It is a sunny day in downtown Kansas City, Missouri, where a group of fellow members of the American Sewing Guild and I are being led on a tour. Though the streets are nearly deserted this Friday afternoon, we are walking through what was once one of the largest garment manufacturing districts in the United States. These quiet brick buildings, which are either vacant or have been turned into lofts, once hummed with the sounds of sewing machines.

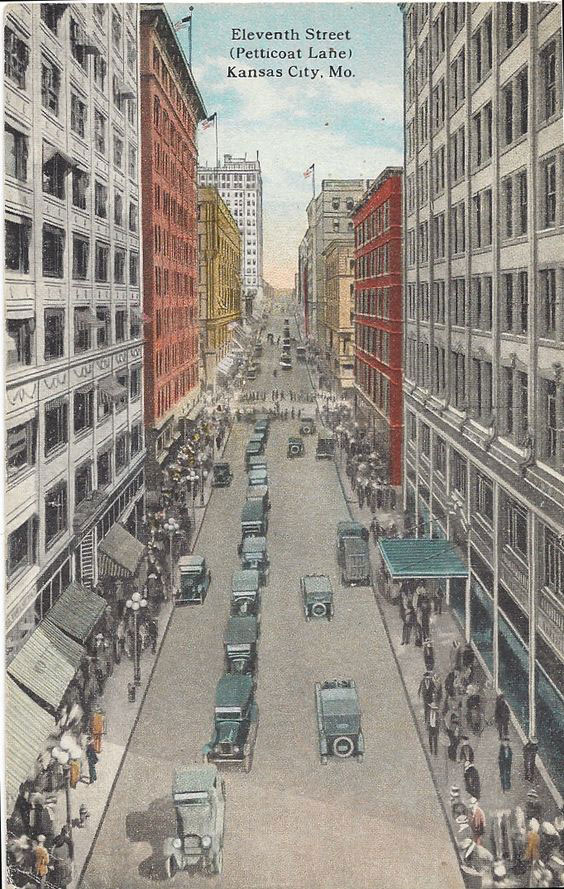

Vintage postcard showing Kansas

City’s garment district, known as

Petticoat Lane.

In the first half of the twentieth century, Kansas City’s garment manufacturing industry was second only to New York City’s Seventh Avenue. At its height, it employed over 8,000 workers at 150 different companies. Our tour guide, Ann Brownfield, the founder of the Kansas City Garment District Museum, tells us stories about the area’s heyday. This building had embroidery machines, that building was a coat factory. She tells us how the cracks in the industry began in the 1960s and widened until the day the last factory closed in the early 1980s. On that fateful day, she stood and watched as tons of patterns, fabric, and notions were thrown out of factory windows into the dumpsters below.

In the ‘90s, textile and garment manufacturing nearly became extinct in America—77% of jobs disappeared as companies moved production overseas. Consumers wanted to spend less on their apparel, and manufacturers looked to China, Mexico, India, and Bangladesh to meet the needs of fast fashion. For many years, it seemed like manufacturing in the US was all but lost.

Recently, the winds of change might be shifting. The booming economies of growing overseas nations have employee wages rising. This, combined with long lead times and steep shipping prices, has made the prospect of reshoring manufacturing to America attractive to companies. At the same time, consumers have begun to demand transparency in their products. The same concerns that led to the rise of organic food have started to trickle over to the apparel industry, where shoppers have become concerned about environmental and human rights issues related to garment production.

There is only one problem—who will sew it? Sewing as a labor skill has been lost. Most schools have dropped sewing from their curriculum, and for many, it can be too cost prohibitive to purchase a machine and learn on their own time. Historically, sewing jobs were mainly filled by women, often immigrants. If manufacturing were to come back to the US, it could be a major economic boon not only to the country but also to an underrepresented demographic.

As the call for production sewing has grown more demanding in the last few years, some organizations have stepped up to fill the void. These visionary startups are connecting the dots between manufacturers, sewing educators, and those who would most benefit from production employment.

Manufacturing a Connection

Raleigh Denim Workshop

The Raleigh Denim Workshop in North Carolina has been making headlines for its efforts to design and manufacture their products completely in the Raleigh area. The husband and wife team of Sarah Yarborough and Victor Lytvinenko co-founded the brand, envisioning a line of classic American-made denim jeans. With no prior design or manufacturing knowledge, the pair started sewing jeans in their apartment in 2007. Today, they house their own factory in Raleigh, are represented in boutiques such as Barneys, and recently opened a flagship store in New York City.

As part of their vision to create a truly locally-made garment, they source over 90% of their materials within 200 miles of Raleigh. But they didn’t just source materials locally, they also looked to their own backyard for experienced apparel industry workers. At 82, Chris Ellsburg, a skilled pattern drafter drafts all of Raleigh Denim’s patterns by hand. Ellsburg, who was once a pattern maker for Levi’s, had been out of work for years when she heard about Raleigh Denim. She approached Sarah and Victor, and though the denim company was still in its infancy and could not afford to pay any employees, Ellsburg chose to work with them until they could. Ellsburg’s experience in pattern drafting and standardizing production techniques helped lay the foundation for Raleigh Denim’s success.

The Makers Coalition

Since talents like Ellsburg’s are rare and demand is increasing for both large-scale and small batch production, industrial sewing training courses are popping up around the country. In Michigan, the need for trained cut and sew workers for both the apparel and automotive industries is so strong that the Henry Ford College added an industrial sewing program to their curriculum in 2014. The $2,000 curriculum, which does have funding options, offers unemployed or under-employed Michigan workers the opportunity to learn a skill that could give them steady employment.

A classroom setup for The Makers Coalition training class.

Meanwhile, in Minneapolis, Minnesota, The Makers Coalition was founded by a group comprised of manufacturers, educators, non-profit organizations, and service providers, who have devised a training program for cut and sew craftsmen. The six-month program teaches beginner sewers everything from threading a sewing machine to working with canvas and leather. After graduation, students have the opportunity to participate in a paid internship program with coalition member manufacturers. The first training session began in 2013 with 18 students. After graduation, almost 90% found employment or continued their education.

The interest in The Makers Coalition program has been so strong that they have recently partnered with the Industrial Fabrics Association International (IFAI). IFAI has formed a Makers Division, which represents any company employing machine operators in the fabrics industry. Together, The Makers Coalition and IFAI are creating targeted curriculum, training programs, and apprenticeship opportunities.

A student learns to work with

leather at The Makers Coalition.

Stitching a Community

The blog Humans of New York recently featured the story of a Russian immigrant who, along with her husband, was forced to flee to America. The brief tale told the struggles of moving to an unknown country where she could not understand the language. Despite the language barrier, she found a position sewing in the costume shop of the Metropolitan Opera. There, she said, as she stitched alongside her coworkers, she finally started to feel like she belonged in her new home.

This contemporary story mirrors ones that happened so many times before. At the start of the twentieth century, a wave of immigrants found their way to New York. Language difficulties created a barrier for many job opportunities, but those who had sewing skills—and many did in those days—found employment in the burgeoning apparel industry. Though the work was hard, often poorly paid, and sometimes dangerous (the deadly fire at the Triangle Shirtwaist factory in 1911 opened the door to safer conditions via organized unions), the apparel industry offered both an income and an entryway into a new culture.

Make Welcome

Sometimes, finding employment in the apparel industry—or any other industry—just is not possible for new Americans. While their husbands go out to work and start to adapt to their country, many refugee women can be very isolated from their new country. They often have to stay home with their small children and because they cannot afford transportation, they do not stray far from home. When Beth Pinckney and Julia Camenisch witnessed the difficulties that refugee women faced in their hometown of Charlotte, North Carolina, they founded the group Make Welcome.

Refugee women learn how to sew at Make Welcome. Each class that they attend is worth $5 off the price of a sewing machine. When they attend enough classes that the machine costs $20, they get to buy and

take home a brand new machine.

Make Welcome teaches sewing skills to refugee women, while its sister program Journey Home provides them with entrepreneurial opportunities to sell their handmade items. The program started with just six women from Burma. Pinckney and Camenisch raised money for sewing machines and materials and also found volunteers to transport the women and watch their children. Today the program has grown substantially and Make Welcome teaches three ongoing classes with women from all around the world.

Clutches and other products made through the Make Welcome program are sold through their sister site, Journey Home.

Initially, Make Welcome was conceived as an opportunity for these women to learn a new skill, practice their English, and create a supportive community. Soon, though, Journey Home was started as an outlet to sell their projects. Currently, the products are only available online but Pinckney and Camenisch are working on a plan to scale the business. Their goal is to provide women with a steady income source that they can use to care for their family.

Empowerment and Employment by

Needle and Thread

Sacred Sewing Room Project

As Make Welcome shows, the power of sewing isn’t just that it provides an income source but also that the act of sewing can be healing. Terry Grahl has a deep understanding of how sewing can serve as a coping mechanism during desperate times. Unknown to Grahl, her mother struggled with depression for much of her life. It was only years later, when Grahl’s mother confided to her that “a sewing machine saved my life,” that Grahl truly understood the darkness that her mother went through and the light that sewing had provided her.

Inspired by her mother, Grahl started the Sacred Sewing Room project. This project was to be a complement to the organization Enchanted Makeovers, which Grahl founded in 2007. Enchanted Makeovers transforms homeless shelters for women and children, many of whom have been abused. The Sacred Sewing Room takes this mission one step further, transforming one room in the shelter into a dream sewing room complete with machines, fabrics, notions, and teachers.

A Sacred Sewing Room, before and after. Each is given a custom painted mural,

sewing tables, machines, fabric, notions, and more.

Beginner sewing classes teach simple projects, enabling the women to make functional items for themselves, their children, or to give as gifts to others. The sewing classes are also teaching the women a marketable skill. And though the Sacred Sewing Room has not enacted an entrepreneurial side to the program, this idea is in the works for the future.

Rightfully Sewn

Jennifer Lapka Pfeifer’s Rightfully Sewn organization is connecting the dots between the needs of at-risk women and apparel manufacturing. Through her work with fashion designers in Kansas City, Lapka became aware of the need for small-scale manufacturing. Meanwhile, through her day job, Lapka was connecting with social services organizations and learned that 67% of at-risk women will return to dangerous situations due to lack of resources.

Realizing that sewing could be the link between her two worlds, Lapka founded Rightfully Sewn. The mission is two-fold: Empower at-risk women by teaching them sewing as a trade and foster the development of local fashion designers by offering them access to trained seamstresses, space, and business mentorship. Recently, the organization awarded scholarships to five designers that will send them through an entrepreneurial business program.

Designer perusing fabric at Rightfully Sewn’s first annual fabric trade show in October 2015. The organization brought in Jay Arbetman of the Sourcing District from Chicago, who has been in the “rag business” since he was 14-years-old. He is very familiar with Kansas City’s golden era of garment design and manufacturing in the last century.

Steve Gibson Photography.

Kate Nickols, a scholarship winner, is the owner of Katie Lee Bridal, which designs custom bridal and special occasion gowns for a national clientele. Nickols not only designs the gowns but also sews them, leaving her little time for marketing and managing her business. Though she has tried finding experienced seamstresses to help her out, Nickols says the search for people who can sew to her standards has been frustrating.

“The lack of qualified seamstresses in the area led me to go outside of Kansas City to look for manufacturing,” Nickols said. “There are many challenges to having your garments sewn in another city, including communication difficulties, additional shipping costs and time. I felt this was not the best method for me and have continued my search locally.”

“I am striving to grow my business,” Nickols continued, “but until I have qualified seamstresses to sew my dresses I cannot take on a larger number of orders. I am greatly in need of a local manufacturing option that will create the dresses while I focus on the business.”

The Future of Cut and Sew Manufacturing

Jennifer Lapka Pfeifer’s vision for Rightfully Sewn is to create a contemporary version of Kansas City’s once thriving garment manufacturing industry. With startups like Rightfully Sewn offering small businesses like Katie Lee Bridal the option to manufacture locally, more cut and sew job opportunities will develop in Kansas City and across the country. As large-scale companies start to reshore their production facilities, sewing is no longer just a hobby—it is, once again, a career.

Kansas City’s monument to the now-extinct garment district. The plaque reads, “This needle sculpture is dedicated to the memory of the wholesale textile and garment industry that flourished in this area from its beginning in 1898… At its peak, the garment business in Kansas City was well known throughout the fashion world, with its products sold in every state in the nation. It became a major area employer, providing opportunities for many newly arrived Americans…”

The future of American manufacturing lies in training its most important asset—its sewers. Reshoring the apparel industry in America will once again provide opportunities for underemployed sectors of our economy, including at-risk women and newly arrived Americans, as it did in the early twentieth century. In 2002, Kansas City erected a monument in the middle of what was once its prosperous garment manufacturing district. A towering needle and thread piercing a large red button, it stands as a testament to the thousands of workers that allowed the city and the fashion industry to thrive. In time, perhaps, the monument won’t be just a tribute to past industry, but also a symbol of ambition for the future of manufacturing in America.