both Mick and Bianca Jagger wore Tommy Nutter suits to their 1971 wedding.

Mod Menswear Made Modern

Midcentury menswear designs are often referenced as inspiration by designers today. Tom Ford, who brought back slimfitting velvet suits during his tenure with Gucci in the 1990s, has cited Nutter as inspiration; as has John Galliano, who worked with him briefly during his time studying at Central St. Martins.

The influence of the menswear from the 1960s is felt not only with elite designers like Ford and Galliano, but also within readyto-wear shops such as J. Crew, H&M, and Topman. Here you will still find the slimcut suits reminiscent of those worn by the mods. Ben Sherman, a popular Carnaby designer in the 1960s who outfitted mods with sharpfitted shirts, is now an international brand still going strong.

Carnaby Street today with original mod

store Ben Sherman, photo by

Philafrenzy via Wikimedia Commons.

With the advent of street style blogs like The Sartorialist, Men In This Town, and Gentlemen’s Brim a dandyinspired interest in fashion has once again hit the mainstream. With independent designers opening digital boutiques, fashion styles that would once have been limited to a geographic area can instantly reach a worldwide audience.

The original street style: Mod girls and guys hanging on Carnaby Street, photo by The National Archives UK (no restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons).

The lasting legacy of Carnaby Street is not seen in the elegance of a man’s suit or his enthusiasm for fashion. It is the idea that fashion can be used as an outward indicator of a belief system and can signal that the wearer belongs to a culture or movement. The mods wore sharp suits, the punks leather jackets, and now hipsters display beards and glasses. The alliance of fashion and ideas continues now and into the future.

Bring the sounds of Swinging London to your home with my recommended Carnaby Street playlist!

My Generation, The Who

The House Of The Rising Sun, The Animals

To Sir With Love, Lulu

Paint It Black, The Rolling Stones

Dedicated Follower of Fashion, The Kinks

Strange Brew, Cream

As Tears Go By, Marianne Faithfull

Itchycoo Park, Small Faces

Je t’aime... moi non plus, Jane Birkin & Serge Gainsbourg

Norwegian Wood, The Beatles

For Your Love, The Yardbirds

She’s Not There, The Zombies