Ever since Kate Middleton’s lace wedding dress made a splash in magazines across the world, lace has dotted popular looks on runways and in DIY sewing circles. Most people don’t realize that the lace in her dress was made by an English company, or that the last two centuries have seen the rise and fall of English lace production. The very company that inspired this lace revival, an English company situated in the heart of the former epicenter of lace production, embodies this shifting history.

The Origins of English Lace

Traditionally, Nottingham and its surrounding cities in the East Midlands region of England were the center of the world’s lace industry. The industry started with handmade lace, but boomed with the invention of mechanized lace production in the late 1700s. The 1901 census for Nottingham lists over 20,000 people, mostly women, as employees of the lace industry. At the height of production, roughly 200 factories produced lace in the region. Higher-paying jobs such as setting up and operating the machinery were reserved for men. Women were often found in the steps of the process required to finish the lace, including bleaching, repairing, and embroidering.

The Nottingham lace trade began to decline in the twentieth century. The first major blow to the industry came during the First World War, when trade disruptions affected the ability to fulfill orders. In subsequent decades, most companies found themselves unable to compete with cheaper imports, and many went out of business. In the 1950s, there were still over 100 lace factories in the Nottingham area. Half a century later, just one remains.

Cluny Lace

The last remaining lace factory sits on an unassuming residential street in Ilkeston, England. Owned and operated by the Mason family, the company first produced lace made with hand-operated machinery. This was in the 1760s, at the start of the Industrial Revolution. Since then, nine generations of the Mason family have run the company, originally known as Mason’s and now known as Cluny Lace.

The Cluny Lace factory building.

Cluny Lace has been based in their current factory building since the 1880s, when it was purposefully built to accommodate specialized lace machinery. At that time, Cluny Lace was one of multiple occupants in the factory, then surrounded by neighboring lace factories, but they are now the sole tenants of the building and the surrounding area has become a largely residential area.

The company, and historically the local industry, always specialized in producing cluny lace. Cluny lace is a term used to describe bobbin lace with a geometric design. The most traditional cluny lace designs, which the company still produces and which remain best sellers to this day, are usually composed of multiple squares. These designs are based on even earlier handmade lace patterns where, due to the time required to produce lace by hand, each square would have been created separately, often by different women, and then pieced together at the very end.

Cluny Lace uses traditional production practices to create beautifully intricate designs.

The company is unique for both its longevity and also for its production process. Their lace is entirely produced on traditional Leavers lace machines. At the height of the lace industry, as large quantities of lace were being produced, local tinkerers began devising new and better ways to produce lace. The Leavers machines were a local invention and many Leavers lace machines were produced by Jardine’s of Nottingham, who in the early 1900s produced as many as 300 machines per year. A glimpse into the factory floor reveals machines with “Nottingham” proudly stamped on the foot plate of these locally produced machines.

A Peek into the Traditional Production Process

Leavers lace machines.

The Leavers lace machines are composed of two parts: the Leavers machine produces the lace and a Jacquard machine controls the pattern. Each machine holds three to four thousand threaded bobbins. Larger and flatter than sewing machine bobbins, these bobbins swing in a pendulum-like motion, always taking the same path as they twist around the warp thread. The warp thread is fed into the Leavers machine through 60 to 160 steel bars, each 4/1000 of an inch thick, which connect the Leavers and Jacquard machines.

The Leavers lace machines use thousands of bobbins to create lace.

The lace pattern is determined by a series of punched Jacquard pattern cards that control the order in which the warp thread passes through the steel bars. The resulting lace is a twisted lace. This process closely replicates the process of making lace by hand, and Cluny Lace is able to create intricate designs that are impossible to make on the contemporary Raschel machines, which are used to produce 99% of lace globally. These modern machines instead create knitted lace, which can be produced much more quickly than twisted lace but lacks its beautiful intricacy. Until 15 years ago, Cluny Lace also had a Raschel machine plant but was unable to compete on price, and thus decided to sell the modern machinery and focus entirely on the Leavers lace machines, many of which have been with the company for generations.

Jacquard pattern cards are used to create intricate lace designs.

The Leavers lace machines are enormous. They weigh around 20 tons when fully laden, and each machine occupies 500 square feet. Cluny’s 16 machines are powered by electricity and any original parts that break are repaired with plastic parts, but otherwise these machines differ little from the original steam-powered machines. The lace itself comes off the machines in standard widths that are determined by the size of the machine, and typically in lengths of 20 to 25 meters. Once off the machines, the lace is checked for damage and repaired if needed. Then it is shipped to Calais, host to the sole remaining lace dye works plant in Western Europe, to be washed and dyed. Finally, the lace is sold by the bolt or cut into strips to be used as trim.

Shifting Trade Winds

Historically, the majority of lace produced in the region would have been intended for household textiles, such as table clothes and handkerchiefs. Twenty years ago, Cluny Lace exported the majority of its lace to Spain and Italy for lingerie production. In the last 10 years this market has dipped, and their largest market is now garment production, with customers that include Burberry, Jigsaw, Vivienne Westwood, Paul Smith, Dolce and Gabbana, Etro, and Christian Dior.

To distinguish themselves from cheaper competitors and meet the requirements of the couture market, Cluny Lace only produces lace using cotton and nylon, with 90-95% cotton content. The company has an archive of thousands of designs, and roughly 250 designs are in production at any given time. These are often selected based on the designer’s experience of which designs sells well, and many designs have been in production for generations.

A Dying Art

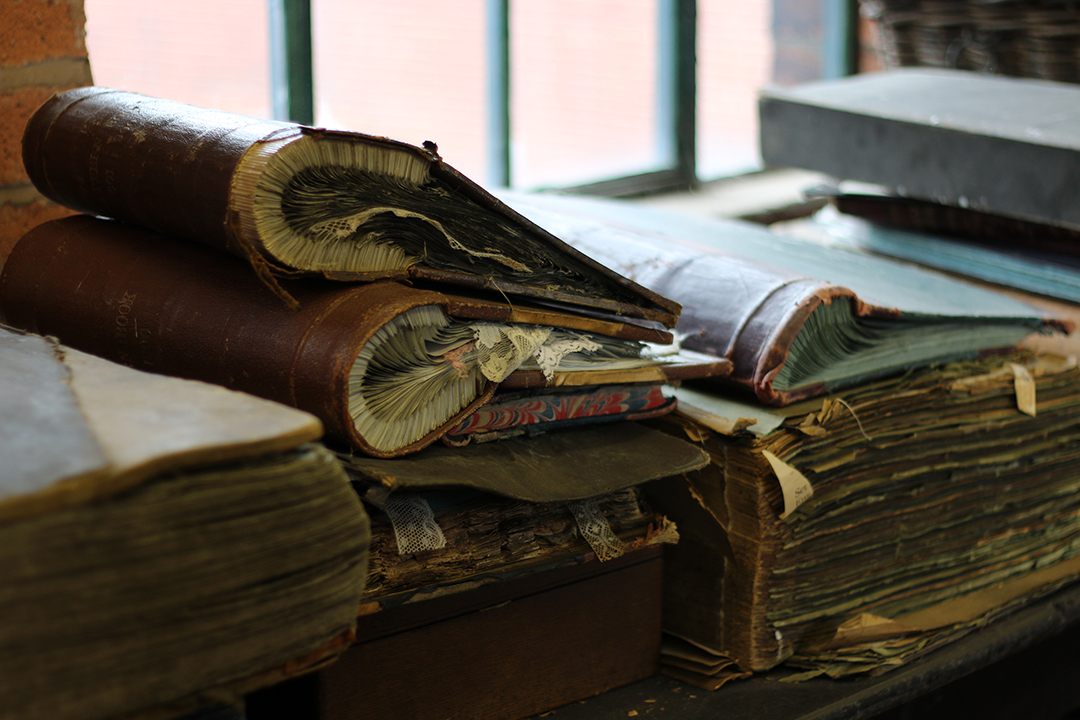

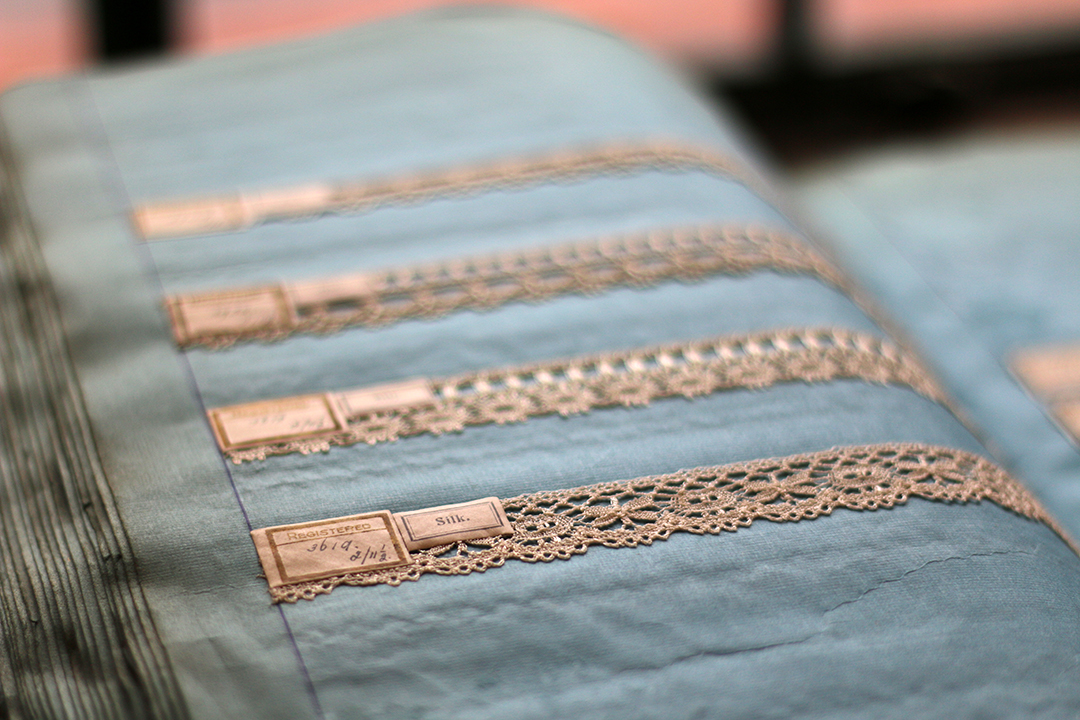

Cluny Lace’s archive of lace patterns was designed in-house throughout the history of the company, and they were also purchased from local companies that closed down. One room houses thousands of machine patterns. The room also contains beautiful sample books, containing historic swatches of lace in a multitude of sizes, designs, colours, and materials, including beautiful silk lace. As the last remaining factory in the region, they are a valuable repository of the region’s lace-making legacy.

Lace sample book. Multiple iterations of a single motif are often clustered on the same page.

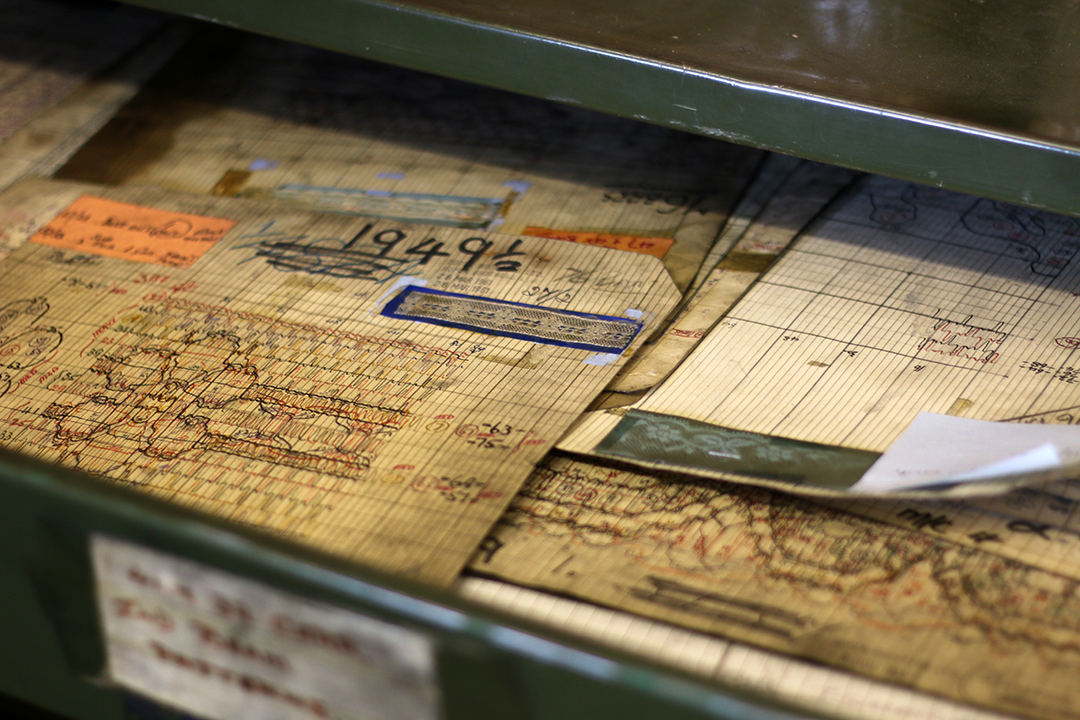

To the untrained eye, the lace patterns look like multi-coloured doodles on large sheets of grid paper. Before they can be used by the machines they need to be converted into binary code, which is then used to determine the order in which holes are punched into a series of Jacquard cards. Cluny Lace employs the UK's last Jacquard card puncher, who is able to take or modify the existing pattern designs and create the elaborate system of holes in the Jacquard cards that determine the pattern the machines weave. The skill set required to design new lace patterns for the Leavers lace machines was never abundant and has already been lost.

Jacquard machine lace pattern designs.

This isn’t the only skill that may soon be lost; considerable training is required for many jobs in the lace industry. To become a twisthand, or the person responsible for setting up and operating the lace machines, traditionally required several years of apprenticeship. With no industry to support job creation, there is a real danger these skills will be lost altogether.

Despite the recent uptick of interest in lace, the era of English-produced lace may be drawing to a close. The industry faces multiple headwinds, including overseas competition, a dwindling labor pool, and diminishing appreciation of its beautiful laces. Fashion is an industry of reinvention; wait 20 years and looks come back into vogue, as the passage of time allows “frumpy” to become “retro” or “updated.” Perhaps Cluny Lace will weather the storm. If not, their valuable production processes, thousands of intricate designs, and the legacy of English lace, will be lost forever.