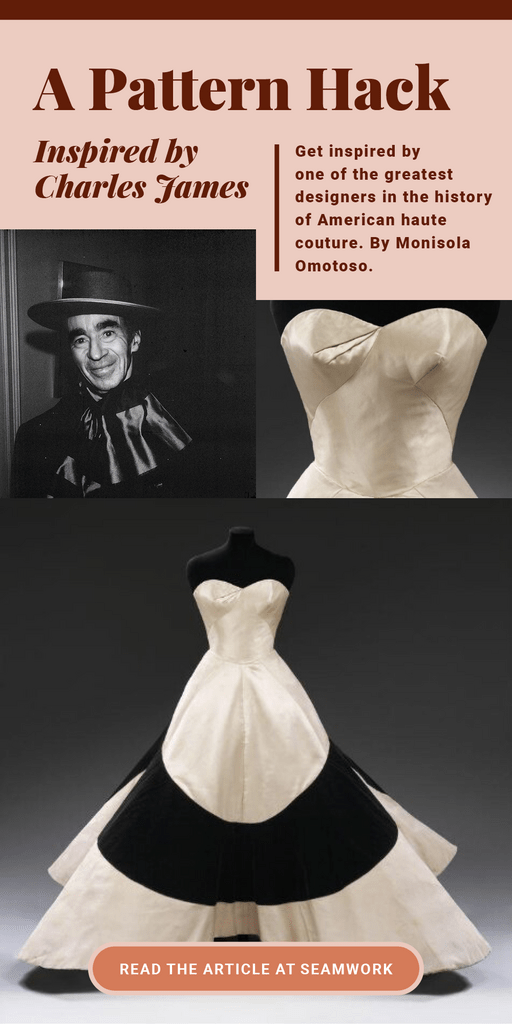

I have decided to go slightly off-piste from my previous two articles—where I discussed the founders of Delpozo and Balenciaga and the new designers who took over their brands. In the final part of this series, I’m writing about a fashion house that ended with the designer’s demise.

A Couturier for Couturiers

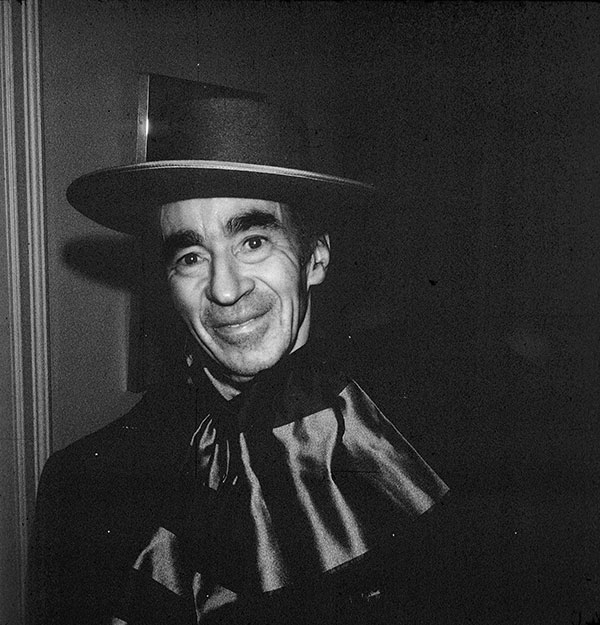

The title genius is not usually bestowed on mere fashion designers. Charles James (1906-1978) earned this label through innovative, complex fashion design focused on pattern cutting skills and mannequin developments to support his sculptural creations.

His work influenced many great designers, such as Christian Dior (1905-1957), who acknowledged James as the greatest couturier of his age—and inspiration for Dior’s infamous New Look. James also influenced Halston (1932-90) and McQueen (1969-2010) and continues to influence designers in the 21st century. For this reason alone, his brand should be a household name—his contribution to fashion remembered by a wider audience. However, the opposite is true.

Self-taught, Charles James earned the epitaph of couturiers’ couturier when his clientele included Chanel and Schiaparelli—an achievement testament to his talent. As a perfectionist, he worked for years on refining certain seam lines and shapes, using rigorous engineering to express his art. As a controversial figure with an exuberant artistic expression, his temperament overshadowed his ability to make good business choices. Subsequently, without any business acumen, James died penniless and bitter.

His temperament overshadowed his ability to make good business choices. Subsequently, without any business acumen, James died penniless and bitter.

Yet, as Mrs. William Randolph Hearst Jr. once said of him, “So we must forgive geniuses their transgressions. Remember them only by the beauty and inspiration they give us, their legacy to us.”

The Life of Charles James, A Sartorial Structural Architect

Born in England to an English-army-officer father and a wealthy Chicagoan mother, James went to Chicago to work after expulsion from Harrow School—an expensive boarding school for boys—for a sexual escapade. A family friend hired him for a position in an architectural design department. It was here that James acquired the mathematical skills that he later used to enable his clothing designs.

James started his fashion career as a milliner in 1926. While his millinery only lasted a few years, he acquired skills to use throughout his career. In 1928, James moved to Long Island, where he presented himself as a “sartorial structural architect” and began his first dress designs.

He began to focus on women’s couture, ready-to-wear, and accessories between 1930 and 1978. Despite having no formal training, James is recognized as one of the greatest designers to have worked in America’s haute couture tradition. His fascination with complex cuts and seaming, creating key design elements throughout his career: figure-of-eight skirts, wrap-over trousers, body-hugging sheaths, ribbon capes and dresses, spiral-cut garments, and poufs. These, along with his iconic ball gowns from the late 1940s and early 1950s, formed the corpus of his work.

A Closer Look at Three Pieces of His Work

James was so keen to ensure his legacy that he persuaded important clients to donate his designs to the Brooklyn Museum. His definitive body of work is now housed in the Metropolitan Museum after being transferred there in 2009—and is the most comprehensive collection of a fashion designer’s work of any museum.

The three items I will be discussing in this article are a selection chosen from over twenty of my favorite designs. What I love about James was his fondness for reusing, reworking, and refining his designs. As a couturier who worked with regular clients, it wasn’t always necessary to design an item from scratch. His sustainable aesthetic was admirable.

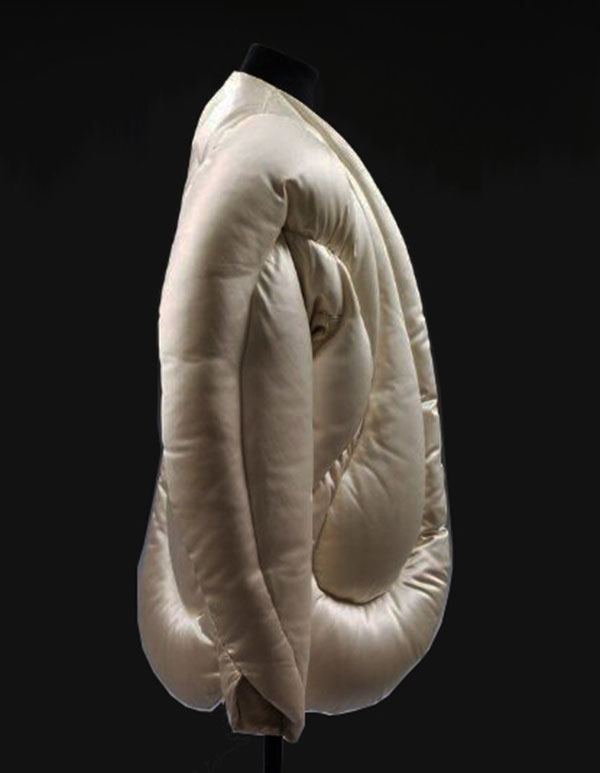

The First “Soft Sculpture”

I first discovered this piece on a visit to the V&A in London as a teenager just before I started my fashion education. It is my idea of a perfect garment that needs no improvement. It was not only one of James’ most important pieces; it is also celebrated as one of the most iconic pieces of 20th-century fashion.

I was stunned by several things about this piece—its shape was so of-its-time, yet it evoked the future of fashion. It’s a precursor to the puffer jacket. The Surrealist artist, Salvador Dali, on seeing it, proclaimed it to be the “first soft sculpture.”

Here is a closer look at this piece—a hip-length, collarless, edge-to-edge evening jacket with long sleeves. It was constructed in a series of quilted curves in the same manner as an eiderdown (a quilted duvet). This garment is so thick that it could impede movement, but James resolved this by diminishing the padding’s depth around the neckline and armholes.

The front, left, and right panels were quilted separately to make this jacket, following a scroll pattern that formed two hearts at the center back. The separate panels were then stitched together down the shoulder seams. A gathered dart forms the sleeve head and extends down the back of each sleeve to the hem. The large gusset underneath the sleeve in the underarm area is typical of a grown-on sleeve and allows for more movement. There are eighteen darts inside the front-facing to make the jacket fit close to the body.

James longed for this jacket to be translated into other materials—an expensive version in kid leather, for example, or a mass-market example in nylon stuffed with kapok for motorcycle- or ski-wear. It is a triumph in both cut and construction, a testament to his extraordinary technical ability as a pattern cutter. James described his “pneumatic jacket” as a “technical challenge and fantasy,” adding that it would likely have absolutely no importance within the fashion industry due to the difficulty of reconstruction.

A Fishtail Mannequin

My second choice of garment is the iconic La Sirenne dress, an incredible design that defies classification. Azzedine Alaia, whose designs rose to fame in the 1980s, was inspired by this dress and created a knitted version. While it was a clever idea to create it in an entirely different fabrication, it was so obviously based on James’ version.

As a sculptor of fabric, it was important to James that he had mannequins fit for purpose. It’s usual for couturiers to use regular mannequins that are then padded to match the client’s unique measurements. James, however, took this process further by creating a form with a fishtail exterior that would enable him to sculpt the lower section of the dress. Influenced by the drapery formations of the 1870s and early 1900s, La Sirenne was formed in three sections—bodice, sleeve, and skirt.

The dress is fitted close to the body until it reaches just below the hips. The mannequin’s fishtail allowed James to drape the fabric with some movement below the knees, giving the tucks more structure and control. Without the fishtail base, the dress would have collapsed.

The Iconic Four-leaf Clover Evening Dress

James identified the Four-leaf Clover evening dress as his greatest achievement. The design represented the amalgamation of “many parts from which a whole series of designs had been made…It seemed to me to be somewhat of a thesis.”

Many iterations of this design were made for various clients over the years. James used shapes to aid fit and create unconventional forms, concealing the shapes within the garments’ construction. His work often included variations on the circle. A circle is not an untypical shape in pattern cutting—but he used geometry rather than simply draping shapes around the mannequin.

Cutting a small circle out of the center of a larger circle creates a basic skirt. The Four-leaf Clover dress uses a “circle within a circle,” or “meta-circle” shape. The skirt’s outer circle is actually a square with curved edges, and the inner circle is the shape of an eclipse. When attached to the dress’s lower body, it shows similarity to a conic section—the curve created by the intersection of a plane and a cone. The plane of the outer skirt isn’t perpendicular to the central axis of the cone. It’s attached at an angle, causing the inner circle to change shape to an eclipse.

A Pattern Hack Inspired by Charles James

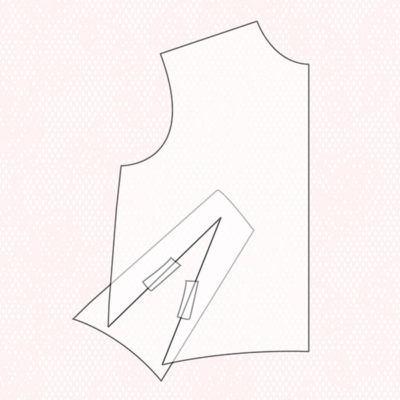

I have selected the Four-leaf Clover dress bodice for this Pattern Cutting Deconstructed video demo of a bustier. It’s a suitable design for a more confident dressmaker to transform into a pattern, starting with a basic bodice block.

This video includes the following transformations:

- Turning a bodice block into a bustier

- Eliminating the waistline and lengthening the garment to sit on the hip

- Manipulating darts asymmetrically

- Adding a side slit

An Artist Without a Business Manager

When I think of James’ life, I am reminded of the lives of artists such as Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, geniuses of their time who relied on their benefactors—the church—to continue producing their work. James also relied on his wealthy client’s funds to live the life of a creative. If only one of them had offered support by suggesting the appointment of a business manager. This would have transformed his life, allowing him to create and earn money while doing so. No one has taken up the mantle from Charles James, which is a great pity considering his extraordinary talent.