If you live in a rainy climate, you treasure the rain gear in your wardrobe. However, you also know that finding a stylish rain jacket in the store can be challenging.

But is it hard to sew a rain jacket?

It’s a lot of work but also a very rewarding project. If you’re curious, here is a round-up of resources for making your own rain jacket. You’ll learn about different types of fabric options as well as the notions you need to keep your seams sealed and your clothes dry.

While this article celebrates the new Lou jacket pattern—our 200th Seamwork pattern!—you can apply all this knowledge to any other outerwear pattern.

Ready to sew some rain gear?

Shopping for Waterproof and Water-resistant Fabrics and Notions

Your waterproofing adventures start with your fabric choice. Before reading about all sorts of water-resistant options, here are a few cautionary tales when shopping for fabric for rain jackets.

The fabric might be waterproof, but not intended for garments. You’ll notice that many outdoors fabric specialists sell fabric for boats, tarps, and outdoor furniture. These fabrics will likely be very stiff and lack the drape you need to sew a garment that will hang nicely on your body.

The fabric might be marketed as waterproof, but it’s really water-resistant. This is actually true for all rain gear, even the professionally sewn Gore-Tex you’ll get at your favorite store. No fabric will be completely waterproof if it gets soaked for prolonged periods of time. So when looking for fabric, it’s all about finding the one that will buy you enough water resistance for your goals, like going on a rainy hike or running errands. There are waterproofing ratings out there, and you can find some ratings on major outdoor gear sites like REI.

Pay attention to the Durable Water Repellent (DWR). Your waterproof fabric is likely treated with a repellent to help all the little raindrops bead up and roll right off your shoulders. This repellent will wear off over time, and you must reapply it. Even ready-to-wear brands like Patagonia durable water repellent spray encourage you to reapply and repair your gear. Here is an example of durable water repellent spray from Seattle Fabrics.

Water-resistant and Water-repellent Fabrics

Water-resistant fabrics will do their best to keep you dry. They make it hard for water droplets to penetrate your garments, but they aren’t completely waterproof.

Water-repellent fabrics also resist water but aren’t entirely waterproof. They’re just treated to be a bit hydrophobic!

If you’re dashing out to run errands in the rain or going for a walk in a slight drizzle, you will be fine with water-resistant or repellant fabrics. They are pretty good at wicking away the rain, and they breathe well, so you won’t get sweaty.

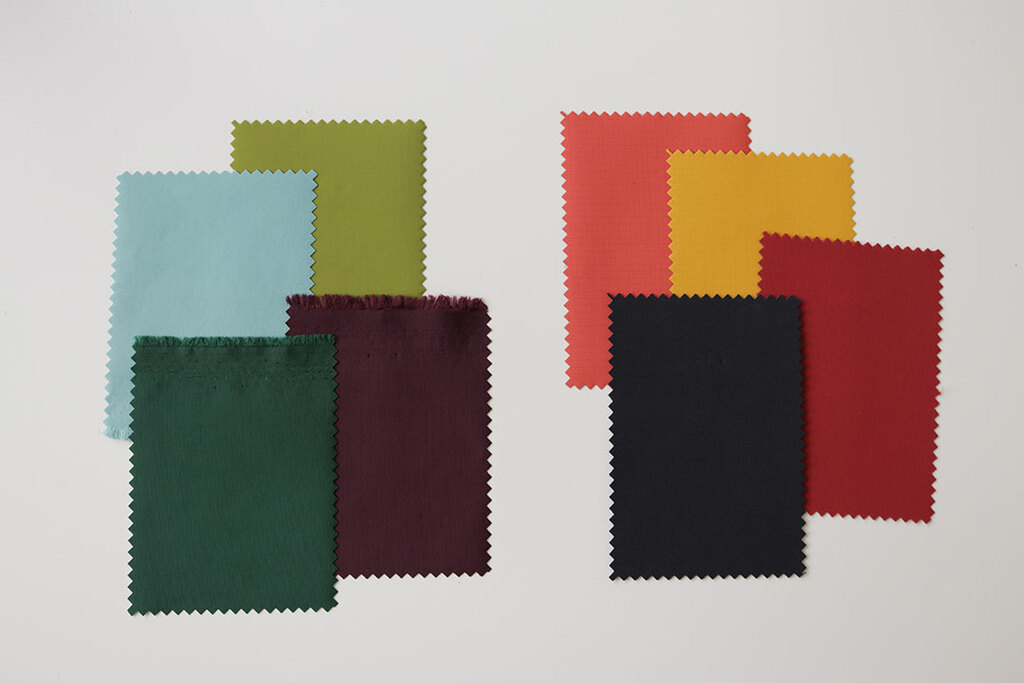

Here are some examples of water-resistant and water-repellent fabrics.

-

Laminated Fabrics. These are fabrics that have been bonded with a waterproof layer. The water-resistant layer coats the wrong side of the fabric, which helps keep water out and adds a bit more structure to the drape. So are laminated fabrics totally waterproof? Not always, but they do offer great water resistance. Laminated cotton is available in some really fun prints, so aesthetics might be worth the sacrifice. -

Fleece. You’ll notice that many outdoor garment fabrics appear to be fleece. The trick is getting a very dense fleece specifically marketed to be water-resistant. Some technical fabrics, like softshell, are often backed with fleece, so they feel comfortable against your skin, and there’s no need to sew a lining. -

Nylon Taffeta. This fabric is often treated with a DWR to make it water-repellent. You’ll find nylon taffeta on your umbrellas, so you know it works! -

Oilskin: Oilskin is a water-resistant fabric you’ll find throughout history, like on the traditional and oh-so-stylish Sou’wester rain hats that are longer in the back and shorter up front. Oilskin is created by coating cotton or linen with a mix of wax and oils, creating a water-repellent barrier. You’ll find dry and traditional oilskin. Dry oilskin has an extra treatment to eliminate any residue you might find on traditional oilskin. When sewing with oilskin, you might want to add a protective barrier, like cotton or lawn, to prevent residue from coming in contact with your skin. Is oilskin the same as oilcloth? Historically, yes, but modern, commercial oilcloth is often a vinyl-coated cotton and works better for tablecloths than garments. -

Ripstop Nylon. Ripstop is woven in a way that creates a tight seal to prevent moisture from creeping in and strengthens the overall integrity of the fabric, so it’s less prone to ripping and tearing. If you look close, you’ll see little squares that indicate the weaving pattern, similar to how you’ll spot a twill pattern in denim. (Just a note about nylon. Nylon isn’t waterproof on its own, but you will notice it is an ingredient in many fabrics you can use for rain gear, like Cordura nylon.)

-

Softshell: This is a great option for a casual rain jacket that you won’t wear in a total downpour. Softshell gives you more protection than fleece but not as much as waxed canvas or oilskin. It’s usually made from woven nylon or polyester, perhaps with a bit of elastane so that it stretches to move with you. It’s often backed with fleece, so sewing a lining is unnecessary.

-

Silkara: You know that water-resistant cape they give you to wear at the salon? It might be taffeta, but it also might be Silkara. Silkara is breathable and lightweight, made of nylon and polyester, with a great drape and sheen for garments.

-

Waxed Canvas. Like oilskin, waxed canvas is a canvas treated with wax to create a physical, water-repellent barrier. The cotton fibers in the canvas drink up the wax, making themselves watertight. Waxed canvas is breathable, very durable (even more so than Gore-Tex), and comfortable to wear. You need to continue treating it with wax to maintain water resistance, and there is a chance that residue can spread to your lining. It’s easier to sew with pre-waxed yardage, but you can wax your own fabric. Here’s an article that will help. -

Wool: Have you ever donned a felted wool rain hat before? Wool is naturally water-resistant, boiled wool even more so.

Waterproof, Non-breathable Fabric

You might have seen some very sleek, rubber-looking raincoats out there. Think about a classic bright-yellow slicker you wear out fishing on a boat. This fabric might look retro and stylish, but the drawback is that you will get sweaty if you are active.

Waterproof non-breathable fabrics keep moisture out, but they also keep moisture in. So you won’t get wet from the rain, but you might get damp from perspiration.

Many of these fabrics also fall into the cautionary tale about drape. They are often stiff, which might not work with your pattern’s design. You might see an exception with childrenswear, as kid’s clothes don’t take as much yardage, so they are more forgiving with a stiff drape.

Examples of non-breathable waterproof fabrics include:

-

Neoprene. While neoprene keeps you cozy and dry if you’re swimming, it will also trap sweat if you use it for a jacket. Breathable neoprene is available but less likely to be waterproof. -

Vinyl-Coated Polyester: This fabric is rigid and heavy-duty, made by coating a polyester layer with vinyl, providing a waterproof barrier. -

Oilcloth. This vinyl-coated fabric is better suited for your picnic table—or a waterproof bag! You might see some thrift flips made from oilcloth tablecloths. It’s not traditionally used for garments, but hey, get creative!

Waterproof, Breathable Fabric

Waterproof breathable fabrics keep you dry, letting moisture (aka your sweat) escape from the inside. So you can get that bright-yellow-slicker look but with a drape that’s suited for garments. Waterproof breathable fabrics are designed to play the moisture game.

How do they do this? It’s all in their membranes. Their pores are smaller than raindrops, making it harder for water droplets to get in until the fabric becomes totally saturated.

Waterproof breathable fabrics are usually made out of two or three layers. The first (outer) layer is typically nylon or polyester treated with a water-repellent.

This outer layer is bonded with an inner waterproof layer, a laminate or membrane. For example, you might have heard of PUL (Polyurethane Laminate) fabrics. They’re polyester laminated with Polyurethane, and you can use them to sew up diapers, reusable menstrual products, and period underwear—including the free Flo underwear pattern we have here!

If your waterproof breathable fabric has three layers, it might be backed with mesh, which feels more comfortable against your skin.

Here are some fabrics that are marketed as being waterproof:

-

Polyurethane-Coated Nylon: Polyurethane-coated nylon is made by coating a layer of nylon with Polyurethane for the waterproof barrier. It’s lightweight and flexible. -

Silnylon: Silnylon is a lightweight and waterproof fabric that's made from silicone-coated nylon. It's popular for outdoor gear, especially backpacks, and tents, as it's lightweight, strong, and water-resistant. -

Gore-Tex. Gore-Tex is a trademark name, much like other proprietary fabrics such as Tencel or Lycra. So while you can confidently shop the brand and you know what you’re going to get, there are other technical fabric manufacturers out there. Gore-Tex is appreciated for being lightweight, and you’ll find it advertised on much of the rain gear you buy in stores. You’ll find other waterproof, breathable fabrics that behave like Gore-Tex, such as Supplex, Ultrex, and other branded names.

What About Linings?

You don’t necessarily need a water-resistant lining for your project. If you want a little bit more moisture-wicking power, mesh was a clear winner for Seattle Fabrics—especially micro mesh. You could also use non-coated nylon, acetate linings, or even just something slippery from your stash, like rayon bemberg or voile. The more slippery your lining, the easier it will be to get your jacket on and off.

Depending on your project, you might not even need to line your jacket. Many 3-ply waterproof fabrics and softshell fabrics come with a comfortable layer on the inside that you can wear against your skin.

Waterproof Notions

Along with specialty fabrics, you’ll also need some specialty notions.

-

Wonder clips. Any hole you make in your fabric is permanent, so use clips instead of pins. -

Teflon sheet. Use this to protect your iron while you seam seal. You can use a tightly-woven press cloth on either side of your project in a pinch. -

Sharp needles. Microtex needles work well for many technical fabrics. Go with the thinnest needle you can use for your fabric to make smaller holes. It really helps to test your stitches on a swatch to ensure the needle can puncture many layers. -

Polyester thread. Polyester thread will last longer than cotton thread. You can optionally find UV-protected polyester thread, which is suited for outdoor waterproofing projects.

-

Water-resistant zippers. These coil zippers are treated with a DWR coating and designed to encourage droplets to bead on the tape, with only a .5mm space for water to seep through. You can even find water-resistant zipper pulls and cords. Here are some zippers from Seattle Fabrics. -

Sew-in interfacing. Your fabric might melt with fusible interfacing. If you do use fusible interfacing, test on a swatch first. -

Walking foot: Slippery fabrics might benefit from some dual-feed to evenly grip the layers of fabric. You can also use tissue paper with your regular foot. -

Teflon foot: Tacky, waxy fabrics might benefit from a Teflon foot to glide over layers of fabric. -

Tailor’s clapper: Waxed canvas and oilskin should not be ironed (except possibly on very low heat with a nice press cloth), so you need to finger press. A clapper can help you press seams into shape.

Sewing a Rain Jacket

You should follow your pattern’s instructions to sew up your rain jacket, but here are some tricks to help it all come together easily.

Cutting Your Fabric

- The first thing you can do when making your rain jacket is cut single layer. These fabrics are slippery!

- Your favorite fabric marking tool might not stick to waterproof fabrics. If you are lining your jacket, you can use a ballpoint pen to mark the wrong side of your shell.

Pressing

- There is no one-size-fits-all rule for pressing technical fabrics, as they all can withstand various temperatures.

- Test your fabric swatches, and use a press cloth on both sides of your swatch.

- Waxed canvas and oilskin should not be ironed or it will discolor and possibly melt. If you absolutely need to press, use low to medium heat and a press cloth. Or, you can use a tailor's clapper to help press.

Sewing Seams

-

Flat-felled seams provide some extra water resistence. - You might find it helpful to lengthen your stitch, even for your construction stitches. If you are worried you won’t remember to switch your stitch length back and forth between seams and topstitching, pick a length between, like 3 mm. Your stitches will be tight enough for construction but also look nice for topstitching.

- Usually we recommend using 3 rows of basting stitches. But waterproof fabrics aren’t the easiest to ease. So in this case, just 2 rows will be fine.

Seam Sealant Adhesive

Seam sealing tape or glue will close up any holes you poke in your fabric while sewing. If your fabric can’t be pressed, try using the liquid adhesive.

Brush it along your seams and wait for it to dry. Drying can take a few hours, so you can sew your seams in steps, apply the glue, and then continue construction when the garment is dry. Or, you can complete the entire shell and seal all seams at once.

Seam Sealer Tape

Your priority is to avoid melting anything except the glue on your seam sealing tape. Test on a swatch at various levels of heat. A polyester or medium-low heat worked for all the swatches we tested without melting the fabric.

To use seam sealing tape, cut a length as long as your seam. Lay the tape over the seam, covering your seam allowance, so it creates a complete seal. Using a press cloth or Teflon sheet on both sides of your fabric (unlike what’s in these pictures), press for 10 seconds, as you would interfacing. If your seam sealant has not melted yet, let your fabric cool and then press for another 10 seconds.

Here are some tips for sealing seams.

- Read your pattern a few times to know how it’s constructed. You’ll need to seal each seam after you sew it.

- If you must, choose which seams to seal. Your shoulder seams, hood, and pockets might be more important than your hem.

- Watch your seam allowance if you are topstitching any seams down before sealing them. Make sure your seam allowance isn’t wider than your seam tape. If it is, you might want to trim it.

- Trim the ends of your tape at some of your intersecting seams to avoid multiple layers of tape.

- For long seams, iron the tape starting at the center of the seam and then moving out to each end. This helps you avoid puckering.

- If you aren’t using a water-resistant zipper, you can seam seal the zipper tape once your zipper is inserted.

- Proceed with caution. Once it’s fused, even your seam ripper can’t help you. It’s done. Think twice. Fuse once.

- If you are sewing a lining, you might seam seal your entire garment and then poke new holes when you attach the lining. You can use bartacks to tack your lining at strategic points.

Caring for a Rain Jacket

It might sound counter-intuitive, but you do want to wash your rain gear if your fabric allows it. Rain jackets get oily and dirty, and by regularly cleaning them, the DWR can do its job.

Check your individual fabric’s care recommendations, but you can use technical cleansers specifically designed for waterproof fabric. Here is one from Nikwax.

Waxed canvas and oilskin shouldn’t be put into a machine with warm water, so spot cleaning is best. Otter Wax has a wax spot cleaner, but you can also use cold water and a cloth.

Avoid fabric softeners, bleach, or dry cleaning, as you don’t know how these will interact with the DWR. In general, you can let your jacket air dry.

Not sure if your jacket is still resisting water? Get a spray bottle and test! If your fabric originally turned the water into little beads that rolled off, and now it’s not, then it’s time for another layer of DWR or wax.