This is the unlikely story of my sewing and textile practice, for which I have to thank Antarctica, my dad's sewing box, and the priceless gifts of Aboriginal creative knowledge bestowed on me by my friend Tiriki Onus.

My dad taught me to sew and instilled in me the innate adventurousness of his character when it comes to creative projects, but as I thought about where I draw inspiration, it became impossible to continue without acknowledging the culture of craftsmanship of the traditional custodians of the land on which I live, work, and sew—Australia's First Nations People—the world's oldest continuing culture.

I am so grateful to have had the privilege of learning techniques that Australia's First People have been sharing for thousands of generations and become the first generation of my family to learn sewing techniques outside of the matrilineal norm.

Learning from Thousands of Generations of Textile Arts

Yorta Yorta Dja Dja Wurrung (Northern Victoria, Australia) man, Tiriki Onus, is Head of the Wilin Centre for Indigenous Arts and Cultural Development at the University of Melbourne.

I met Tiriki when I was appointed a junior role in the Faculty of Fine Arts and Music's External Relations department. Initially convinced that our paths were unlikely to cross given his seniority, I soon discovered that his gregarious personality, warmth, and good humor had its own orbit. Despite the significance of his role in the community and at the University, he was approachable and humble. After I accidentally let slip my passion for horror films and distasteful sense of humor, we became firm friends.

Tiriki took me to his grandmother’s Country—Yorta Yorta Country, incorporating greater Shepparton and Mooroopna and stretching into New South Wales across the Dhungala (Murray River)—and shared his experiences working with sewing and weaving with his community.

Fiber work in the Western world is still largely seen as being a woman's craft. We even use minimizing language to talk about it as “craft” instead of art. We talk about crafting practice, and we don't realize that, on Aboriginal land, this strange gender divide is contrary to tradition.

"Many of our practices, particularly many of our weaving practices, were entrusted to men," says Tirriki, "but more recently, many of our community don't engage with practices because they think it's not masculine”—a very western hangover from the Industrial Revolution.

Nets Were Woven by Men, but Maintained by Everyone.

"Up here on Yorta Yorta country, our practice of net weaving is a knowledge system that belongs with men. It doesn't mean that other people don't weave, but our nets were made predominantly by our men, and then they were handed over to the community for everyone to use, and to own, and they were maintained collectively by everyone." Those stitches, those pieces of knowledge, became a shared part of the community.

"I see quite a number of Aboriginal men of all ages who are concerned about engaging in practices like weaving, even making Biganga [possum cloaks], because they don't know where they sit in this whole world of sewing, and stitching."

Tiriki teaches cloak making using possum skin, a once everyday item for Koori Aboriginal people in southeastern Australia. Scored and painted with ochre, possum skin cloaks tell stories of their owners, clan, and country. He said that, for Koori people in southeast Australia, there was no more significant and defining work of art than the possum skin cloak. “It was given to you at birth, and as you grew, it also grew,” he wrote in an application for the inaugural Hutchinson Indigenous Fellowship (HIF) at the University of Melbourne.

Reviving the Art of the Possum Skin Cloak

"Auntie Glenda Nicholls revived our practices of knitting and weaving here in Victoria. She's a Waddi Waddi Yorta Yorta Ngarrindjeri woman, and has done extraordinary things for our fiber work community. She was passionate about sharing her knowledge of fiber craft with Aboriginal men,” says Tiriki.

"Only three men turned up to Glenda's men's sewing workshop—myself and the two people I talked into coming. It was sad because here was someone who had an extraordinary knowledge and practice, and she wanted to share with the community, but lots of the men felt it wasn't their place. I felt really sorry for those men because this was a weaving practice that had been taken away from them."

Do as I Do, While I Say it

Auntie Glenda Nicholls had a unique way of teaching her pupils. Rather than sitting them down and giving instructions, she would begin to tell stories while her hands worked. The rhythm of the movement and her voice as she worked were reportedly hypnotic, and it was in this way that Tiriki imparted some of those techniques onto me, one happy afternoon on Yorta Yorta country.

And upon reflection, it was that same way that my dad, Peter, taught me to sew. That is, by not teaching me at all—rather, sitting in his green corduroy armchair, animatedly wrestling with a needle from his self-made leather sewing kit.

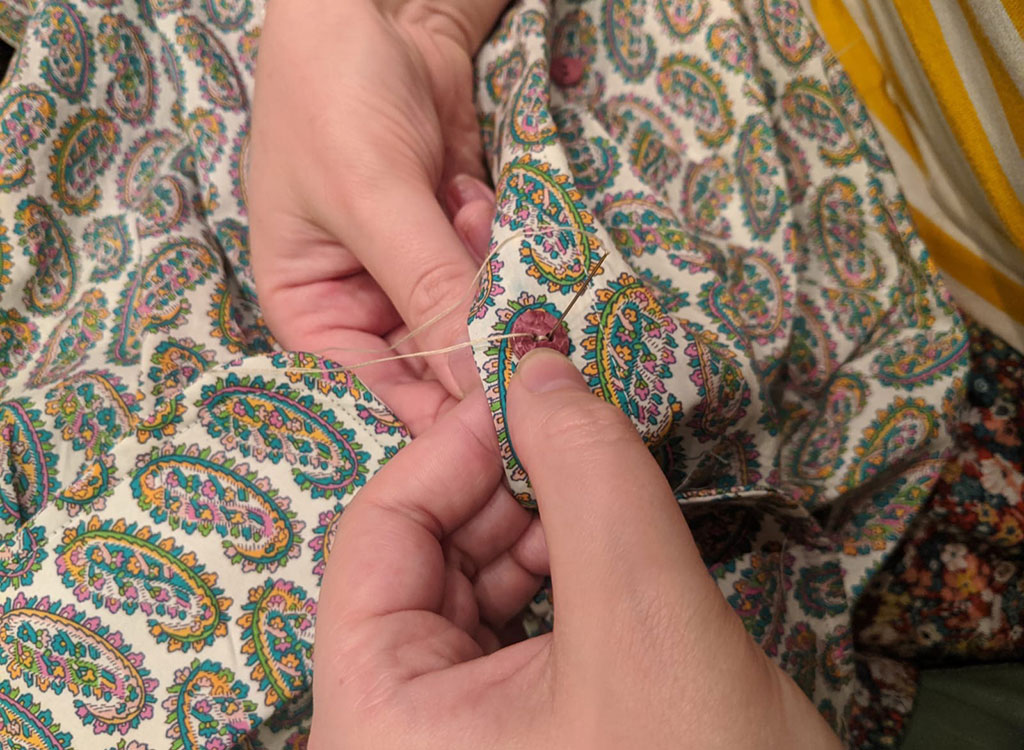

Learning to sew a blanket stitch with sinew from kangaroo tail, to weave baskets and net traps—this is precious knowledge, once belonging to Aboriginal men and communities, that has become a part of my creative practice.

And upon reflection, it was that same way that my dad, Peter, taught me to sew. That is, by not teaching me at all—rather, sitting in his green corduroy armchair, animatedly wrestling with a needle from his self-made leather sewing kit. "My buttons never come off!" he boasts when I press him about sewing.

“Like riding a bike,” he says, "sewing is a life skill that we all should have.” This is a sentiment shared in Tiriki’s family—we both grew up in a household where sewing felt like basic human knowledge that anyone should have.

“Like riding a bike,” he says, "sewing is a life skill that we all should have.”

Learning to Sew Outside of the Matrilineal Norm

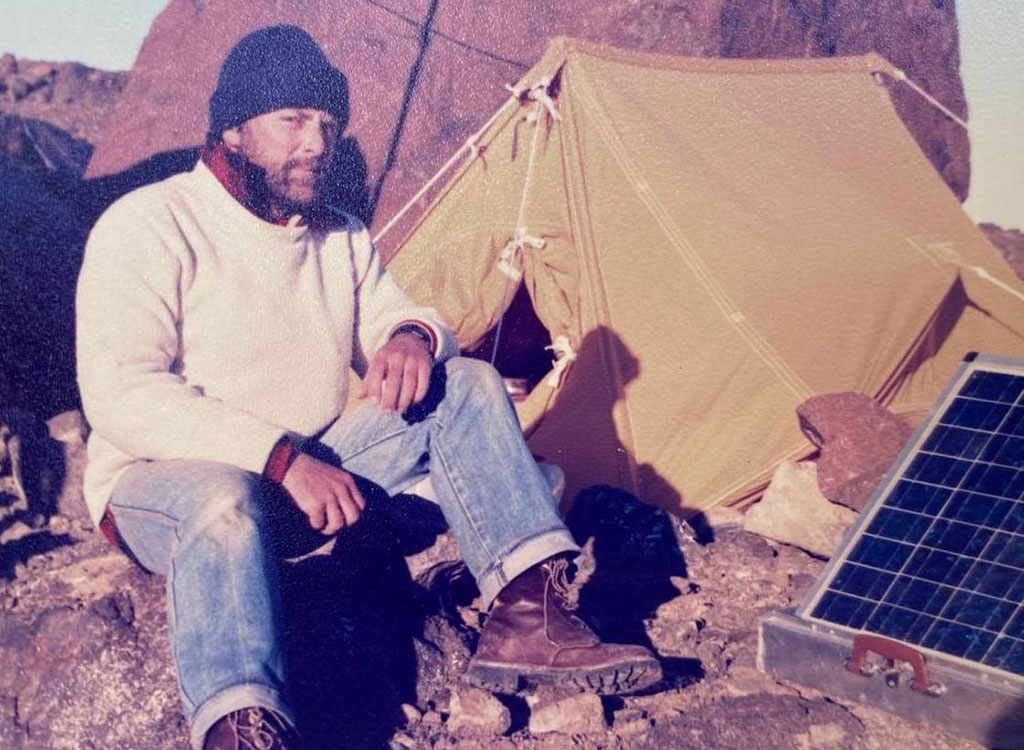

Dad is an adventurous man and took his sewing kit everywhere—even to Antarctica, in 1987, where he and a crew of scientists lived and worked in dome-shaped tents on the tundra. "When you're watching your roll of toilet paper blow away across the arctic, you've got more important things to worry about than holes in your socks,” he reminisces.

His workwear constantly needed mending—darning socks was part and parcel of daily life. The standard-issue Australian National Antarctic Research Expedition (ANARE) brown boots weren't sufficiently durable to withstand the extreme conditions: "I had to use the screws from our ration boxes to reattach the soles of my boots,” he said.

I love to create utilitarian clothes. Strong, flat-felled seams. Reinforced knees and elbows. Sashiko embroidery repair that meets beauty and practicality. Just like Dad, nailing the sole of his boot. Just like Tiriki, patiently stitching possum skins to wrap his newest daughter.

I feel so fortunate to have these men as sewing role models. I love to create utilitarian clothes. Strong, flat-felled seams. Reinforced knees and elbows. Sashiko embroidery repair that meets beauty and practicality. Just like Dad, nailing the sole of his boot. Just like Tiriki, patiently stitching possum skins to wrap his newest daughter.

The main difference between Dad and I is that I'm a selfish sewer. I don't believe dad ever sewed anything for himself—whether he was making curtains, quilt covers, toys for me, or taking up a school-dress. I have taken the opposite tack and am now on a mission to sew myself a wardrobe so vast I'll probably be buried under it.

But there's an adventurous something-or-other about my sewing that I can only afford to the way that I learned, and the wonderful men who have taught me. There is nothing masculine, feminine, or otherwise about it. Sewing is meditative, joyful, practical, indulgent—a wonderful opportunity for introspection and reflection. Sewing creates culture and community. And between generations, one thing remains the same—neither dad's nor my buttons ever come off.