I have a long personal history with the color black. When I came of drinking age in my blue-collar town, black was all I ever wore. It made me feel glamorous and mysterious in the grimy dive bars we hung out in, like a wise-beyond-my-years femme fatale, weary and worldly and destined for better things than the limited opportunities I was surrounded by. It gave me courage and a feeling of invincibility when I pretended to be oh-so-much-more grown up than I actually was. Wearing black allowed the girl I was to feel like the woman I wanted to be.

It goes without saying that I am hardly the first person to be seduced by the power of black clothing; ever since mankind learned how to use the roots and plants around them to dye clothing, black has been an integral part of our collective-clothed identity. Its meaning has morphed and transmuted over the years, from traditional costumes of faith, governance, and mourning, to the nadir of high fashion and then back again.

In fact, so varied and roving is the history of the color black in our species, it might actually be the most powerful color, the color that most clearly represents where our culture has been and where it is going at any given time. From our earliest preoccupations with death, darkness, and survival, through our explorations of mysticism, religion, death, and the afterlife, along our evolution to the “civilized” technological age we inhabit now, black has always been there in some form or another, rife with meaning and whispering our story through its fall and rise in popularity.

Early History

In Roman times, black was first associated with mourning when it was worn by magistrates who participated in funerals. Over time, the tradition of wearing black spread to mourning families, and eventually, throughout the world. The association was natural; we have linked our mortality with darkness since the first humans hid from predators at night time.

As Christianity spread, black became the color of choice for Benedictine monks, representing reverence and humility before God. As Catholicism codified its priesthood regulations, black became a critical part of the sacred uniform, worn during times of penitence, waiting, and in the rites of the dead. However, during this era, it was nearly impossible to create true, pure black tones, since they were among the most difficult to achieve with natural dyeing methods. The blacks worn during this time were actually dark shades of gray.

Queen Elizabeth I, by unknown English artist.

In the fourteenth century, advances in dyeing technology allowed for the production of the first rich, deep-dyed blacks. Philip the Good was the first monarch to exploit the power of black; worn exclusively by him, it set him apart from the brightly robed members of his court. Due to its high cost and association with austerity, virtuousness, and status, black quickly became the favored color of nobility in Europe. For the first time, it symbolized wealth and prestige among the ruling classes.

Black became standard issue for more than just royalty in post-Reformation Europe, as dyeing quality improved and the cost came down. The most common color in clothing—especially portraiture, as it highlighted the individual rather than rank or position—it was a true reflection of the sobriety and piousness of the times, as the Protestant movement rejected the gild, excess, and aesthetic pomp of the Catholic church. The trend became dogma, and remained the most popular color for men’s fashion well into the nineteenth century.

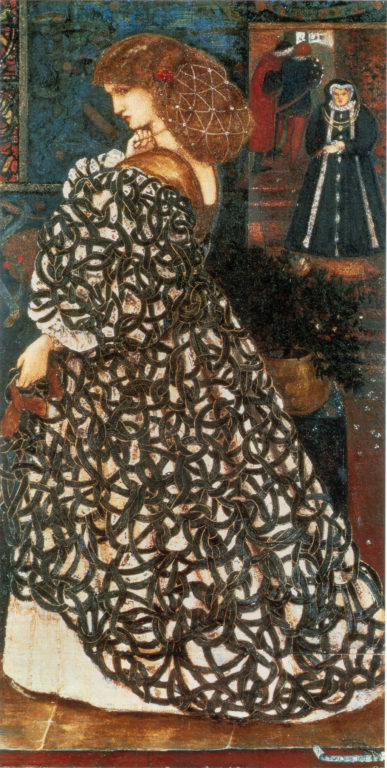

It wasn’t until the age of Romanticism in the nineteenth century that we saw a resurgence of the use of black in womenswear. The goths of their era, Romantic poets, writers, and artists were preoccupied with the supernatural, the occult, and death. Black was the perfect choice for these sensitive melancholics. What better way to accessorize a pale, pallid complexion, or offset an angsty stroll along the moors than a sweeping black dress and cape?

As the century progressed, black receded in womenswear except among the very pious. Once again it became almost exclusively the attire of mourning; women’s defined role in the nineteenth century was largely decorative, and so they dressed accordingly in bright, pastel colors. While men still wore black almost exclusively—this time as a practical measure to hide the appearance of the ever-present soot and filth in industrial cities—it was only the most daring, scandalous, and improper woman who wore black as a matter of course. One of the most provocative and controversial paintings of its time, Madame X by John Singer Sargent, is downright erotic in its celebration of white female flesh against a black, skin-bearing gown. Madame X was transgressive, a symbol of society’s fear of the worldly and sophisticated woman.

Sidonia Von Bork by Edward Burne-Jones.

Madame X by John Singer Sargent.

By eschewing the bright plumage of the hunted for the discreet attire of the hunter, the woman in black is taking on the role of the aggressor. In pastels she’s a target, passive. In black, she’s charting her own course.

– Nancy MacDonnell Smith

The perceived power of black went as deep as the undergarments we wore; in the nineteenth century, white undergarments were mandatory, as they represented purity and modesty. Black undergarments might as well have been a leather gimp suit for all that it shocked Victorian sensibilities. While black underwear is now the most commonly sold, to be a woman in black underthings in the Victorian era labeled you as a shameful deviant.

Post World War I, black re-emerged, both as a collective symbol of grief over the horrors of war, and a practical choice for life in grimy, dusty cities. Wearing black simply felt modern, like the strike of Helvetica upon a white page, the silhouette of a black Model T Ford on the road, or the stark contrast of a dark smokestack belching smoke against the sky. In fashion, the color black represented progress. With the swinging flapper styles of the Roaring Twenties, it was refined and elegant, the favored choice of many designers, especially Coco Chanel.

Early 20th Century

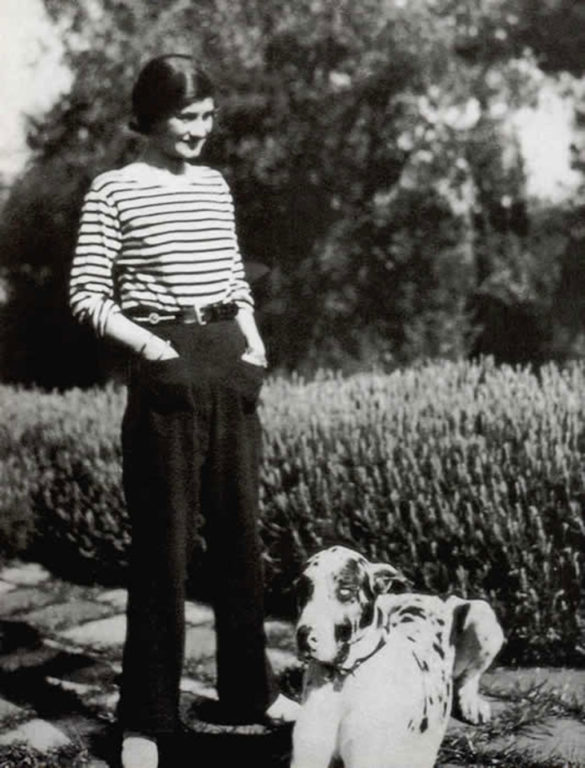

Chanel is widely attributed with creating the little black dress, but it is more likely she simply popularized an existing idea. Chanel’s mission was to bring comfort, practicality, and elegance to women’s fashion. She loved black for its chic purity and simplicity. Of course, not all designers were as enamored with the shade, and Paul Poiret, king of Belle Epoque bohemian fashion—which by this time was terribly out of fashion—was among them. As the famous story goes, when he happened to cross paths with the black-clad Chanel he asked her, “For whom, Madame, do you mourn?” Her reply? “For you, Monsieur." What a burn!

Coco Chanel is widely credited with the popularization of the little black dress.

Black remained extraordinarily popular in Western dress until the 1960s, used frequently by the couturiers of the time, first by Dior, later by Givenchy and Balenciaga. Black was slimming, mysterious, and dramatic, and wearing it marked your entrance into womanhood. As Christian Dior said, “You can wear black at any time. You can wear it at any age. You can wear it on almost any occasion. A little black frock is essential to the woman’s wardrobe.”

Audrey Hepburn as Holly Golightly in Breakfast at Tiffany's.

Some of the most iconic fashion moments in the 1940s and 1950s are proof of the iconic nature of black. Who can forget Audrey Hepburn in Givenchy noir in just about every movie she made? Or Rita Hayworth as Gilda, the femme fatale in a curve-hugging black gown? In high contrast black-and-white cinema and photography, black was the color of the period.

Modern Fashion

"Black suggests a uniform chicness that transcends mere fashion… It is built on refusal. It doesn’t give the wearer many props but rather lets her own self shine." - Nancy MacDonnell Smith

Of course, black is always loaded with meaning, depending on who is wearing it and when. The favored hue of the 1950s-era beatnik, a black turtleneck and beret signified artistic and intellectual seriousness. To the rebels and motorcyclists, a black leather jacket was an anti-establishment banner. Black has always been able to straddle numerous meanings; the power it has to be both simultaneously rebellious and the very definition of traditional chic is part of its enduring power.

With the advent of pop, psychedelic, and youth culture in the 1960s, the color’s popularity waned, except as a political statement among groups like the Black Panthers. It wasn’t until a decade later that black was once again at the forefront of style.

“I work in black because it affirms, designs, and styles. A woman in a black dress is a pencil stroke.” Yves Saint Laurent

When punk music emerged and exploded on the cultural scene, it brought with it a dark, brooding, nihilist fashion identity. The epicenter of punk fashion, Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren’s London shop, SEX, was the go-to place for latex bondage gear and anarchy tees for taste-makers like the Sex Pistols, Chrissie Hynde and Siouxsie Sioux. Punk’s influence ran deep over the following decade, and bled into the 1980s New Romantic, post-punk, goth and industrial scenes. In the 80s you couldn’t swing a cape without hitting at least ten melancholic teenagers, all grooving to their own dark beats while shrouded in layers of black.

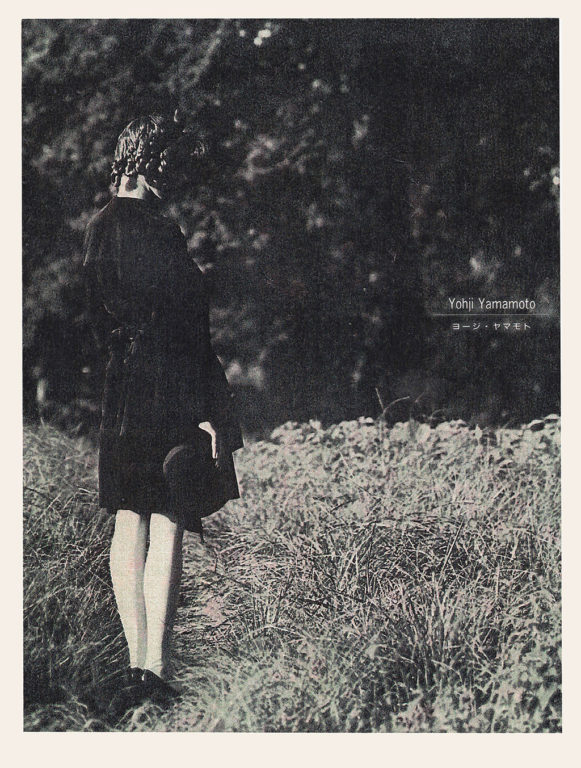

Like most underground trends, black naturally filtered into the higher echelons of fashion. Helmut Newton’s darkly glamorous portraits were practically fueled by powerful women in black, as was the fashion of Azzedine Alaïa. As the 1980s progressed, it was also the palette of choice for the avant-garde. The androgynous, oversized silhouettes favored by Yohji Yamamoto were exclusively black, because, “Black is modest and arrogant at the same time. Black is lazy and easy—but mysterious. But above all black says this: I don’t bother you—don’t bother me." As for the uniformly dark, deconstructed, asymmetrical styles of Comme des Garçons, designer Rei Kawakubo explained, “I work in three shades of black."

Yamamoto and Kawakubo’s powerful influence are felt now, decades later, in the similarly severe, modern, and avant-garde collections of Rick Owens, Gareth Pugh, and Ann Demeulemeester, all designers who work almost exclusively under cover of darkness.

“Black is not sad. Bright colors are what depress me. They’re so… empty. Black is poetic. How do you imagine a poet? In a bright yellow jacket? Probably not." – Ann Demeulemeester

Over our long history of fashion, black has played a critical role in defining us. No other color can encapsulate the contradictions and complexities of human beings quite like black does. What other hue is capable of being both severe and demure, chic and anti-fashion, seductive and conservative, common and avant-garde, all at the same time? Only black, in all of its mystery, depth, elegance, drama, and simplicity seems up to the challenge of eloquently defining all that we are. Through its history we can trace our own, as we move from orthodoxy to rebellion, from pre-history to modernity, from darkness to light. In its very darkness we are reflected.

In the end, what better color to have in your closet and at your disposal? There is a reason it is the favored color of fashion editors and designers, and why trend pieces are always trying to proclaim the “next black." It will be perennially in style for as long as we keep draping ourselves in fabric. We should take a page from Dior, Chanel, and Madame X, and all aspire to make and own those critical black wardrobe staples that will serve us time and time again; the little black dress, workhouse trousers, a classic silk shirt, a simple maillot swimsuit, a glamorous lace lingerie set, a soft layer of linen to get lost in. You’ll find yourself in very chic, timeless company.