“Embroidery is to haute couture

what fireworks are to Bastille Day.”

-Francois Lesage

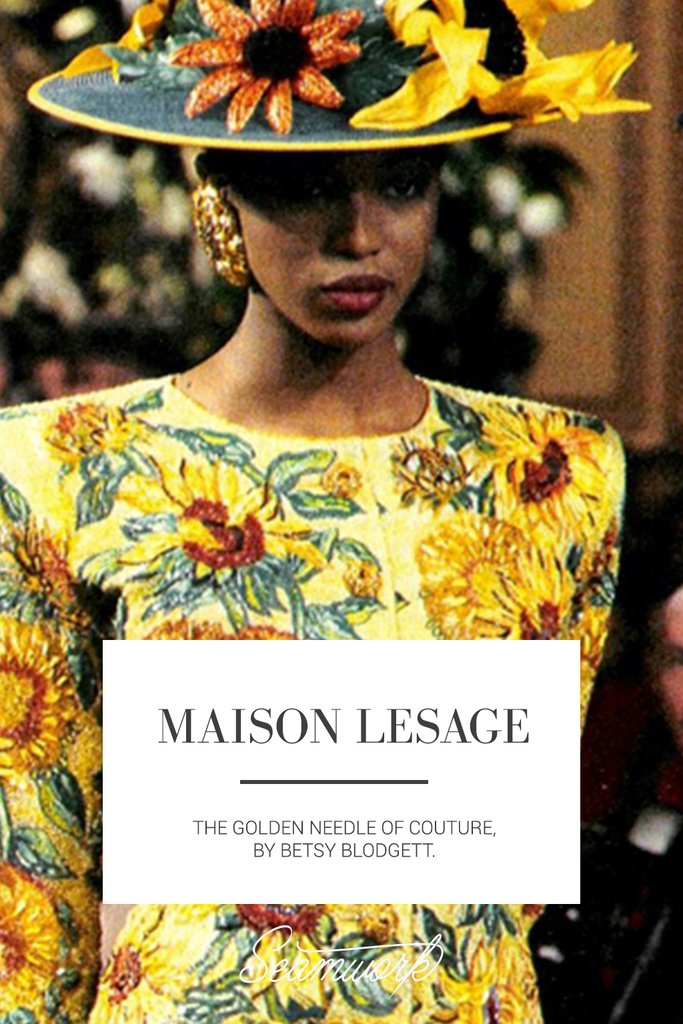

Haute couture is the dream around which the fashion world revolves. One embroidery house, Maison Lesage, has been stitching up lush, richly detailed fabric pieces for couturiers like Balenciaga, Dior, and Schiaparelli since the inception of haute couture in the mid-1800s. When you see Chanel send a richly beaded, sequined, or feathered garment down the runway, you are seeing a piece of Maison Lesage art.

While Maison Lesage represents all that is luxurious in haute couture, it also represents the struggle of the luxury fashion industry. Far from the runways of fashion week, along narrow streets, behind unassuming doors, are the ateliers—the workshops of Paris. These ateliers, which once employed thousands of seamstresses, have become an endangered species. As these bastions of creativity die off, those that remain must struggle to find their place in contemporary fashion. Maison Lesage, Paris’ oldest embroidery atelier, is a living museum of luxury. Here, old world craftsmanship is meeting fashion’s future through innovative design and a determination to keep a centuries-old technique relevant for today’s designers.

It is difficult to speak of Lesage without the risk of uttering the commonplaces of perfection, because with him, we are on the edge of ‘the self-evidence of the masterpieces.’

-Christian Lacroix

The First Stitch

Imperial Russian Court Dress by Charles Frederick Worth, circa 1888. By the Indianapolis Museum of Art via Wikimedia Commons.

Schiaparelli evening dress embroidered with key motif,

1939. By Mabalu (photograph), Elsa Schiaparelli (dress);

via Wikimedia Commons.

The roots of the house of Lesage go as far back as the Second Empire in France. Known as Michonet when it was founded in 1858, its embroidery designs were highly sought after among Paris’ fashion elite, including the father of haute couture, Charles Frederick Worth, as well as the court of Napoleon III. In 1924 Albert and Marie-Louise Lesage purchased the company and created avant-garde embroidery designs that attracted the likes of designers such as Madeleine Vionnet and Elsa Schiaparelli.

The Lesages both had backgrounds in women's fashion. Albert, originally from Paris, had been the director of women’s clothing at Marshall Field’s in Chicago, Illinois, before he moved home to work with Michonet, while Marie-Louise was the assistant-in-charge of embroidery at Vionnet. Their combined experience gave them a unique perspective on the design needs of the couturiers of Paris. They started creating their own in-house designs using the process of tambour embroidery, also called Luneville embroidery.

Tambour Embroidery

Although man has enhanced his clothing with embroidery from antiquity (examples of embroidered garments have been found in China dating back to the fifth century BC), the technique was first introduced to Europe via trade routes from Persia in the twelfth century. During the Renaissance, embroidery workshops multiplied in France to keep up with the demand for gold thread and silk embroidery. Appreciation of this artisanal work continued into the eighteenth century, when embroidered imports from the West Indies were banned in order to promote French artisans.

Late nineteenth century handkerchief featuring cotton tambour embroidery on cotton net. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, via Wikimedia Commons.

The roots of tambour embroidery reach as far back as eighteenth century Persia. By 1770, the technique had found its way to France. Tambour uses a hooked needle—a small variation of a crochet hook—to create a chain stitch. According to Art of the Embroiderer, written by Charles Germain de Sainte-Aubin in 1770, this method was “just as accurate and six times more expeditious” than the classic chain stitch method.

Tambour embroidery needle, beads, and the wrong side of the vintage textile.

The technique of tambour looks simple, but it is actually a highly sophisticated process. Robert Haven, a renowned tambour instructor in the US, has broken the process down into 10 steps, which must be synchronized in the seconds between the moment when the hook is plunged through the fabric and when it is brought up again. Unlike traditional embroidery, tambour is worked on the wrong side of the fabric. The only thing the stitcher sees is the back of the design. The actual stitching and bead application is worked with the left hand under the fabric and frame.

Right side of a vintage textile featuring tambour embroidery work.

The seamstresses in the ateliers, the petits mains (little hands) who work the intricate embroidery designs have trained for years to reach a couture level of craftsmanship. This kind of expertise is essential for the fast-paced world of couture, where the ateliers will often get their orders from the designers just one month before from the shows are scheduled to begin.

New Markets and Collaborators

When the lost generation landed in France in the 1920s, they brought with them a penchant for excess. The fashion designers of the day, such as Poiret, Chanel, and Vionnet, responded to this exuberant, artistic atmosphere with garments that featured intricately embroidered and beaded designs.

Maison Lesage met this demand for luxury embroidery with aplomb. They used the efficient tambour method of embroidery to apply the beads and sequins designs that were being demanded from the designers. Albert and Marie-Louise also invented new methods of embroidery, like the technique of Vermicelli style beading that they created for Vionnet.

Although the 1920s were boom years for embroidery, the advent of the First World War had brought Lesage to the brink of collapse. Thus Maison Lesage’s situation was tenuous until the late 1930s, when Albert entered into a close design relationship with Elsa Schiaparelli and the company was again on safe ground. Lesage and Schiaparelli collaborated on many of her seminal works, including her Cocteau line art designs and her famed Zodiac Collection.

Schiaparelli black velvet cape embroidered in gold

sequins from the 1938 Zodiac Collection.

Unprecedented Relationships with Designers

Francois Lesage, Albert and Marie-Louise’s son, took over the family business after his father died in 1949. Francois had grown up in the atelier, born “into a pile of beads and sequins,” as he often said, where he kept a watchful eye on the techniques and designs that his parents created. In 1948, at the age of 19, he had emigrated to Hollywood and opened his own studio, Lesage Sunset Boulevard, which he closed upon his return to Paris. Here he worked with costume designers Adrian and Edith Head as well as movie stars such as Marlene Dietrich, who requested embroidered gowns that “transformed her body into a jewel.”

On his return to Paris he continued his family’s work, designing new embroideries and pushing the boundaries of tambour art—despite the fact that he did not even know how to sew a button onto a garment. Just as his father had worked with Schiaparelli, Francois forged close relationships with designers, learning to interpret their sometimes vague requests.

When Yves St. Laurent demanded, “Francois, make me something that is like a chandelier reflecting off the mirror with the sky of Paris in the background,” Lesage was able to accommodate this request.

Richly embroidered haute couture gown by Christian

LaCroix from his 2002 Autumn/Winter Couture

collection. By Florian Vincent, via Wikimedia Commons.

In later years he became something of a mentor for young designers, including Christian LaCroix, who referred to Francois as his “couture godfather.” Today, Maison Lesage continues its cultivation of young designers, often providing them embroidery free of charge.

“Our job is to give intellectual and creative food to the couturier.”

-Hubert Barrere, Artistic Director at Maison Lesage

A finished piece of Maison Lesage embroidery is the product of a partnership between the designer and Lesage. The designer, be it Balenciaga, Dior, or Valentino, starts with a theme, which could be anything from a book, an artist, or even just a word. Lesage takes that theme and responds with up to 30 sample designs, of which the designer chooses but a few.

Each sample design is stored in the Lesage archives, which today holds over 70,000 exquisite embroidered samples. Each design take hundreds of hours of handwork—in fact, Francois Lesage once estimated that the entire Lesage archive represents up to nine million hours of work.

Yves St. Laurent Irises jacket with Van Gogh’s Irises painting.

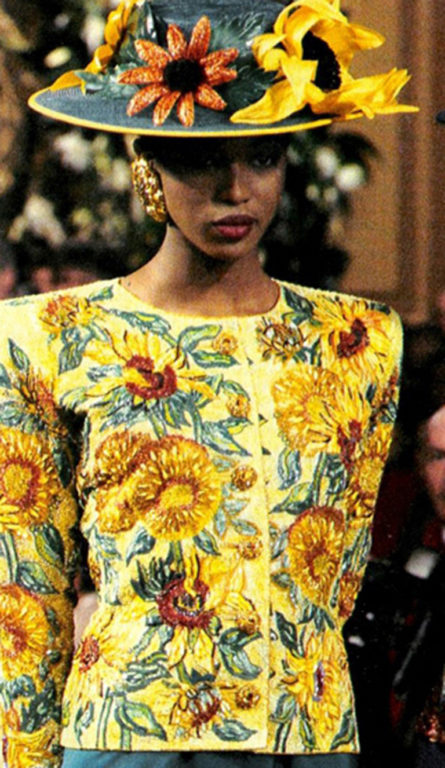

In 1988, Francois collaborated with Yves St. Laurent on two jackets that were inspired by Van Gogh paintings. The jacket based on Irises was embroidered entirely by hand and contained 250,000 sequins in 22 different colors, 200,000 individually threaded pearls, and 273 yards of ribbon. It reportedly weighed over 40 pounds, and it took more than 770 hours of handwork to create the embroidery alone. This kind of work does not come cheap—a Lesage-embroidered jacket can run around $60,000 and a dress usually costs at least $100,000.

Yves St. Laurent Van Gogh-inspired Sunflowers jacket.

The Impact of Ready-To-Wear

"A country that loses its craftsmanship is a country that is dying.”

-Francois Lesage

In the early twentieth century, it was de riguer for wealthy women to have their extensive wardrobes made to order. As the century progressed, the burgeoning prices of couture garments made them too expensive for any but the wealthiest to purchase. By the late 1970s, the fashion houses became more reliant on their prêt-à-porter—or ready-to-wear lines—to pay the bills. Today only a few design houses show haute couture lines, which are mainly used as public relations fodder. The runway shows are considered loss leaders that drive demand for the labels’ less expensive lines.

As the haute couture industry became less and less profitable, many of the artisan ateliers of Paris were forced to shut their doors. Today there are fewer than 10 embroidery ateliers left in Paris. Each atelier closure means there are fewer craftsmen learning specialized skills, such as tambour embroidery. In 1992, in an effort to keep his seamstresses on salary and to pass down the art of embroidery to anyone wishing to learn, Francois opened Ecole Lesage, a school of embroidery. The school, which is located in Paris, offers classes for embroiderers of any level, from beginners to those wishing to study to become a master of haute couture embroidery.

When Karl Lagerfeld took over as Chanel’s head designer in 1983, he began a long working relationship with Maison Lesage. In 2002, Lagerfeld’s appreciation for the craftsmanship of Lesage, as well as for other couture ateliers, led Chanel to create a subsidiary company called Paraffection. Dedicated to the preservation of craftsmanship, Paraffection has purchased 12 ateliers d’art, including Maison Lesage.

While Chanel’s investment has created stability for Lesage and its fellow Paraffection brethren, it is not a free pass. Each atelier is expected to act as a stand-alone company, setting itself up for sustainable profits in the future. Chanel does not intend to monopolize the ateliers for their own use; in fact, they encourage them to develop relationships with other designers in order to encourage their long-term profitability.

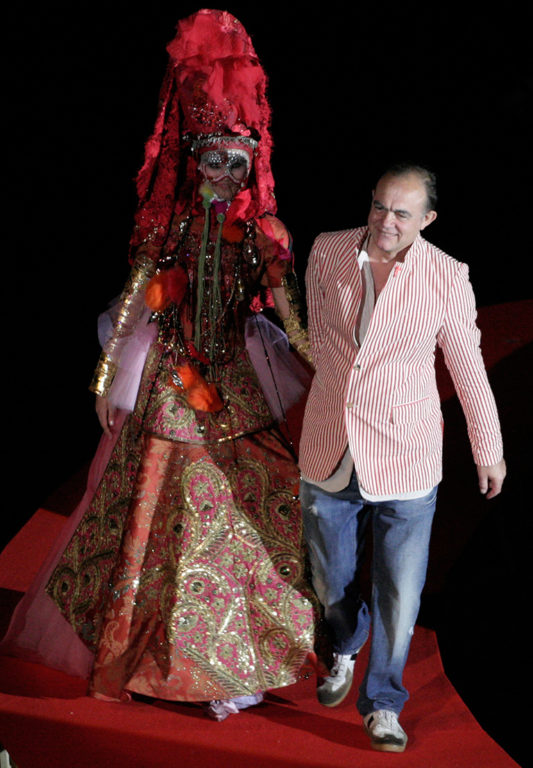

To celebrate the master artisans who work under Paraffection, Chanel created the Metiers d’Art show, which features the work of all the ateliers. This annual show, which is not part of Paris Fashion Week, travels outside of Chanel’s home in Paris, bringing the art of couture masters around the world. Although Chanel has not revealed how much it has invested in preserving these ateliers, it is estimated that they spend $2 million alone on staging the yearly Metiers d’Art show.

The skills of the artisan are a legacy that is passed down from generation to generation. Just as Albert passed along his craft to his son, so did Francois to his son Jean-Francois. However, with the legacy of Maison Lesage safe in the hands of Chanel, Jean-Francois took his heritage with him to India, where he opened his own embroidery atelier Lesage Interieurs, which creates designs for home and fashion. The company also reproduces textiles for historical institutions, including recreating the embroidered wall hangings from Jeanne Lanvin’s bedroom, which is housed in the Musee des Arts Decoratifs in Paris—a fitting project which brings the Lesage legacy full circle, as Lanvin is one of the early designers with whom his father and grandfather worked.

After Francoise Lesage passed away in 2011, Chanel appointed Hubert Barrere to be the artistic director of Maison Lesage. Barrere continues to develop relationships with designers and to promote the artistry of embroidery. “Hand embroidery is something emotional,” says Hubert Barrere. “It isn’t a kind of technical exhibitionism, and its value doesn’t come simply from the hours and hours of meticulous work involved. Above all else, it’s something that comes from the soul, it makes you feel something, without quite knowing why.”

1997 dress by Jean-Paul Gaultier featuring beaded leopard. By W.carter, via Wikimedia Commons.

Under the protection of industry giant Chanel, Maison Lesage has been able to weather the economic downturns that have closed the doors of their contemporaries. But even putting global economics aside, the cyclical nature of fashion can lead to boom and bust time for atelier artisans. The excess of ‘80s fashion, when designers like LaCroix and Valentino kept embroiderers busy, led to the minimalism of the ‘90s, when business plummeted. Chanel’s appreciation for the artistry of Maison Lesage will continue the creative adventure of the house and keep the age-old art of tambour embroidery alive for the next generation of designers.

“I never forget that I am only an embroiderer, craftsman, and my imagination should be framed in simple matter of fact materials—silk, sequins, stones. But they give birth to a firebird dream that I just want to catch on the tail. But the dream cannot be caught—it is always in front, making our life more beautiful …”

-François Lesage.