Of Balenciaga, Coco Chanel enthused, “Only he is capable of cutting material, assembling a creation, and sewing it by hand. The others are simply fashion designers.” In doing so, she flipped the saying—a jack of all trades and a master of none—on its head. As the master of all, Cristóbal Balenciaga was renowned for his ability to redefine silhouettes and construction methods. His most famous creation, the cocoon, was the cut that lay at the heart of Cristobal Balenciaga’s idiosyncratic contribution to the history of fashion. Still, he shattered expectations with his empire waistlines and “baby doll” silhouettes. He introduced the sack dress in 1957 and sent shock waves reverberating throughout the fashion world because, by eliminating the waist, it completely opposed the defining look of the season.

With these futuristic silhouettes and renowned construction techniques, Balenciaga is remembered as a pioneer of construction techniques still referenced today by famous fashion houses during design development.

I will explore Balenciaga’s history, take a closer look at his techniques, and share a pattern hack inspired by his designs.

Balenciaga’s Futuristic Silhouettes

Born in Getaria, Northern Spain, in 1895, Balenciaga was introduced to fashion by his seamstress mother. At the early age of twelve, he began an apprenticeship in San Sebastian at a tailor’s and ten years later, went on to establish his first fashion house. It was called Eisa—a shortened version of his mother’s maiden name.

Balenciaga moved to Paris in 1937 but not before opening fashion houses in Madrid and Barcelona. His thorough early training meant that he overshadowed other couturiers and quickly built an international clientele. He was one of the few foreign couturiers to remain in wartime Paris.

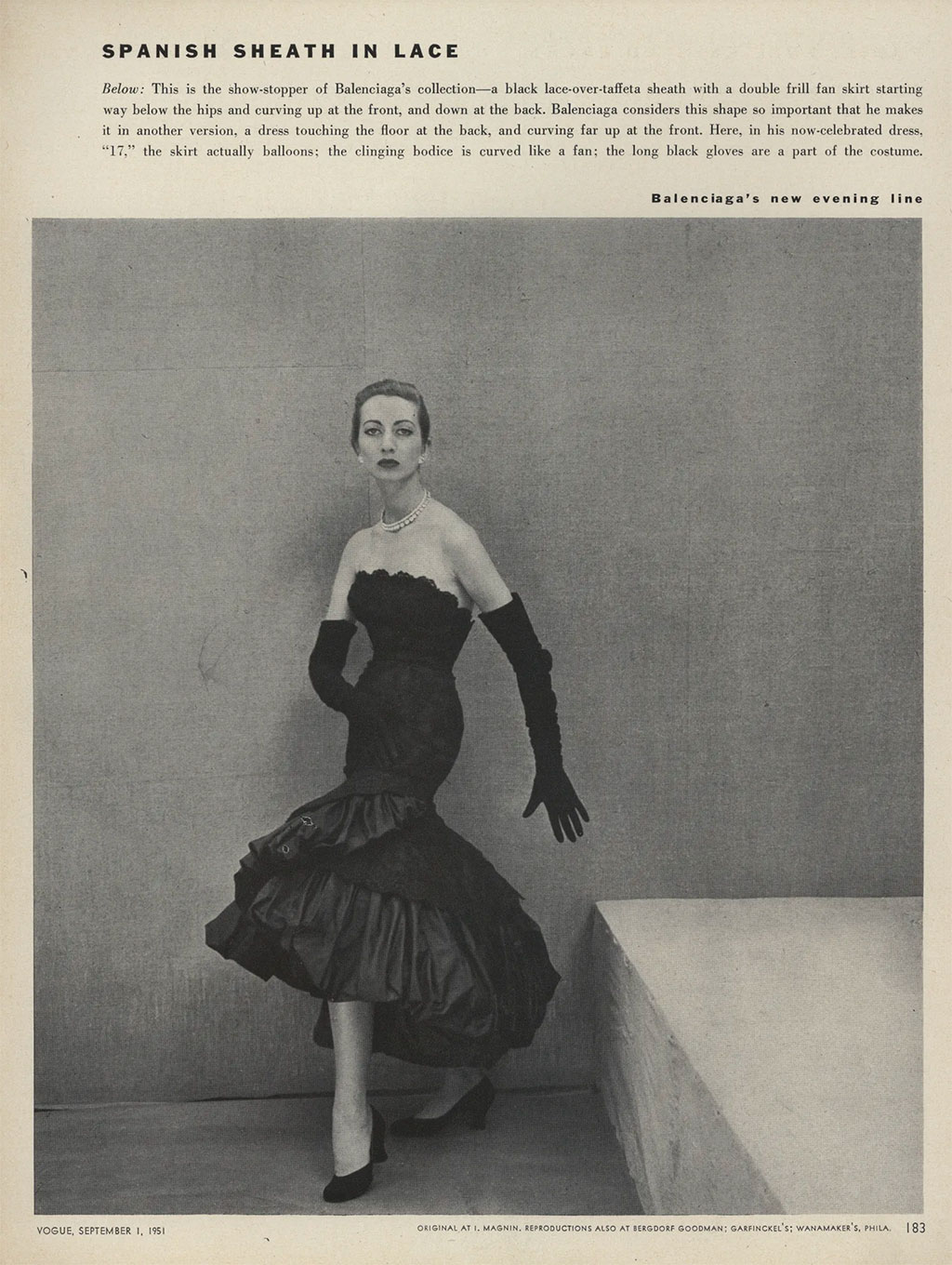

His creations during this period bear testament to his native Spain and its culture. Diana Vreeland—of Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue—said, “His inspiration came from the bullrings, the flamenco dancers, the fishermen in their boots and loose blouses, the glories of the church, and the cool of the cloisters and monasteries. He took their colors, their cuts, then festooned them to his own taste.”

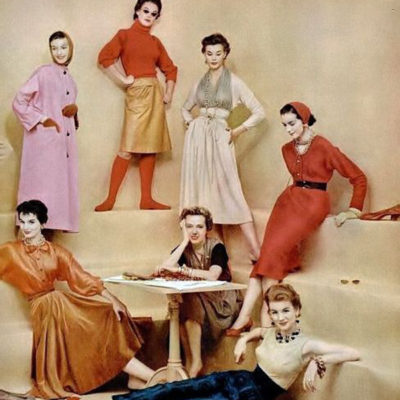

Balenciaga’s “look” epitomized and embraced futurism, and this was groundbreaking. In the 1950s and 1960s, the dominant silhouette was made famous by Dior and his “New Look”—characterized by a cinched-in waist, very full skirt, and rounded shoulders. Balenciaga’s construction methods challenged this as he experimented with architectural construction and developed a new relationship between the body and garment. His garments caressed or stood away from the body as opposed to hugging the figure. By reworking and refining each season’s collections, his radical designs evolved into unique works of art.

A Closer Look at the Garments

Empire waistlines inspired Balenciaga. It became one of his favorites and resulted in many outstanding designs, including the “Amphora” dress shown below. Clever cutting and the use of structured silk created the cocoon-like shape on the back of the dress.

The entire gown was constructed using just two pieces of fabric. From the front, the gown is a fitted strapless sheath. The top of the bodice is slightly padded and stands in relief from the body. From the side, the upper bodice extends around to the back and forms the bow's loose ties. The lower section of the dress drapes to skim the front of the body, but at the back, the excess fabric creates a tucked balloon shape that gives volume over the behind. The inside of the bodice is heavily boned and structured. The full, unlined skirt kicks out at the front hem and balances the hobble effect on the back, allowing the wearer to walk unhindered.

Balenciaga produced a small collection of flounced lace dresses in the late fifties, known as “baby doll” dresses. These designs were controversial, hiding the shape of the woman’s figure when made in opaque fabric. In the example below, Balenciaga both reveals and conceals the body. The sheer, Chantilly lace hangs loosely over a fitted inner sheath, which has zips on both sides to ensure a tight fit. The overdress is very wide, with full gathers at the hip line. Two large black satin bows sit at the middle of the neck and waist. They also added to the Lolita—woman child—theme, preempting the 1960s fashion for short, child-like smocks.

Fashion trends did not dictate Balenciaga’s ethos. His preferred method was to extract specific ideas from each season and to refine and perfect them. Throughout the 1950s, he worked on a silhouette popularly known as the “sack.” The dress below is one variation on this theme, featuring a slim, semi-fitted outline with a round neck, elbow-length sleeves, and a tie front. The upper front bodice section sits close to the body while the front lower skirt is fuller. Pulling on the drawstring ties reduces the fullness at the mid-front. I imagine that these ties extend to the back to keep the front area close to the body. The barrel draping from the back hides the ties and emulates the “Watteau pleats” made famous by the 18th-century painter Antoine Watteau.

Balenciaga After Death: Nicolas Ghesquière

The House of Balenciaga closed in 1968, followed by the couturier's death in 1972. In 1986, the label was re-launched under a series of creative directors to mixed reviews. It wasn’t until 1997 when Nicolas Ghesquière took up the mantle as the natural successor to Balenciaga and changed the house's fortunes. Nicolas Ghesquière’s genius lay in his ability to extract the key aesthetics of the Balenciaga DNA—modernizing an already futuristic look by fusing it with his own contemporary vision.

Ghesquière began his career at Balenciaga by designing suits under license for Japan. At the age of 25, he was chosen to head Balenciaga and put in charge of the brand’s entire image, from clothing and accessories to store design and advertising. His first collection for Spring/Summer 1998 was designed and executed in less than four months. His work for Balenciaga was so harmonious and distinctive that even today, his work is instantly recognizable.

Every season for 15 years, the Balenciaga collection was the one I looked forward to seeing most on Vogue.com. My favorite collection by Ghesquière is from Fall 2008. He manages to combine so many references, including Spanish drama—with a nod to Cristobal’s heritage—to 50’s cocktail dresses. His own vision and taste for futuristic fabrications saw him developing techno surfaces using latex and shantung silk alongside plastic and bonded fabrics—the latter adding architectural volume on structures that would have been supported with boning in Cristobal’s day.

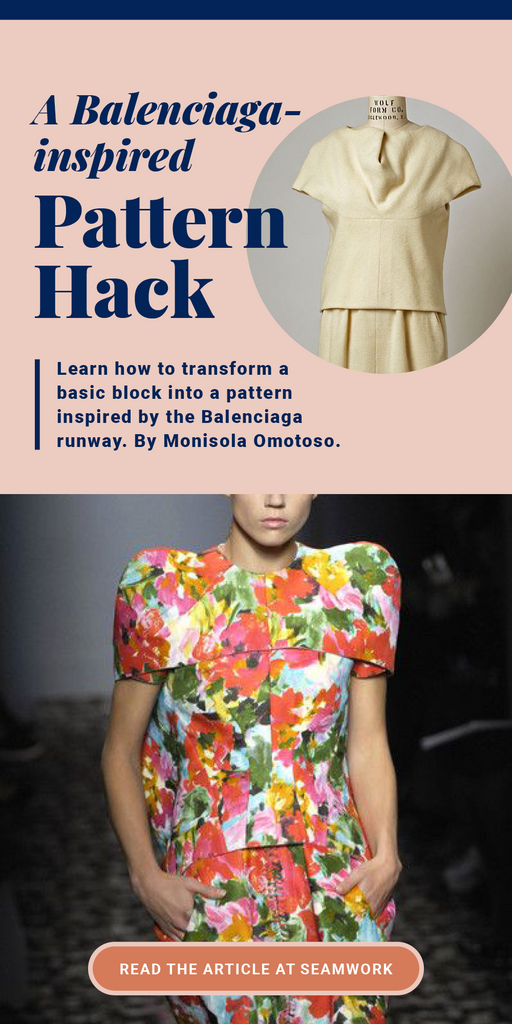

I’ve chosen one of the pieces from the Spring 2008 collection to base my PCDfocusON video. As Ghesquière was so sensitive to the Balenciaga archive, I wanted to highlight the similarities between the 1961 outfit on the left and his reimagining of it in 2008. His use of neoprene fabric adds structure to the cape effect sleeves and adds volume to the bell shaping at the jacket's back. Inverted pleats at the waist give the skirt a gentle structure. Interestingly, if you replicated the outfit from 1961 in hi-tech fabric, it would not be out of place in 2021. The same could be said of most of the key looks from the archive.

A Balenciaga-inspired Pattern Hack

For the PCDfocusON video, I’ll show you how to create a cap sleeve cape similar to the one in the photograph from the Spring 2008 collection.

Key transformations include:

- Shortening a fitted sleeve block and adding fullness

- Combining the sleeve with the bodice block

- Adding a center front opening

The fast-paced fashion arena is always inspired by vintage, classic garments, trying to reimagine them as new iterations. Balenciaga’s ethos of reworking and refining items from his own archive would imply that he had taken his work as far as it could possibly go. However, even he would have been surprised—25 years after his death— by the arrival of the untrained, 25-year-old Ghesquière and how his futuristic vision paired perfectly with his own technical nous. I would hazard a guess that the master had been mastered by Ghesquière.

The final part of this three-part series comes out in next month’s issue.